Some argue that Aprilia’s first and biggest mistake with the Cube was hiring Formula 1 engineering legends Cosworth to design the engine: which was basically three cylinders off a ten-cylinder three-litre F1 engine. F1 engines are designed for peak power, because F1 cars have loads of grip, while MotoGP engines should be designed for part-throttle power, because they have much less grip.

The Cube had a super-light F1-style crankshaft, so it picked up revs so fast that neither the rider nor the rear tyre could keep up.

“It wanted to kill you everywhere,” says Jeremy McWilliams who raced the Cube in 2004. “It made lots of horsepower but in all the wrong places. I think it broke every one of my ribs twice that year,

“The engine had a very light crankshaft, so it had too little inertia, so as soon as you opened the throttle the rear tyre would spin. We were always asking for more inertia, but they said there was no room in the engine.

“It also had this really weird torque curve, so the engineers tried to fill in the holes in the curve with clever fuel and torque maps. It started making torque at around 9000rpm, then it dropped away and then there was a really sharp torque peak at 12,500, which sent the bike sideways and fired you on your nose.”

A wide-eyed Regis Laconi and the original RS Cube during the 2002 Italian GP at Mugello, where the machine became the first MotoGP bike to break the 200mph barrier

Aprilia

Aprilia therefore almost completely redesigned the Cube for the 2005 season. Engineers retained the inline triple layout, but changed the cylinder angle, increased crankshaft inertia and generally made it more of a MotoGP engine than an F1 engine. The original Cube engine was so F1 that the engine and gearbox were essentially separate units, something which motorcycling had given up many decades earlier.

“We kept the pneumatic valves, and the cylinder head and the injection system were similar, but we changed the layout,” says Germano Bergamo, Aprilia’s racing vehicle design manager, who has been with the company since before it won its first world title in 1992.

“We made the new engine a single unit, integrating more parts. For example, typically in F1 the scavenge pump is mounted outside the engine and Cosworth used this system when they designed our engine. We moved the pump inside and also fitted the auxiliary systems like the water pump, fuel pump and generator on the same axis behind the cylinders.

“We also moved the countershaft from below the crankshaft to above the engine. All these changes made the engine shorter and more compact. For example, without the scavenge pump mounted outside the front of the engine we could put the exhausts closer to the engine, leaving more room for the radiator and oil cooler.”

The more compact engine was housed in a completely new chassis, CNC-machined from solid billets of aluminium alloy. This was a new and much improved way of fabrication, because the various sections don’t need to be heated and bent into shape, which had been the traditional method for decades, causing all kinds of inconsistencies, so no two chassis are ever quite the same.

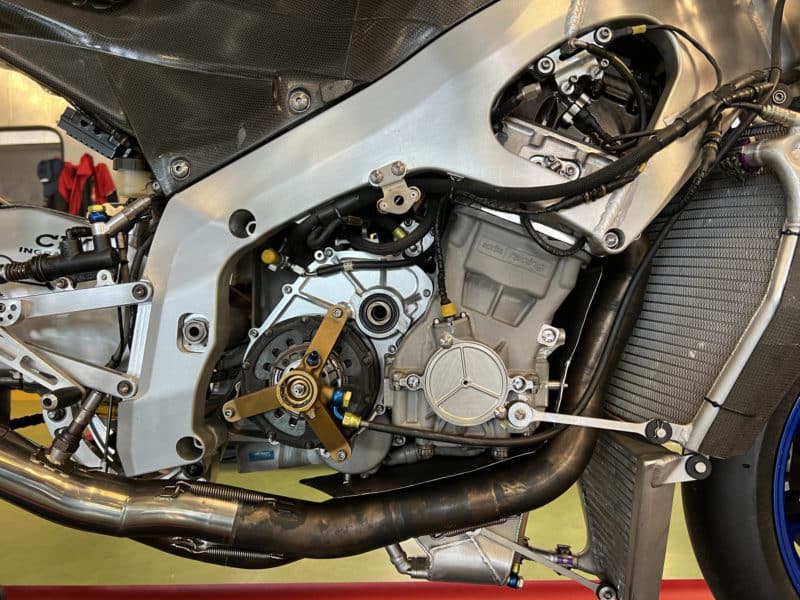

The first RS Cube engine, designed by Cosworth. Note how the engine and gearbox units are separate, like a Formula 1 engine. This made the engine too long, which compromised chassis design

Oxley

The shorter engine also allowed a longer swingarm. “You get a bigger lever with a longer swingarm,” adds Bergamo. “So this is better for traction and chain force.”

Aprilia wasn’t above copying Honda when it came to the detail design of the swingarm. After all, Honda’s RC211V was the best motorcycle in MotoGP at the time.

“We studied the linkage used by Honda,” Bergamo continues. “They fitted the shock directly to the swingarm, so we used this idea to reduce the chatter that the rear wheel can transmit to chassis.”

“We had ride-by-wire throttle but it was opened and closed by cable, to give riders the sensation they were used to”

McWilliams and veteran Aprilia test rider Marcellino Lucchi (who beat Valentino Rossi to win the 1998 Italian 250cc GP) had their first runs aboard the new Cube in late 2004, but the bike went largely unnoticed because everyone was much more interested in the latest RC211V, Ducati Desmosedici and Yamaha YZR-M1.

Bergamo was confident that the new Cube would get Aprilia closer to the front of MotoGP than the original, which had never bettered the sixth place Edwards achieved at the 2003 season-opening Japanese GP.

“I think results would’ve been better in 2005,” he says. “The overall conception of the machine was improved and we had around 240 horsepower [at 18,000rpm], about ten more than the previous bike.

“The biggest problem was managing the engine with the electronics. This was absolutely the beginning of the electronics that MotoGP has now. We had some ideas about traction control and other electronic controls, but we didn’t have the experience to manage so much horsepower. We wrote our own software for TC, anti-wheelie, engine-braking, launch control and anti-jerk. It was the beginning, so it was basic stuff, nothing like what we have now.

The more compact second-generation Cube engine, plus chassis machined from solid aluminium billet

Oxley

“Although we had ride-by-wire throttle, the actual throttle was opened and closed by cable, to give riders the sensation they were more used to. All the electronic controls were based on different gas maps, not by adjusting the injection or timing. Plus, of course, we didn’t have any gyros or accelerometers, so it was only the beginning of this work.”

And then the end…

Piaggio – already owners of Vespa, Derbi and Gilera – had bought Aprilia (and Moto Guzzi) in August 2004. In January 2005 the company decided to axe the Cube project.