“The whole Ferrari organisation went out to find these grilles, find where they came from and make them for their three cars. Then we put our three cars in the pit road and took all the grilles off the T-Car. Niki came down and said ‘You f**king bastards!’ They came down the pitroad and Ferrari had this shit all over their car – these grilles all over the radiators.

“He had to tear back and tell them to take them all off. Psychologically we had them on the back foot right from the start, there’s all this psychological warfare.”

The mind-games might well have been in vain, for the monsoon weather which rolled in on Sunday looked like putting the race in jeopardy. If the Grand Prix was cancelled, Lauda would be handed the World Championship.

The Grand Prix Drivers Association had been formed to have some influence on such matters, to stop the interests of teams, the governing body and sponsors taking precedence over drivers’ well being. Hunt and Lauda were both members and convened prior to the race start in an effort to have it stopped.

“They were adamant the race wasn’t going to be held. Bernie (Ecclestone, Brabham team boss) and I were in the race control tower trying to convince them to hold the race.” says Caldwell “And James kept on saying ‘No no, we’re not going to race’. I tried to explain to him that no race meant no World Championship. He replied “No, no, no, it’s totally unsuitable, we can’t race”.

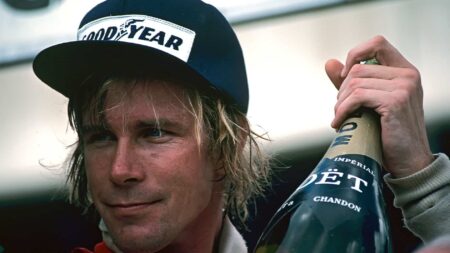

The waiting game: Hunt, Lauda and Peterson

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Caldwell resorted to more imaginative tactics to swing the mood towards starting the race.

“I was going down (to the pits) getting my car mechanics to start the engines every half an hour, which would make all the other teams start doing it – they didn’t know why. The engines were making this noise ‘woop, woop, woop’”.

The engineer then turned his attention to activating the spectators.

“I was trying to get some enthusiasm from the passive Japanese crowd, they’d been there for hours doing nothing. They weren’t even talking, just sitting in the rain – miserable.

“I said to our tyre man Lance Gibbs ‘Do you think you could get the crowd going?’ So he got up on the pitwall with his ACME Thunderer whistle, which had been given to the boys to use as a horn, for when they pushed the race cars around the paddock.

“He went ‘beep beep’ and hundreds of spectators did the same – got them doing a concert. We then did the business of slow clapping, when it gets to the end, people can’t keep up, they lose co-ordination and you get a huge noise.

“I went back to the tower and the geriatric Japanese officials and said, ‘Look, you’ve got a riot on your hands’ Bernie was there and he said ‘Yeah, you’ve gotta hold the race. Otherwise you’ll have trouble’. So they said ‘Ok we’ll have the race.’”

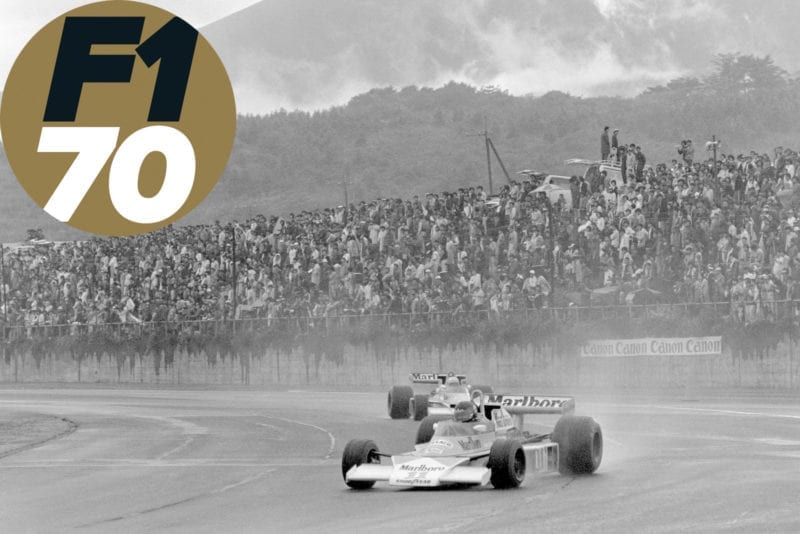

Patrick Depailler in the spray of race day

Grand Prix Photo

With the decision made, the cars finally lined up to start at 4pm. The deliberations had been going on so long that the light was now beginning to fade, reducing the limited visibility even further.

Hunt, starting in second, lined up next to poleman Mario Andretti on the grid. Lauda was just behind in third. As the flag fell, the Englishman got the jump on the Lotus driver to lead into the first corner.

By the end of the first lap, his gap to Andretti was 4sec. Hunt had charged round lap 1, but there was a soon warning of how treacherous the conditions were.

