Shifting Tides: How Peugeot's Victory at Le Mans Marked the End of Audi's Era

After more than a quarter of a century as the premier class of Le Mans and endurance racing, LMP1 has taken its final bow. Gary Watkins looks back at the defining moments in the history of the division

Porsche, Toyota and Audi created the finest of the breed with their hybrid LMP1 chargers, all of which triumphed at Le Mans. But now a new era beckons

Getty Images

Taken from Motor Sport March 2021

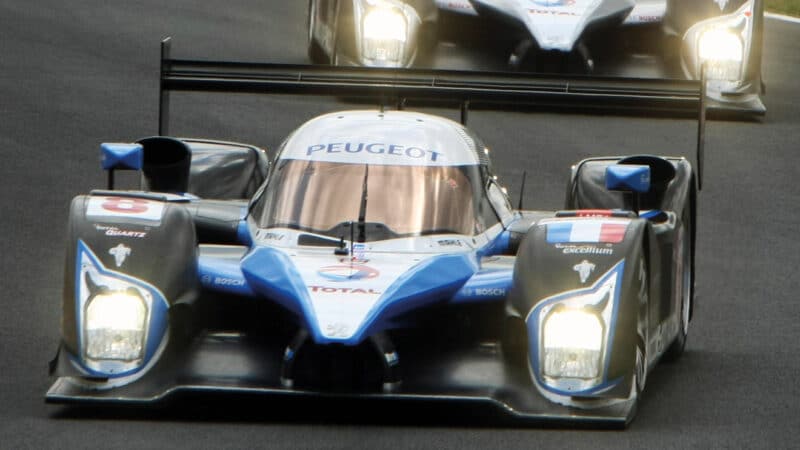

2008: The greatest Le Mans heist

Audi driver Tom Kristensen reckoned Peugeot had “given us a bit of a smacking” at the 2008 Sebring 12 Hours. Another victory a couple of months later at Spa confirmed the French manufacturer as the clear favourite for the Le Mans 24 Hours in the battle of the turbodiesels.

The Peugeot 908 HDi had again proved its supremacy over the ageing Audi R10 TDI at the Le Mans Test Day two weeks ahead of the race. The best of them, with Stéphane Sarrazin at the wheel, was more than four seconds up on the fastest of the German machines over the two sessions held in mixed conditions.

Despite being over five seconds off Peugeot in qualifying, Audi triumphed in 2008

Getty Images

The rain gave Audi hope, however. On a wet track, the R10 was up there with the 908s. For Allan McNish that was the key to the against-the-odds victory that he, Kristensen and Dindo Capello pulled off at Le Mans that year.

“When it rained we were suddenly competitive, a little bit quicker than them,” recalls McNish. “That’s when we knew we had a chance. We saw a chink in their armour and we logged it in the back of our minds.”

That chance, of course, relied on it raining during the race. Audi’s forecast ahead of the start suggested it was going to do just that, but not until the small hours of Sunday morning.

The pace in 2008 was so high that the lead cars had completed 200 laps by the 12-hour mark, and then the rain arrived…

Audi

“We knew with the rain coming we had to be there to be within striking distance to take advantage of a very driveable car in the wet,” explains McNish. “We built everything up to be as perfect as possible so that we could stay in the game: our job was to remain on the lead lap until it rained.

“We drove every lap like a qualifying lap. We were going to a safety car map from the end of the Porsche Curves to try to stretch the fuel and make sure we went a lap longer than we should have done. It was the only way if we were going to hang on in there.”

“We drove every lap like a qualifying lap, but had to go a lap longer”

Hang on in there they did. The only one of the three Audis in contention that weekend was just half a lap back when it started raining shortly after the halfway mark. Ninety minutes later, Kristensen swept past race leader Jacques Villeneuve aboard the 908 he shared with Nicolas Minassian and Marc Gené.

There were a couple of twists and turns to come, but McNish, Kristensen and Capello went on to pull off arguably the greatest heist in Le Mans history.

