Bahrain F1 test: Norris quickest as Verstappen completes over 130 laps

The world champion replaced team-mate Piastri and topped the times for McLaren

Alex Albon finds himself in a race-winning car during his rookie season. Will he follow the path of Mike Hawthorn or Michael Andretti? Paul Fearnley looks at past precedents

Michael Andretti’s F1 career ended after ten grands prix Photo: Motorsport Images

No doubt Alex Albon was excited by news of his promotion to Red Bull Racing. But ought he be exercised about it, too?

For the next nine Grands Prix are likely the most important of what could be a very summery – or summary – Formula 1 career.

His vital signs so far have been good: innate speed wrapped in an aura of calm that has not precluded tigerish tendencies.

But to be handed a race-winning car so early in one’s F1 story can be double-edged. Just ask Dave Walker.

The Australian had won championships in Formula Ford and F3 – 25 wins from 32 starts in 1971 – before stepping up to the big leagues with Team Lotus.

A rare moment where Walker led his team-mate in the 1972 season Photo: Motorsport Images

But while his younger team-mate carved beautiful shapes in the fluid Lotus 72D, Walker just couldn’t hack it: zero points from 11 starts.

There were mitigating circumstances: lack of circuit knowledge and testing, plus older-spec engines. But nobody, least of all boss Colin Chapman, cared.

That Walker had, on his category debut in 1971, spun away a chance of points in the 4WD turbine Lotus 56B at a wet Zandvoort had been an ill omen.

For some drivers, F1 is just not meant to be. Walker was out.

That impressive team-mate might have shown more sympathy had he not been busy becoming the then youngest world champion.

Related content

Emerson Fittipaldi’s journey had included success in Formula Ford and F3, too, but it had been rather more immediate than Walker’s and his tracking somewhat faster as a result: from Wimbledon-based Cortina tuner and Jim Russell hopeful in February 1969 to F1 by the following July.

Unlike Walker, the Brazilian seemed born to it: he finished fourth in his second GP and won his fourth.

The latter was achieved at Watkins Glen in the aftermath of team leader Jochen Rindt’s fatal accident at Monza.

Third for Team Lotus on that uplifting Fall day in Upstate New York was Swede Reine Wisell, the occasion of his F1 debut.

Thus Team Lotus swept into 1971 on a wave of understandable emotion – and with a driver pairing with just seven GP starts behind it.

Wisell at the 1971 British Grand Prix Photo: Motorsport Images

They lost their way. Understandably.

Fittpaldi, his campaign interrupted by an injurious road accident, was retained thanks to three podium places in four races during the meat of the season.

Wisell, solid rather than spectacular – two fourths, one fifth and a sixth – was jettisoned for 1972 in favour of Walker, who in turn would be dumped to make room for Wisell’s compatriot, good mate and karting/F3 sparring partner Ronnie Peterson.

Albon, like Walker, is to be measured against a likely future world champion, a man who has made a team his own – should he want it – since winning on his debut for it in 2016.

A tough act to follow but it can be done.

Mike Hawthorn had just five GPs – in a Cooper-Bristol – to his name when he signed for Ferrari in 1953. Bucking the accusation of inconsistency often levelled at him, he finished all eight of that year’s world championship rounds and, at Reims, beat his unbeatable team leader Alberto Ascari – as well as Maserati’s Juan Fangio – to score a brilliant victory.

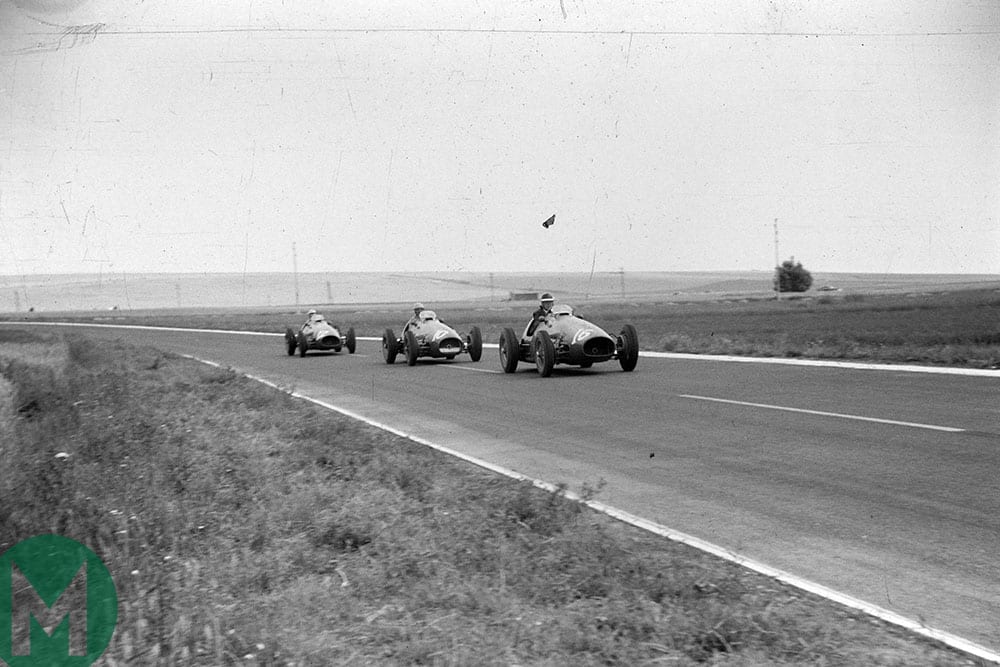

Mike Hawthorn leads Alberto Ascari and Luigi Villoresi in Reims Photo: Motorsport Images