As the McLaren driver headed into T1 on lap 2, his M23 suffered a vicious twitch, almost pitching him into the wall. Hunt just about managed to maintain control, before cautiously carrying on.

After just 1 lap, Lauda had seen enough. Deeming the conditions too dangerous, and having already nearly lost his life at Nürburgring that year, the Austrian decided it simply wasn’t worth carrying on. He pulled his Ferrari into the pits and walked away from the 1976 World Championship.

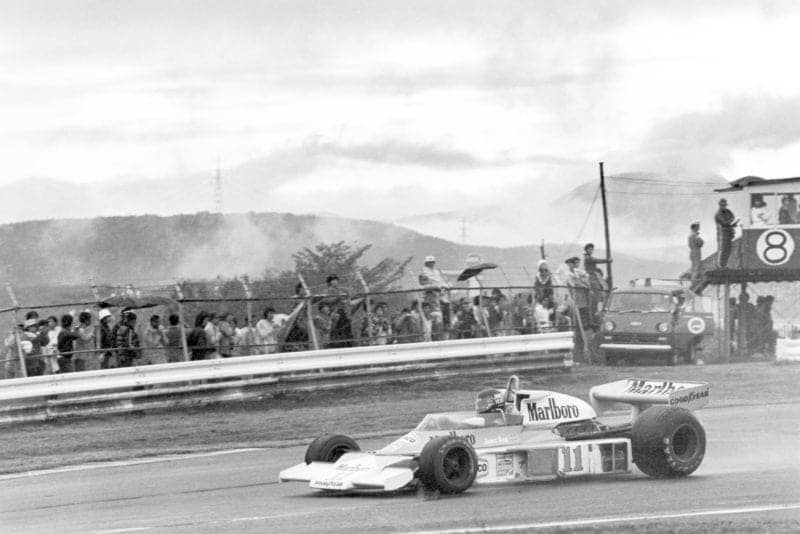

Lauda leaves the Grand Prix – and the championship race

Grand Prix Photo

With Lauda out the race, Hunt’s task was now a little more straightforward. He simply had to finish third, and the title was his.

The McLaren driver pressed on and by lap 10 his lead had doubled to over 8sec. Meanwhile, interesting movements were afoot further back in the pack.

Local hero Kazuyoshi Hoshino, driving a privately-entered Tyrrell 007, had made his up to third, from 21st on the grid!

More worrying for Hunt was that March’s Vittorio Brambilla had overtaken Andretti and was beginning to hunt him down. By lap 20, Brambilla had closed right up behind the Hunt.

On the next lap, the March driver decided to go for it. Brambilla, known for an erratic driving style, conformed to type on this occasion by inadvertently out-braking himself as he dived down the inside of the McLaren.

Hunt had been wary of Brambilla and was monitoring the situation constantly. In a moment of brilliant anticipation, he allowed the March to spin in front of him, performing the cutback and before carrying on as if almost nothing had happened.

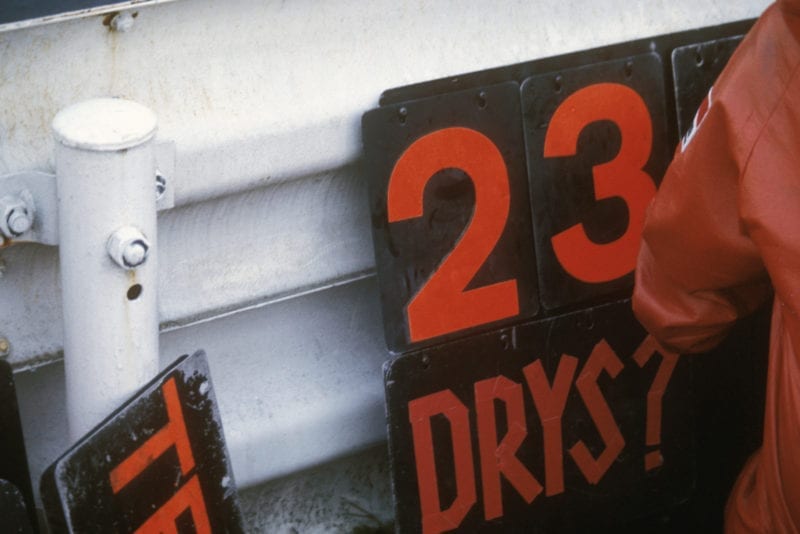

Hunt drives away from the spinning Brambilla

Grand Prix Photo

Brambilla dropped to fourth, the danger to Hunt being over for now. Andretti at this point was gradually dropping back through the pack. It was Hunt’s team-mate Jochen Mass who was behind him now, with a McLaren 1-2 now looking very much on the cards.

Seeking to control the race from here on in, the team’s new concern was the drying line which was now appearing on the track. Caldwell put out a pit board sign telling his drivers to cool their wet weather tyres – this was done by searching for wet sections of the track, the water preventing the rubber from overheating.