And even then if you, like most people, live in a house or flat in a terraced street in a town or city, you’re still going to find it very difficult, if not impossible, to charge and that’s not likely to become any easier any time soon. I cannot find a single independent observer who reckons the charging point roll out is going at anything like the pace required to meet a 2030 deadline. And who’s going to buy an EV if they cannot even be sure they’ll be able to charge it, other than paying through the nose for it, for instance at a motorway services where electricity is already more expensive than petrol? And all this, remember, before the government figures out how it’s going to recoup the very many billions it currently relies upon from the tax on petrol and diesel cars.

Of course the choice is not simply between a pure petrol and diesel car on the one hand and a full EV on the other. There are hybrids too and they will be allowed to stay on sale until 2035. But plug-ins are extremely expensive, and inefficient too, requiring as they do two entirely separate power sources to be carted from one place to the next, usually with one doing all or almost all the work while the other is carried as near enough dead weight.

So the situation seems to me as follows: EVs work well, but primarily as second cars in households with off-street parking, and while the situation will likely improve over the next six years, come 2030 I expect this case largely to remain the same, while plug-ins are not the answer to anything, but an expensive stop gap solution for those wealthy enough to be able to afford them.

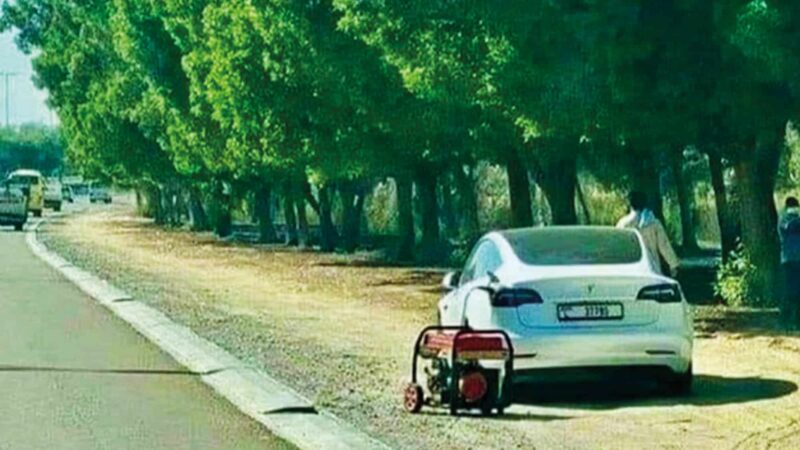

A petrol-powered charger for your electric car? This may be top of your Christmas gift list in 2030

What’s going to happen, then? I expect whichever set of glorious leaders are in office at the time will find a fig leaf which just about allows them to cover themselves and say they’re honouring the commitment. And it will be found deep within the undergrowth that is the definition of the word ‘hybrid’. For in truth, and technically speaking, even pure petrol cars are hybrids because they require battery power to get their engines turning.

It won’t be quite a cynical as that, but I’d not be surprised to see so-called ‘mild’ hybrids dodging the fall of the axe. These are cars with simple electric drives, usually running on a 48 volt system that provide a small amount of electrical energy to supplement the internal combustion engine. This is usually enough to allow the car to dispense with the need for a separate starter motor and alternator, offsetting the weight gain of the electric motor and small battery, but not nearly enough to allow the car to run on electricity alone. They provide a touch more torque at maximum load levels too, but in almost all scenarios owners won’t even know they’re there.

I can’t myself see any other way in which the government can appear to meet its commitment without new cars sales being decimated. Looked at like that, it becomes not so much a question of the right or wrong way to do it, but in reality probably the only way.