The battle for diesel supremacy in 2008. Audi lagged behind Peugeot on outright pace, but stole the win via great strategy

Getty Images

1999: Panoz blows the roof off its GT1

“Whoever heard of the horse pushing the cart?” So declared Don Panoz when he took the wraps off the front-engined GT1 racer he was going to take to Le Mans in 1997. The cynicism was muted because he wouldn’t be the first to race a car with the engine ahead of the driver in the class created four years earlier. But when the pharmaceuticals magnate announced a couple of years later that he was going to cut the roof off the car to create an LMP prototype, everyone thought he was joking.

The smirks disappeared when a car initially called the Panoz LMP Spyder notched up a first American Le Mans Series victory at Mosport in June 1999. By the end of the car’s frontline career in 2002 the doubters were laughing on the other side of their faces. What was quickly renamed the LMP Roadster S, and was then updated into the LMP-01 Evo for its final season, ended up with a tally of eight American Le Mans Series wins. Five of those came against the might of Audi.

The preposterous idea to create an open car out of the Panoz Esperante GTS-R, designed and built by British racing car constructor Reynard, originated in the fertile mind of Tony Dowe. One of Tom Walkinshaw’s long-time subalterns, Dowe had been recruited from Arrows to run the Panoz racing operation at the end of ’97, but he quickly got fed up of complaints from the boss that the car wasn’t receiving due recognition for its successes in the GT1 arena in North America.

From left: David Brabham, Jan Magnussen and Don Panoz after Panoz’s DC win, 2002

Getty Images

“Don kept going on about the car not getting the credit it deserved,” recalls Dowe. “I said, ‘Well you’ve got to be winning outright with an LMP1 to get that.’ He told me he wasn’t going to pay for a new car, so I decided to have a look if we could somehow use the existing car. I thought, ‘Why not cut the roof off?’, because I’d done that before.”

That’s a reference to the double Le Mans-winning Porsche WSC-95 that was created out of the Jaguar XJR-14 3.5-litre Group C car in the dying days of TWR’s North American operation. Told he needed to come up with a project to save the company, he persuaded Porsche that he had an IMSA World Sports Car awaiting an engine in what he describes as a “real smoke and mirrors job”.

“It looked like some kind of Mexican lowrider when we had finally finished”

“The problem with the GT1 was that it wasn’t allowed the same width tyres as the LMP1 cars,” says Dowe. “We cut the wheelarches and put the big wheels and tyres on the car. It looked like some kind of Mexican lowrider when we’d finished.”

Jan Magnussen, out of work after being flicked by the Stewart Formula 1 team during 1998, drove the car at its first test at Road Atlanta at the end of that year.

Take a GT1 monster, cut the roof off, fit bigger wheels and voila, you have yourself an LMP1 car. Well, you do if your name is Don Panoz. Yet the crazy plan worked

Getty Images

“Jan had called me because he was looking for a drive, so I suggested he come over for a test,” explains Dowe. “Watching Jan get on the brakes into the chicane at the end of the back straight made the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. He was way quicker than all the prototypes racing in America at that time, so it wasn’t that much of a jump to cut the roof off this thing we’d built.”

Dowe had fallen foul of Panoz’s whims and departed the organisation by the time the LMP1 car made its debut at Road Atlanta in round two of the ALMS in ’99. It was a winner next time out at Mosport with Magnussen and Johnny O’Connell and, more significantly, triumphed at the Petit Le Mans 1000-mile enduro at Road Atlanta in September, David Brabham, Eric Bernard and Andy Wallace doing the driving.

The arrival of the Audi steamroller in 2000 didn’t stop its winning ways. There were some crazy races, most famously the one-off 2002 Washington DC city event on a circuit laid out in a car park. Brabham and Magnussen triumphed over Tom Kristensen and Dindo Capello in a thriller of a dogfight.

