In ‘66, Brabham’s Repco engine had been the power unit to have. With Monza being a power circuit, Clark’s prime grid position confirmed that, on pace at least, the DFV engine was looking a wise choice for’67 and beyond.

The entry that day was a roll call of grand prix greats. Along with Clark and Brabham, Bruce McLaren (McLaren-BRM), Chris Amon (Ferrari), Dan Gurney (Eagle-Weslake), Denny Hulme (Brabham-Repco), Jackie Setwart (BRM), Graham Hill (Lotus), John Surtees (Honda) and Jochen Rindt (Cooper-Maserati) also lined up. Opponents not to be underestimated.

The start procedure became slightly confused. Normal protocol was to roll the cars forward from a “dummy grid” once an initial flag was waved, then wait for a second flag to signify the start of the race proper.

In his race report, Jenks remarked “there was a tension in the air that said ‘this is going to be a fantastic start’”. The tension proved to be a bit much for some on that day at Monza, as experience and composure seemed to go out the window.

Clark was typically unruffled by early setbacks. On lap two he passed both Hill and Brabham, then set his sights on the lead.

As the first flag fell, Jack Brabham decided to throw caution to the wind. The Australian simply put his foot down and went for it.

In a flash the rest of the grid followed suit, blasting off before the start signal was actually given. The only driver who didn’t, was Jim Clark.

Not having his car at peak revs for what was supposed to be a short trundle to the real grid, the Scot found himself swamped by his competitors. He collected himself and regained some ground as they sped round the circuit. By the time things shook out on the first lap, he was fourth.

Brabham had hared off at the start but Dan Gurney hunted him down and took the lead halfway through lap one. Graham Hill was close behind in third.

Clark was typically unruffled by early setbacks. On lap two he passed both Hill and Brabham, then set his sights on the lead.

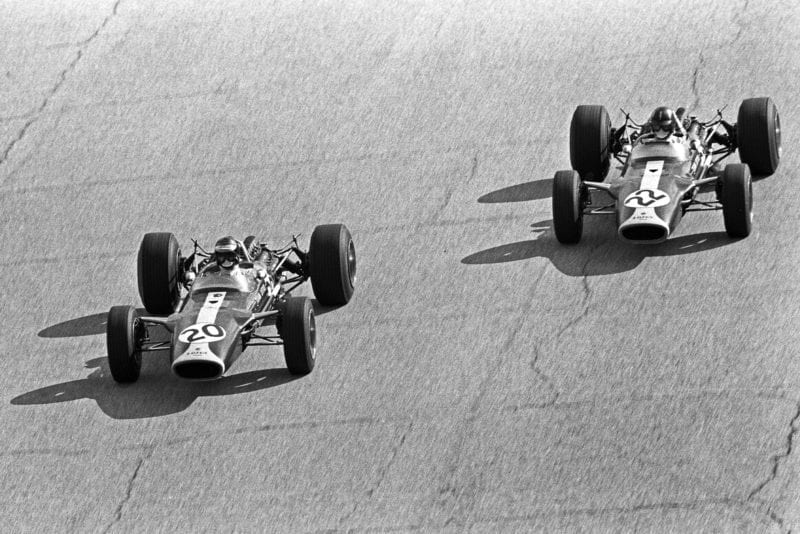

Jack Brabham speeds into the lead as Jim Clark slips back from pole

Getty Images

On the next lap Clark took Gurney. In the space of three laps he’d already gone from pole, to near disaster, to retaking the lead once again.

For one lap Gurney kept up with the Scot, his Weslake engine not short on power. However the all-out blast at the “Temple of Speed” proved too much for the American’s power unit and it failed on lap four.

Clark’s mastery behind the wheel combined with the superiority of his car and engine made it look like things might well be straightforward from here on in. He had a clear road ahead of him on a sunny day in Monza.

It was not to be.

Many would have considered the Lotus driver’s race dead in the water. The Scot had other ideas.

On lap 11, Clark’s Lotus 49 began to develop some unusual handling characteristics. The gap he had built over the chasing pack began to shrink.

As was usual for Clark, instead of pitting, he decided to adjust his driving style to the problem.

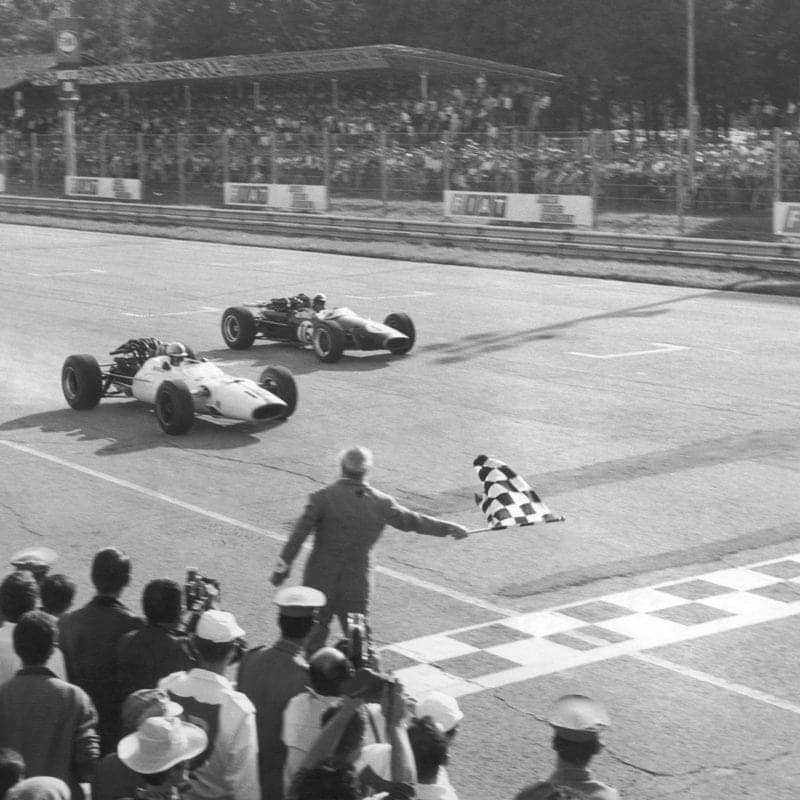

Hulme, who had moved into second, then passed the stricken Clark on lap 10. Clark, despite an ailing car, managed to squeeze back in front on the next lap, but it became apparent he was fighting a losing battle.

Brabham soon closed in also, nipping inside Clark’s Lotus at the Parabolica. As he did so, the Australian pointed to the Scot’s right-rear wheel, alerting him to a puncture.