The 1991 season was one of the most entertaining of all time, because Rainey and Schwantz were spectacular to behold on Dunlop tyres, which allowed them to spin the rear tyre and execute lurid slides. Dunlop won 12 of the 15 races, with Rainey, Schwantz and Rainey’s rookie John Kocinski.

Those lurid slides relate to the words of Pecco Bagnaia’s crew chief Cristian Gabarrini, who a few weeks ago stated in this blog, “The physical limit of the bike is one thing; the mental limit of the rider is another – the physical limit can only make tenths if the rider is mentally ready to use it”.

Michelin slicks of that era gave more ultimate grip, but the grip the Dunlops gave was easier to use. In other words, physical and mental limits.

So even though you had less grip with the Dunlops, you were able to ride faster. Before you reached the Dunlop rear’s ultimate limit the tyre started to slide, so you could feel exactly what it was doing. Thanks to that you were confident enough to use all of its grip, to go to the absolute physical limit of the tyre, without fear of disaster.

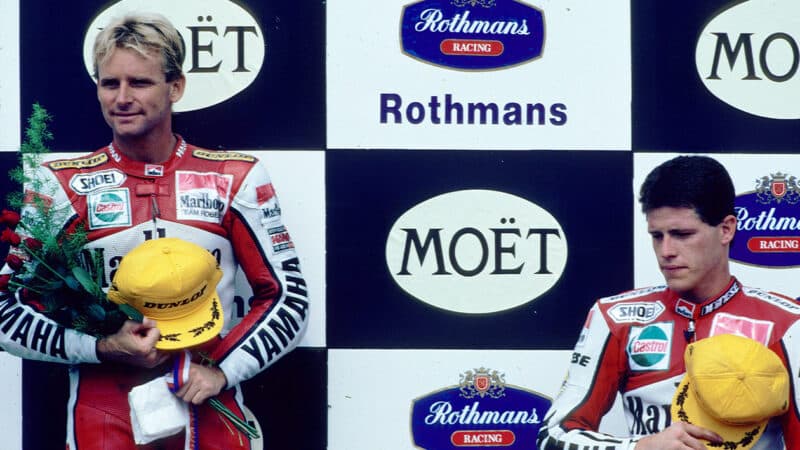

Rainey (left) and rookie team-mate John Kocinski in 1991 – Rainey won four GPs that year, while Kocinski took one victory

Yamaha

Meanwhile the Michelins gave more grip, but they didn’t have that early warning system – motorcycle racing’s air-raid siren – that told you that you were entering the danger zone.

Instead you got grip, grip, more grip and more grip. And then nothing. All of a sudden you were past the absolute physical limit of the tyre and usually the first thing you knew about it was the tyre losing grip, the bike snapping sideways and then launching you to the moon as the tyre gripped again, triggering the whiplash effect feared by every motorcycle racer of the last few decades: the highside.

That’s why most riders were scared of using the last few percent of the Michelins and that’s the difference between physical and mental limits – the gap between the two could be called user-friendliness, or to be specific, rider-friendliness.