Toyota’s late heartbreak at Le Mans in 2016

Toyota was no stranger to heartbreak at Le Mans. The Japanese manufacturer had lost victory in the closing stages in 1994, ’97 and ’98, but it had the win ripped from its grasp with just six minutes left on the clock when Sébastien Buemi, Anthony Davidson and Kazuki Nakajima looked to be home and dry in 2016.

Nakajima was in control even before Neel Jani brought the chasing Porsche into the pits with a slow puncture with just 10 minutes remaining. That gave the leading Toyota TS050 Hybrid an advantage of 80 or so seconds as the cars began their penultimate laps.

Toyota had dominated the 2016 Le Mans over Porsche, but only managed second

DPPI

Less than a third of the way around that lap, a connection on the high-pressure airline between the turbo and the wastegate fractured on one bank of cylinders. Nakajima lost power and crawled around onto the start-finish straight and then stopped right in front of his pit. The Porsche 919 Hybrid Jani shared with Romain Dumas and Marc Lieb sped past the stationary car to take the lead. Toyota’s dreams were over for another year. Nakajima got going after running through a series of resets, but his last lap was too slow for the car to be classified.

It was doubly galling for Toyota. Had the marque been a month or two more advanced with development of its new twin-turbo V6, it might have been able to hang on to win despite the technical glitch.

A distraught Kazuki Nakajima is helped away from his stricken Toyota at the end of the 2016 Le Mans. His final lap was beyond the maximum six minutes, so the car couldn’t be classified

Getty Images

“Our engine worked when all was fine, but there was no back-up mode”

“The development time of the engine had been very short,” says Toyota Gazoo Racing Europe technical director Pascal Vasselon. “We had an engine that worked when everything was fine, but there was no back-up mode. You need software that can handle that kind of situation and at that time we did not have it. A couple of months later we did.”

Davidson perhaps summed it up best. “No one would believe a movie if it ended like this,” he said.

Kristensen’s late arrival at Le Mans in 1997

Le Mans was a race on Tom Kristensen’s target list (see this month’s Motor Sport interview) but a week before the 1997 event he had no plans for it. That changed with a phone call from Joest Racing. Not only would he be making his maiden start, but he’d be doing so aboard the very Porsche WSC-95 that had won the race the previous year.

Joest’s decision to give Kristensen the break that set him on course to become the most successful driver of the LMP1 era followed a protracted period of indecision within the team. It was receiving no support from the factory and wasn’t flush with cash, which resulted in a back-and-forth debate between team owner Reinhold Joest and his technical director, Ralf Jüttner, as they considered who to put in the car alongside ex-Ferrari Formula 1 drivers Michele Alboreto and Stefan Johansson.

“One day, I would say, ‘you know we really must go for someone with some budget’ and Reinhold would reply, ‘but we might be giving up the chance to win’,” recalls Jüttner. “The next day I’d tell him that he was right and he’d go, ‘but you know we really need the money’. We were switching our positions around all the time.”

Kristensen, who was back in Europe after a four-year sojourn in Japan to try and re-establish himself in the motor sport mainstream, was already on the team’s list. But what Jüttner calls “the final kick” to sign him came from former Joest team manager Domingos Piedade, who’d also looked after Emerson Fittipaldi in the 1970s.

A dream debut for Tom Kristsensen alongside Johansson and Alboreto in 1997

DPPI

“Domingos said I should take Tom and that I didn’t need an experienced driver because Le Mans had become a 24-hour sprint,” says Jüttner. “He said the young kids could see like eagles in the night because they were used to be being in the disco…”

The late Piedade’s comments turned out to be spot on. It was during the night that Kristensen offered more than a hint of what was to follow over his illustrious career. He set a succession of lap records over the course of a third stint on a set of tyres. So quick was he, that Jüttner kept him in the car for what at the time was an unprecedented fourth stint.

