“When we first went to four-strokes we still did a lot of work on the engine, because they weren’t sealed back then,” says Forcada. “We worked on the RC211V’s cylinder head, valves and so on.

“At first there were zero electronic rider controls on the RC211V; nothing in 2002, then it started in 2003, when we started with ride-by-wire throttles. That was the biggest change because with a throttle cable you can’t really have any electronic controls, but as soon as we had ride-by-wire throttles we started with traction control.”

In 2006 Forcada moved from Pons’ team to LCR Honda, where he worked with MotoGP rookie Casey Stoner.

“Casey was such a talent. Even when the electronics weren’t perfect he could control the bike with the throttle and rear brake – he made his own TC with the rear brake!”

In 2008 another MotoGP rookie, Lorenzo, asked Forcada to be his crew chief in the factory Yamaha team and he’s worked with the company’s YZR-M1 ever since.

That year was the year of Yamaha’s comeback – Rossi winning the title for the first time since 2005 and Lorenzo winning his first race.

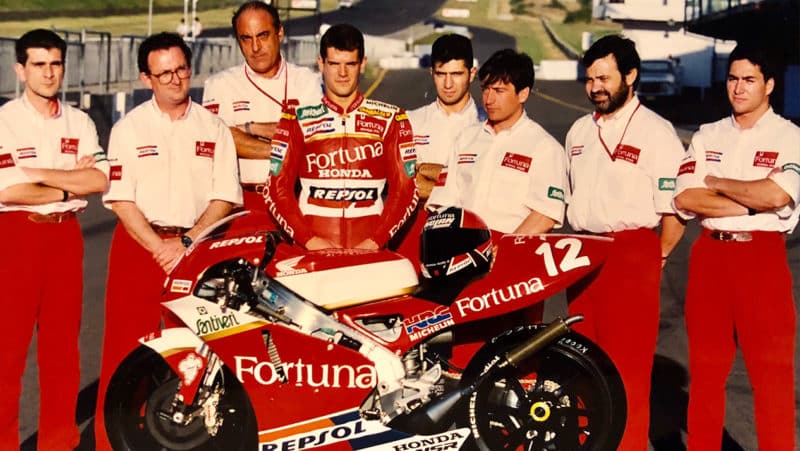

Forcada with Lorenzo and Stoner in 2008. Forcada was Stoner’s crew chief in 2006, the Australian’s rookie MotoGP season

Getty Images

“For me the big difference for Yamaha that year was their new electronics and Rossi switching to Bridgestone tyres. When Casey changed from Honda to Ducati in 2007 he said the biggest difference between the bikes was the tyres – he crashed a lot with the Michelin front.” (Honda used Michelin at that time, while Ducati used Bridgestone.)

Electronics have been the biggest area of MotoGP development over the last two decades. Burgess – perhaps the Australian Forcada – was never super-keen on high-tech rider controls.

“When electronics systems became complicated they became difficult in themselves,” Burgess told me a while back. “I didn’t mind the electronics per se, but you didn’t know if you could fix the problem with the rider or if the boffins could fix the problem with the electronics, so you often went into the race with this massive cloud over your head.”

“Check the data after a half-millimetre change and you can’t see anything, but the rider can feel it”

So what’s Forcada view on electronics?

“Masao Furusawa [the race chief who turned around Yamaha’s fortunes when Rossi arrived] hated electronics and computers!” Forcada laughs. “But now you have to work with electronics, otherwise it’s impossible to compete.

“But it’s a balance – how much you trust the rider and how much you trust the electronics. There are some crew chiefs who trust the data 100%. For me, no. Electronics are a big help, but many times I explain to the rider that when we change the settings we don’t change the bike, we change the feeling.

“If we change the set-up by raising the rear ride height by half a millimetre we don’t change the bike, we change the feeling, so the rider says, ‘Now I trust the bike and I can go!’. But half a millimetre is the rubber we use in a few laps, so it’s nothing! Feeling is everything! If you check the data after you make that half-millimetre change you can’t see anything, but the rider can feel it. Most riders are very sensitive – when they trust the bike they can be fast, when they don’t feel confident they are slower.”

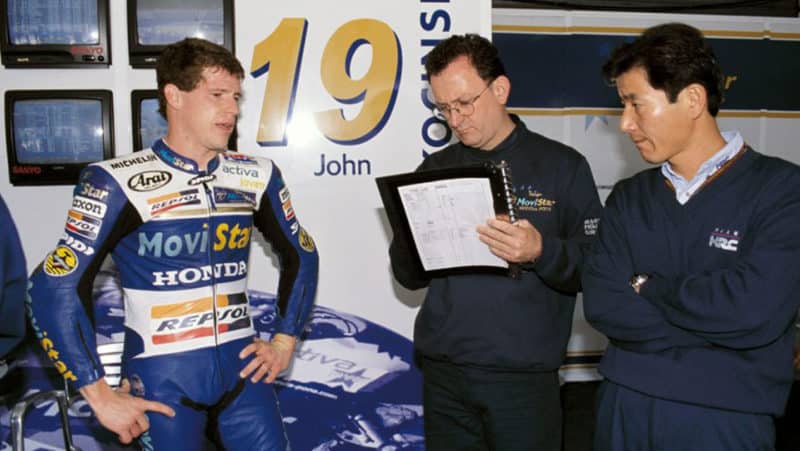

Forcada with Franky Morbidelli in 2020 – they won three races together that season

Getty Images

MotoGP’s most important change in the last half decade or so has been the switch from Bridgestone to Michelin tyres, which required a big redesign by all the manufacturers.

“We changed the bikes a lot, going from Bridgestone to Michelin. The Bridgestone front was so good, it basically worked by itself, so we put more weight on the rear to help the rear tyre. Now the tyres are more balanced, so we have to work with both tyres. We move the weight around, especially rider position, because the bike must be very balanced because the tyres are very balanced.

“You can work on chassis rigidity, on suspension and so on but the tyres are the only parts of the bike touching the ground, so the weight you put on each tyre is very important, plus the transfer of load between the tyres and the speed of that transfer. The Yamaha is a well-balanced bike, but the tyre balance depends on the rider. Jorge used less weight on the front because he carried so much speed into corners – he stressed the front tyre with his speed, not through braking.”

The big thing in MotoGP right now is the closeness of the competition, which is largely down to the tyres, especially Michelin’s front slick.

“The lap times are very close because we are at the tyre limit. If the tyre limit is here [he holds one hand up high] and you are here [he olds his other hand lower] you have room to improve. But once you arrive at the tyre limit you cannot go past that limit because the tyres are always the final limit

“Many years ago we would talk to the Michelin guy and more or less it was like this: put some air in the tyres and go! Now it’s become very, very, very critical because we are playing with a tenth or two-tenths of a second, so we have to go into the small details because when you are close to the tyre limit even a small change can make a difference. When you are playing with half a second or a second the tyres aren’t really critical.”

Forcada (far left) with current rider Andrea Dovizioso and crew

RNF Racing

Does chasing these tiny margins of improvement send Forcada crazy?

“A bit, yeah! In Formula 1 they also work a lot on tyre pressure, but when I talk to F1 engineers they say it’s easier for them because their tyre volumes are much bigger and they have only one brake disc per wheel, while we have two discs for the front wheel. They also have room for a heat deflector, to deflect hot air from the brake away from the wheel rim, and they change the deflector according to the track and the conditions. For us it’s more difficult.”

MotoGP’s issues with front tyre temperature and pressure are only likely to get worse in the near future, certainly until Michelin upgrades its front slick in 2024 or 2025.