To this, Balcaen adds one additional factor – the pioneering work of his friend Robert “Pete” Petersen, who founded Hot Rod in 1948 and established the template for the American car-enthusiast magazines, which served as both news services and repositories of how-to knowledge. “The magazines were like the internet,” Balcaen says. “They were the vehicle that reached people. If it hadn’t been for Petersen, the industry wouldn’t have gotten off the ground.”

Balcaen himself absorbed a lot of his early knowledge from reading Hot Rod, which inspired him to start street racing his mother’s Chevy when he was 15. This led to a gig driving a nitro-powered “digger” – a willowy, front-engine, purpose-built dragster – for drag racing legend Ed Donovan. Eventually, Balcaen would build a Top Fuel dragster of his own – dubbed the Bantamweight Bomb because of the drilled chassis rails – and win races everywhere from Lion’s Drag Strip south of L.A. to Half Moon Bay near San Francisco.

But there was no money in drag racing at the time, so Balcaen found a day job as a mechanic at the Beverly Hills sports car shop run by Warren Olson. Besides serving as the local Cooper distributor, Olson catered to a celebrity clientele. One of his best customers was a rich, young wannabe racer named Lance Reventlow, who was the heir to the Woolworth fortune. When he was 19, Balcaen restored Reventlow’s Bugatti Type 57 Stelvio convertible.

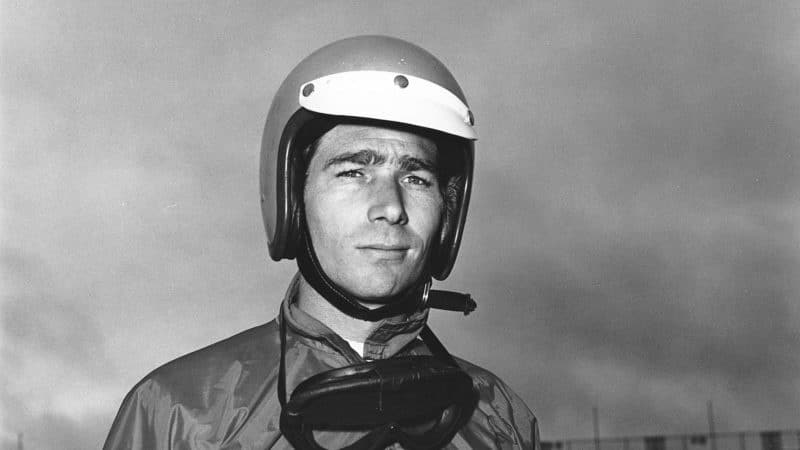

Balcaen credits Robert ‘Pete’ Petersen – pictured on left with Dan Gurney – as crucial for spreading the drag racing good word by founding ‘Hot Rod’ magazine

Eric Rickman/Enthusiast Network via Getty Images

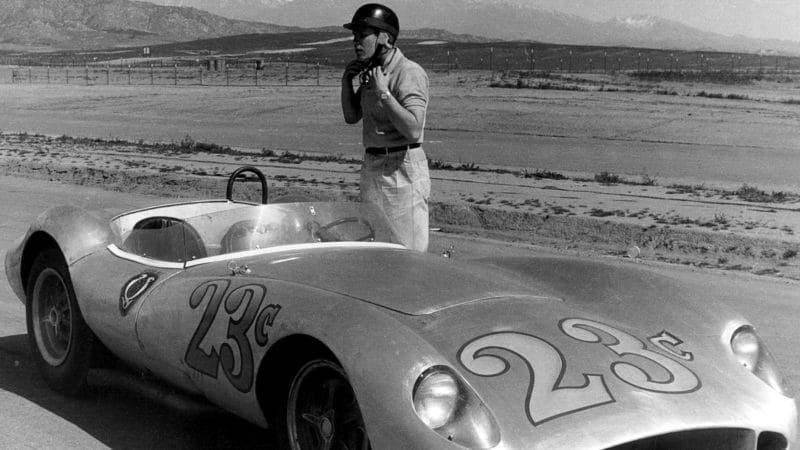

Through Reventlow’s friend Bruce Kessler, Balcaen met Carroll Shelby, who hired him to race-prep and support the sports cars being campaigned by another lanky Texan, Jim Hall, a recent Caltech graduate who was moving up the road-racing ranks. At the time, Hall was running a 2.0-litre Maserati and a Ferrari 750 Monza, with a Lotus Eleven and a Lister-Chevrolet on the way. Balcaen enjoyed his time with Hall but hated working out of a shop in Dallas. “It was hotter than hell in the summer and colder than hell in the winter,” he says.