Jüttner believes that the young gun’s pace motivated Alboreto and Johansson to up their respective games. They were able to match the pace of the leading Porsche 911 GT1 Evo and put it under pressure. The closed-top car failed late on and Kristensen joined the select band of drivers to win Le Mans at the first time of asking. Just eight years later, the Dane had equalled Jacky Ickx’s Le Mans record of six wins and went on to extend that mark to nine before hanging up his helmet.

Birth of the greatest LMP1

Audi might have finished third and fourth on its Le Mans debut in 1999, but the hard truth was it was nowhere. Its first stab at an open-top LMP prototype, the R8R, wasn’t a match for the machinery from BMW and Toyota that slugged it out at the front. A second design, the R8C coupé, was neither fast nor reliable.

A new car was clearly required, and the decision to build one had already been made. It was taken in the weeks after an even more unconvincing race debut from the R8R at the Sebring 12 Hours three months earlier. The result was a machine known simply as the R8, and it would turn out to be one of the greatest sports cars ever, and certainly the most successful of the LMP1 era. Five victories at Le Mans followed, not to mention 50 in the ALMS.

By 2002, Audi’s R8 was already established as the LMP1 benchmark. That year the team locked out the podium, beating the fourth-placed Bentley Speed 8 by 13 laps

DPPI

“It was clear before we even went to Le Mans that we would be doing a new car for the following year,” recalls Wolfgang Ullrich, the long-serving head of Audi Sport and architect of its prototype programmes. “I can’t tell you exactly when it was, but I would say three or four weeks after Sebring.

“We had a programme inked for the following year and we decided that a new open-top car was the right way to go. First we concentrated on Le Mans and then we incorporated everything we had learnt into a new car.”

That gave an incredibly short schedule to get the car up and running in time to be fully tested before the start of the 2000 season the following March. But Audi Sport technical director Wolfgang Appel always joked that he didn’t start work on the new car straight after Le Mans — he waited until the Tuesday…

Dindo smokes ’em – just

Dindo Capello made himself a promise as the clock ticked down on the Mosport round of the ALMS Series in August 2000. He was going to quit smoking if he won the race. It was, however, an empty threat. He might have been leading, but the Joest Audi R8 he shared with Allan McNish was very much the second favourite.

The Audi was still on wet tryes, while Jörg Müller in the chasing BMW V12 LMR was on slicks. The German Schnitzer team had rolled the dice with 20 minutes to go as the track began to dry up after a mid-race shower, bringing in the Bimmer co-driven by JJ Lehto for a change of tyres. The tactic looked like it was going to pay dividends.

Müller inexorably closed down a car that had dominated the race. On the penultimate lap he carved a massive seven seconds out of Capello’s advantage as the Italian struggled with wets on the drying surface. That left the BMW driver four seconds to gain over the final 2.46 miles around the former home of the Canadian Grand Prix.

The wet-shod R8 of Capello just holds off the rival BMW in a red hot, but non-smoking finish

Audi

“I was 80 or 90 per cent sure I was going to lose the race in the final laps”

“I was 80 or 90 percent sure that I was going to lose the race over those final laps,” recalls Capello. “The car was moving around a lot in the fast corners and it was difficult to stop it for the slow corners.

“I think Jörg got a little bit of traffic on that final lap and when I got to the end of the back straight still in front, I said to myself that there was no way I was going to lose the race now. I drove those final three corners as though I was on slicks.”

Capello’s struggling Audi crossed the line a scant 0.148sec ahead of the chasing BMW. The result was generally reckoned to be the closest competitive finish in history for an international sports car race up until that point in time.

The winning driver remained true to a promise he didn’t think he’d have to keep, “little by little” giving up the cigarettes over the course of the following six months. By the beginning of the following season he was most definitely an ex-smoker.

Diesel comes to Le Mans: Three men go into a bar…

Three men sitting in a bar in Ingolstadt in January 2001 shaped the future of the LMP1 division. They didn’t know it at the time, but they set in motion a course of events that once again made the top category of sports car racing a technological proving ground for the automotive industry. Their discussions — drunken, perhaps — centred on the idea of putting turbodiesels on the grid at Le Mans.