Damon Hill had just two GP starts with the fag end of the once-glowing Brabham – and thousands of testing miles admittedly – under his belt when he was pitted against Alain Prost at Williams in 1993. He kept the three-time world champion honest and endured two near-misses – a blown engine and a blown tyre while leading at Silverstone and Hockenheim – before reeling off three consecutive victories in the season’s second half.

And right from the off, Lewis Hamilton so rattled Fernando Alonso at McLaren in 2007 that the two-time world champion threatened to rat on the team to the FIA.

Tony Brooks, John Surtees (while simultaneously engaged winning a brace of motorbike world titles for MV Agusta), David Coulthard, Froilán González, Dan Gurney (second, third and fourth in his second, third and fourth GPs, with Ferrari), Phil Hill, Jacky Ickx (until his Ferrari’s throttle stuck open and he fractured a leg at Canada’s St Jovite), Bruce McLaren, Jody Scheckter (Silverstone carambolage aside) and the Villeneuves, father and son, also took such golden F1 opportunities in their stride.

All will be well if Albon is of similar calibre.

If, however, he is ‘only’ as good as Michael Andretti, he might struggle.

The fanfare that met the Indycar star’s arrival in F1 in 1993 was swiftly drowned. Attempting to follow team leader Ayrton Senna’s Squeegee-d tracks through a Donington Park downpour, he collided with another and beached in the gravel.

Andretti struggled to escape Senna’s shadow Photo: Motorsport Images

Ten GPs later F1 was done with him – and he of it.

Wiser men pick their fights more carefully.

Mario Andretti rang Chapman only when he felt ready for F1 – and promptly put his Lotus 49B – “it felt like a toy” – on pole for the 1968 United States GP at Watkins Glen.

Team-mate Jackie Oliver, inexperienced and doomed to failure as the late Jim Clark’s more immediate ‘replacement’, failed to start the race after crashing in practice. A broken wheel the cause.

Though he would score his best result of the season at the next GP – third place in Mexico City – it was too late to save Oliver at Team Lotus.

Less dramatic, though perhaps more emphatic, was 1984 runaway British F3 champion Johnny Dumfries’ single season of F1 ‘alongside’ Senna at Team Lotus in 1986.

And then there’s Jos Verstappen.

Much was expected of the reigning German F3 champion when he filled in for and eventually replaced JJ Lehto at Benetton in 1994.

Verstappen struggled with a Benetton built for Schumacher Photo: Motorsport Images

It had by this time, however, become entirely Michael Schumacher’s team and a couple of third places in a car tailored to suit the German’s apparently impossible-to-replicate driving style was deemed insufficient and Verstappen was himself replaced for the final two rounds.

Those third places would remain the best results of a 107-start F1 career that Jos was never quite able to boss.

Albon, of course, is at the beck and call of Red Bull – though he has seen both sides of its scheme having been dropped after a disappointing Formula Renault Eurocup campaign in 2012.

But imagine if he had declined the offer, preferring instead to continue to learn his craft at Toro Rosso.

Just because that was never going to happen – he’s getting on a bit at 23 – doesn’t mean that that would have been so dumb.

Jackie Stewart, then the fresh prince of a new F3, could have joined his friend and mentor Jim Clark at Team Lotus in 1965. Though still green, he knew enough to know that he would have been on a hiding to nothing had he done so.

He joined less glamorous but more solid and dependable BRM instead.

Stewart (right) avoided the mistake of joining Clark (left) at Lotus in 1965 Photo: Motorsport Images

Avowedly very different times, but I would argue still that Stewart’s F1 career is a model of how it should be done.

And if Albon gives it his max in the next nine races, he strikes me as someone with similar attributes to the sage Scot.

We will know soon enough if I am wide – and by exactly how much in this unblinking, unforgiving data-driven world – of the mark in this regard.

The world champion replaced team-mate Piastri and topped the times for McLaren

Four-time world champion goes quickest as Bahrain's 2026 F1 test starts

Mercedes' F1 rivals are united in protesting its new power unit, as the series aims to stamp out "smart rule interpretation". But it won't be easy to resolve, explains Mark Hughes

Three days in Bahrain will provide crucial answers before F1's new era begins