When Moss, on a measured half-throttle yet still pulling 150mph-plus along the Mulsanne Straight, breezed past the Talbot-Lago – a GP car in two-seater, cycle-winged disguise – of José Froilán González on the opening lap, the template of that groundbreaking Le Mans was set.

The beefy Argentine promptly scrabbled back past under braking – the Jag was still on drums, too, in 1951 – only for Moss, grinning inwardly, to breeze by once again on the run to Arnage.

Five laps of this taunting and the Talbot’s goose and much else were pretty much cooked.

Moss led by a lap after two hours and headed a Jaguar 1-2-3 after four.

It was too good to be true.

A copper oil pipe in the sump succumbed to vibration and bearings ran dry after eight hours. The same problem had sidelined the sister car of Clemente Biondetti/Leslie Johnson four hours earlier.

Walker and Whitehead took the honours for Jaguar after Moss’s retirement

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

That night was wet and miserable – and the Jaguar’s headlights were one of its lowlights – yet the remaining C-type greeted the dawn with an eight-lap lead.

Peters Whitehead and Walker – Yorkshiremen born fewer than 10 miles apart, in Menston and Huby respectively – had continued to wear down opposition that included a Talbot co-driven by Juan Manuel Fangio and heroic 1950 winner Louis Rosier – plus nine Ferraris and a fleet of Chrysler V8-engined Cunninghams.

The latter’s prodigiously well-stocked transatlantic operation had served to emphasise the necessary Austerity of Jaguar’s – and should highlight the difficulties facing over-reaching, underfunded British Racing Motors in its bespoke endeavours elsewhere.

Raymond Mays – surely the prototypical sponsorship-finder – had worked wonders to persuade a ruminative British industry that his GP car was worth investing in.

Oddly he showed simultaneously that it could be done and how not to do it. Valuable lessons both.

He had also spotted Moss’s potential – honed in svelte Jaguars, spindly Formula 3 Kiefts and up-and-at-’em Formula 2 HWMs – and invited him to a test.

Mays got more than he bargained for.

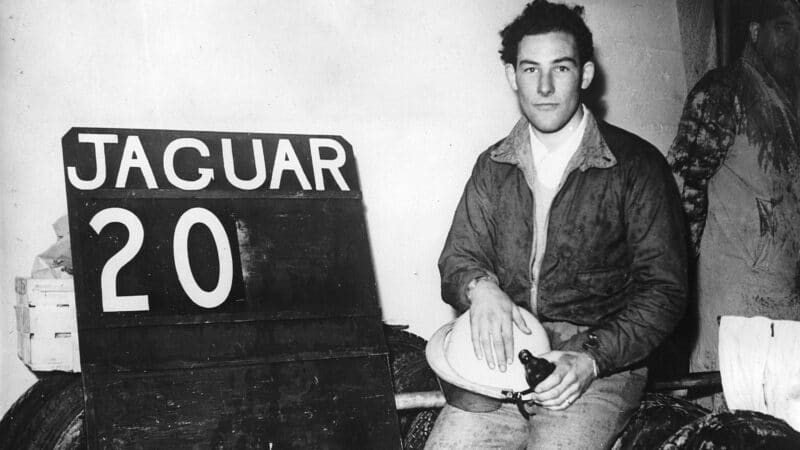

The youthful Moss, here at Le Mans in ’51, immediately identified the BRM’s flaws

ISC via Getty Images

Moss, though of course drawn to the V16’s siren’s song, was not blind to the car’s shortcomings. Sadly his complaints – peaky power, spooky steering, cramped cockpit – fell on deaf ears.

Invited to commit them to paper after a long and frustrating test at Monza – BRM’s withdrawal from the Italian GP had been yet another embarrassment – it was too detailed for some to stomach; few suggestions were acted upon.

He was still just ‘The Boy’ in some eyes.

Walker, 17 years Moss’s senior and reckoned by Jaguar team manager ‘Lofty’ England to be Moss’s equal in terms of speed if not application, was rather more sanguine.

Three weeks after winning at Le Mans by nine laps – ahead of the nearest Talbot – Walker was selected alongside Reg Parnell to give the BRM its GP debut at Silverstone.

He finished seventh to Parnell’s fifth, six laps in arrears and in pain, covered by oil and cooked by exhausts.

More than 24 Hours packed into 84 laps.

Walker drove the BRM V16 to a painful 7th place at the 1951 British GP

GP Library via Getty Images

Prior to the GP he had helped Whitehead demonstrate their Le Mans winner, with Moss – still without an F1 drive but a comfortable winner of a support race in the futuristic Kieft – perched perkily on its tail.

Motor Sport, still hopeful, intoned: “May the BRM follow in its noble wheel tracks…”

Moss would join Walker in racing the V16 just once – his underwhelming experience at Dundrod’s Ulster Trophy in June 1952 proving less physically painful but perhaps more mentally scarring.

He again put pen to paper, this time to say, ‘Thanks, but no thanks.’

Dundrod drive in the BRM was enough for Moss

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

He would spend the rest of that season and the whole of the next on a fruitless quest to find a British-made GP winner.

Being ahead of your time can be a double-edged sword.