The scene of their debate was in the local NH Hotel, the favoured destination of Audi Sport engine boss Dr Ulrich Baretzky when he made the trip from his Neckarsulm facility to visit motor sport headquarters. The other participants late that evening were the two Daniels, Poissenot and Perdrix, respectively the sporting and technical directors at Le Mans 24 Hours organiser the Automobile Club de l’Ouest. Diesel powerplants somehow came up in their postprandial discussions.

“As our wives say, bars are full of drunk men talking cars and football”

“I can’t remember who brought it up, but we ended talking about how 50 per cent of the cars Audi sold around the world were diesels, but there was no motor sport category where you could race one,” recalls Baretzky. “That was the starting point. As our wives always say, bars are full of drunk men talking about cars and football.”

Little more than two years later after “a lot of toing and froing”, according to Baretzky, the ACO duly announced that turbodiesels would be able to race in LMP1 from the following year. It would be wrong to say, however, that Audi’s engine guru was the driving force behind the move. He admits that he was initially against the idea for one simple reason: “I didn’t know anything about diesels.”

By the time the inclusion of diesels in the 2004 LMP1 rulebook was announced the previous March, Baretzky had undergone a change of heart.

A driver change after 21 hours racing, as Emanuel Pirro makes way for Audi team-mate Frank Biela at the 2006 Le Mans 24 Hours

Getty Images

“I realised that I had to do it, because for the rest of my life I’d regret it if I didn’t, if someone else did it first,” he says.

Baretzky’s ideas for a diesel-powered P1 car were met with initial scepticism at Audi, but he found a champion at the very top of parent company, the Volkswagen Group. It was that great innovator with a love of motor sport, Ferdinand Piëch. Baretzky was granted an audience with the architect of the Porsche 917 and the Audi Quattro, then chairman of VW’s supervisory board, in the dead of night at Le Mans 2004.

“My boss at Audi Dr [Martin] Winterkorn said, ‘Come, I want you to explain to someone what you want to do,’” he recalls. “He took me to see Piëch and after five minutes of questions and answers, he told me, ‘You should do it.’ That was enough for me, because Piëch was god.”

Two years later the Audi R10 TDI powered by a bespoke 5.5-litre turbodiesel engine was on the grid at Le Mans. It won the race in 2006 and would remain unbeaten in the 24 Hours over its three-year lifespan with the factory Joest squad.

Shake, rattle and gold

It was meant to be an historic moment. Porsche’s first contender for outright honours at Le Mans this century was about to turn a wheel for the first time. But Alex Hitzinger, the technical director on the 919 Hybrid LMP1 project, knew there was a problem. As good as the new car seemed, the whole thing appeared to be shaking itself to pieces.

A massive vibration from the 919’s twolitre V4 engine could have, he says today, “potentially killed the programme”. What it did do was cause a torrid first six months or so of testing with the car. “Painful” is how he describes the in-house Porsche factory team’s attempts to get on top of the handling and reliability of the rattling machine.

But a fix was already in the works through the second half of 2013 as Porsche geared up for its return to the top flight of sports car racing in the World Endurance Championship the following year. Hitzinger decided that wholesale changes were needed at the rollout on the marque’s Weissach proving ground in June 2013.

“I was standing next to the car and felt the vibration from the engine”

“I remember it as if it was yesterday,” remembers Hitzinger, who now sits on the board of VW. “I was standing next to the car and felt the vibration, so I asked the guys responsible for the engine whether we could cope with it.”

The response was in the affirmative, but Hitzinger begged to differ.

