When he got the square-four factory bike [the Yamaha 0W54] in 1981 he was getting plenty of works kit, so he was a lot happier, but we still made him bits like handlebars. He always like our handlebars for some reason.

When he got the V4 [the 0W61] before Silverstone in 1982 we were on holiday, so Spondon [Derby-based chassis makers] modified that frame for him. When I spoke to him about it later [after Sheene’s huge accident in practice, caused by colliding with a fallen bike at 160mph] he said I tried to f**kin’ phone you but there was no-one there. This was well before the days of answerphones and mobiles.

When he went back to Suzuki he was very unhappy with the RG they’d given him, so we built him a new frame. It wasn’t anything that special, just a large-diameter, thin-wall tubular steel frame. Barry didn’t like all the aluminium frames that were coming out at the time. Suzuki gave him a few aluminium jobs that Randy Mamola had used at HB Suzuki. It was when Suzuki got themselves into an awful mess – they made loads of different frames with all kinds of problems. Barry chose a few, tested them and said I don’t want any of them, I want Harris to build me a chassis.

Lester

That was the early days of aluminium frames. People were learning and they were just substituting steel tubes with aluminium tubes, which was ridiculous. We went for a tubular steel frame because we felt it would give the stiffness characteristics that he was used to. We’re still learning how much flex to put into a frame – it’s a black art because even now you get a frame working for one bloke and someone else wants something different.

At that time we were working a lot on rear suspension because suspension technology was a lot cruder. We fiddled around with loads of different rising-rate linkage systems and we did one for Barry that had a rocker at each end of the shock.

Steve

Barry wanted his bikes set up in a certain way. He didn’t care if the bike wobbled in a straight line, he just wanted it to turn quick and fall into corners. I think he probably had some fitness problems towards the end of his career which took it out of him, so he wanted the bike to turn almost on its own and that’s what we gave him.

Lester

He used to say, I don’t care how stable it is, that’s not an issue. For a lot of people it’s the opposite – as soon as the bike gets a bit wobbly they don’t want to ride it and who can blame them?

Lester

Everyone responds to a bit of praise and he would always get round to saying, if we could just alter this and just do that…

Steve

Yes, he’d say, I’ve been thinking… That was always a warning, because when he’d been thinking we knew it was a load of work coming our way. We had to work 24/7. But because of the way he was with people, our blokes would’ve done anything for him. We’d tell them you’ve got to come in on Saturday and Sunday and work till 11 at night…

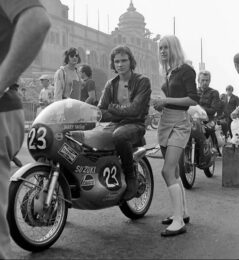

Sheene’s 1984 RG500 used a tubular-steel frame, when most riders were switching to aluminium chassis

John Keeble/Getty Images

Lester

And they’d say, “We’re coming in anyway, because we’ve got to get it finished”. There was no question of anyone going home or going down the pub. It was, “We’re doing this for Barry and it’s got to be done”.

Steve

The thing I remember about him more than anything else was the way he could manage people with his cockney whizz-kid way. “What ho, mate”, and all that. People loved it.

“Everything was a competition. If he was here now, he’d say, ‘I bet I can drink more cups of tea than you’”

Barry opened a lot of doors for us. When he was on your side, whoever you were, that would benefit you because he understood the value of PR, because he’d done a good job on himself. He would make sure that everyone knew he was coming here for his bits and why.

When we built his first RG500 he rode it onto the stage at the BBC Sports Personality of the Year do. He said, “These guys Harris are just coming into GPs, watch what they do”, which was very nice of him.

Lester

Once the 1984 season started we didn’t change the RG chassis much. We went through the normal altering the handlebars and all that stuff, which was more like a ritual to him than anything else. He felt that if he had done that it’d be right.

Steve

That RG was a great little bike. I went to Assen with him in 1984 and he was having a fantastic ride, up with Eddie Lawson on the factory Yamaha and Randy Mamola on the factory Honda. He shouldn’t have had that bike as far up the order as he did, then it broke a con rod. That year we put the bike on a dyno. It gave 140 horsepower, about 20 less than the works bikes.

Lester

Barry was a top, top rider. When Roberts came along he eclipsed Barry, but prior to that he was as good at it got.

Steve

We were at the Silverstone international in the early 1970s, sitting on the grass inside Turn 1. Barry was racing his Suzuki 500 twin against Giacomo Agostini on the MV 500. He shouldn’t have won that but he did. There was a grudge match between them – he was riding up onto the paving stones at the edge of the track to get round Ago. We were thinking, he’s going to bin it, big style, but he didn’t. And he got the better of Ago.

Lester

It’s ever so difficult when you get to the superstars: how do you actually judge one against the other? For me, Roberts was one of the best and I’d put Barry knocking on the door, but not quite there.

Steve

I’d put him fourth on riding ability, but as a complete professional motorcycle racer I’d put him on top because he could use people and make things happen. If you ever talk to any of his team-mates they’ll tell you that whenever a box of new bits arrived Barry would open the boxes and say, “That lot’s mine and these two are yours”.

Lester

All top riders are merciless. They are selfish people; they have to be. When you hear people criticising riders for that it’s daft because that’s what makes a champion.