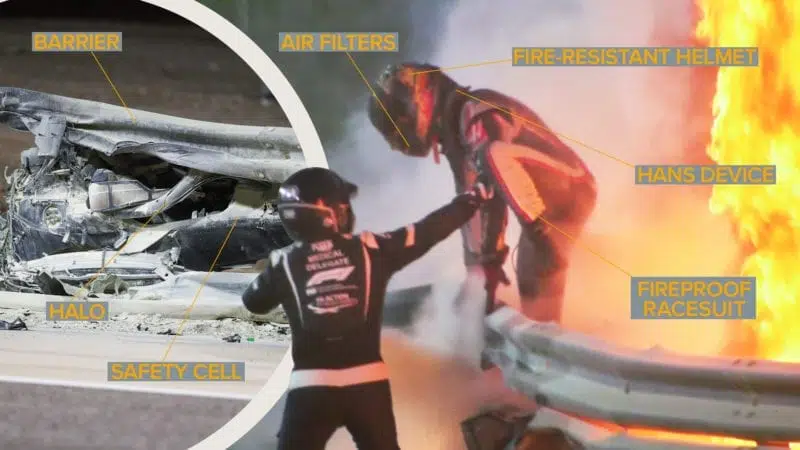

That he was conscious to process those thoughts; in a fit state to walk away; and could withstand 28 seconds of intense flames is down to a number of safety features that prevented what is likely to have been a tragedy, just a few years ago.

Some of the safety standards that Grosjean benefitted from have been in place for just a few months. Others are in the process of being improved further.

We’ve summarised several of the key features below, with links to read in more detail about how each one contributed to the joyous images of Grosjean returning to the Bahrain circuit, just days after his crash.

Carbon fibre safety cell

Grosjean’s story of survival begins with the safety cell that surrounded him: the cocoon of carbon fibre and Kevlar that’s extensively tested to ensure that it can withstand collisions such as the 53g impact that Grosjean sustained.

Pre-season crash tests include hurling the front of cars towards a solid wall to ensure that they protect the occupant’s limbs; and that the fuel cell remains intact.

Another key measure is the energy transferred to the driver. In conjunction with the nose — a sacrificial crash structure that’s designed to absorb energy by crumpling — the safety cell must limit the g-force that an occupant is exposed to.