Stropus followed a circuitous path to motorsports fame. Born in Lithuania, she emigrated to the United States as a displaced person in 1949. A childhood interest in cars was rekindled by a boyfriend who owned a Jaguar XK120 and a ’57 Chevy. Although she autocrossed a bit early on, she quickly found a niche in timing and scoring.

This was long before cars were equipped with transponders and sanctioning bodies scored races electronically. Hell, this was before digital stopwatches, for God’s sake. Races were timed and scored by hand, which worked fine. But lap times weren’t available until sessions were over, and there were sometimes disputes over finishing positions. So most teams deputized a member of the crew to work a stopwatch.

In 1967, Stropus traveled to Marlboro Speedway to time a friend. At a cocktail party after the race, she met Bud Moore and Fran Hernandez, who ran the Mercury Cougar Trans-Am programme. They offered her $25 to stick around an extra day to work the Trans-Am race, which she did, sitting on a toolbox with ramps over her head because there was a chance of rain. The next week, Moore and Hernandez asked her to fly out to California for the race at Modesto. “They were paying all my expenses, not just $25,” Stropus says. “I said, ‘Sure, I can do that.’ I was so excited that I went out and got a whole new wardrobe.”

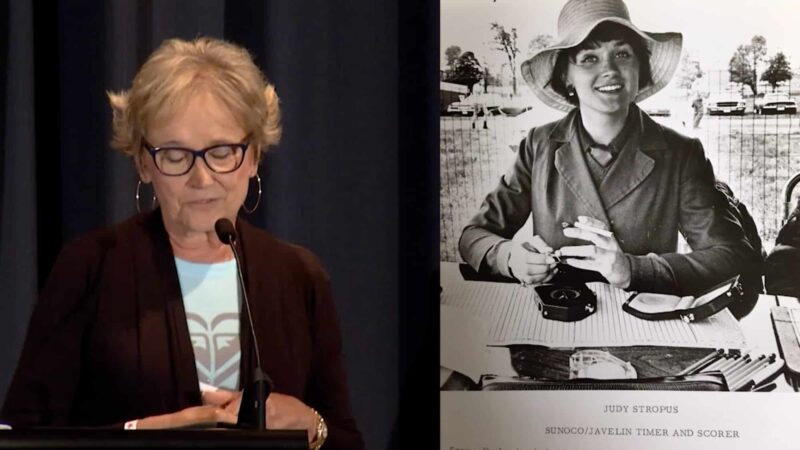

When Moore moved on to Ford Mustangs, Stropus switched allegiance to the AMC Javelin team. At one race, she recalls, “Roger Penske walks by me and says, ‘Why aren’t you working for me?’ and keeps on walking.” Before long, she was timing Can-Am for Penske. Eventually, she quit her weekday gig as a legal secretary and starting doing timing and PR on a full-time basis.

Stropus soon moved on to working for Penske in Can-Am – pictured here is George Follmer

John Lamm/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images

Stropus worked with a single Heuer stopwatch. The fundamental technique involved subtracting the current elapsed time from the previous elapsed time to calculate a lap time. This required speed and accuracy but it wasn’t super-difficult. What made Stropus so special was her ability to track dozens of cars simultaneously. “You had to have a sort of photographic memory,” she explains. “Say five cars go by. You have to know exactly which cars they are. You get the first one and the last one, and then you can estimate the ones in the middle, if necessary.”

Stropus says the Indy 500 was her toughest assignment “because the cars come around so often.” Endurance races were easier even though she was on duty for 24 consecutive hours, with no bathroom breaks. “It’s perfectly fine if you don’t drink. And you’re young,” she says. “You have the motivation because you’re working for the top teams. They’re paying you. They rely on you. You have to do it, and you have to do it right. Because that’s what they expect.”

Worn down by the logistical challenges posed by the arrival of electronic equipment, Stropus pulled the plug on her timing business in 1991. But at 77, she remains as busy as ever. As she puts it: “My life has been and continues to be awesome. I’ve had the best time working for the best people. I had no ambition to be here. I am so lucky to have fallen into this.”