Porsche’s long-awaited return to Le Mans came with its new 919 Hybrid in 2014. While it didn’t win first time out, it laid the foundations for dominance in the years to follow

Getty Images

“I’d inherited the engine concept when I joined the project [in November 2011] and the designers had been very aggressive on the firing order,” Hitzinger explains. “I made the decision right there and then that we had to turn the thing around as quickly as possible. Changing the firing order meant we needed a new crankshaft and camshaft, both of which were going to be long lead time components.”

The revised engine arrived in time for a test at the Algarve circuit in December and the corner was quickly turned. “From that point on we made massive progress in terms of handling, reliability and performance,” says Hitzinger.

He describes the change of direction on the engine as the “golden decision” of what turned out to be a golden programme. By the end of its first season, the 919 was a race winner in the WEC. Over the next three years, the second iteration of the 919 swept to a hat-trick of hat-tricks, Le Mans victory and drivers’ and manufacturers’ WEC titles in 2015, ’16 and ’17.

Scandal drives Audi away

No one knew it at the time, but it was the beginning of the end for LMP1.

Audi dropped the bombshell in October 2016. The German manufacturer announced that it would be walking away from sports car racing altogether at the conclusion of that year’s WEC, taking it away from a category in which it had been an everpresent factor since 1999.

The announcement, described at the time as a realignment of its motor sport future, was tagged with the line ‘Formula E instead of WEC’. But that wasn’t quite true: Audi had already announced that it was stepping up its involvement in the Abt Schaeffler Formula E squad ahead of a fullfactory entry for the 2017/18 season. Formula E was, Audi Sport boss Wolgang Ullrich had explained when that news broke, “an additional programme” alongside racing in the WEC with the brand’s turbodiesel LMP1 machinery.

The architect of all of Audi’s prototype masterpieces, Dr Wolfgang Ullrich

DPPI

But Audi parent company Volkswagen was reeling from the dieselgate scandal that had hit the group just over 12 months previously. The financial liabilities were mounting and money needed to be saved at a time that VW could no longer be seen to be promoting diesel technology.

“It was not an easy period for the group financially or politically,” says Ullrich. “Suddenly, almost from one day to the next, everyone was talking bad about diesel engines. How could we have continued to race a diesel engine? No way.”

It was a swift turnaround for Audi. A new car, building on the all-new 2016-spec R18, was in the final stages of design and some parts had already gone to procurement.

The demise of LMP1 was equally swift. Porsche, also part of the VW Group, announced it would be walking away from P1 at the end of 2017 just eight months later. By September, WEC promoter the Automobile Club de l’Ouest had announced that it was beginning to work on rules for a new breed of car to contest its top division. P1 was in its death throes.

LMP1: The making of the top sports car class

The story of LMP1, from the beginning

1994

Le Mans 24 Hours organiser the Automobile Club de l’Ouest introduces a new class dubbed LM-P1/C90 — note the hyphen — that lumps the new breed of open-top World Sports Cars from IMSA and old-style Group C together. No WSC cars make the trip.

Group C cars are excluded and the class temporarily becomes known as LM-WSC before the LMP1 name makes a return.

1996

First Le Mans win for an LMP1 courtesy of a Joest-run Porsche WSC-95 (left).

2000

Class renamed LMP900 in first year of the Audi R8 to reflect the minimum weight (it had briefly been known as LMP875 in 1997).

2005/06

Staggered introduction of new aerodynamic rules that also allow coupés for the first time.

2011

A rule change mandating only two mechanics can change tyres results in Audi abandoning open-top in favour of a coupé. Dorsal fins mandated in further attempt to stop cars flying.

2014

New energy-based formula introduced which limits the fuel flow to each car’s internal combustion engine.

2016

Audi announces the end of its LMP1 programme.

2017

New rules revealed for 2019 that include hybrids having to run on electric power only after each fuel stop. Porsche cans its programme. The ACO and the FIA begin working on a new top class.

Toyota claims the final overall Le Mans win for an LMP1 car, and commits to new Hypercar category.

LMP1 hits and misses

It wasn’t just the big four brands that proved memorable in the top class

Hits

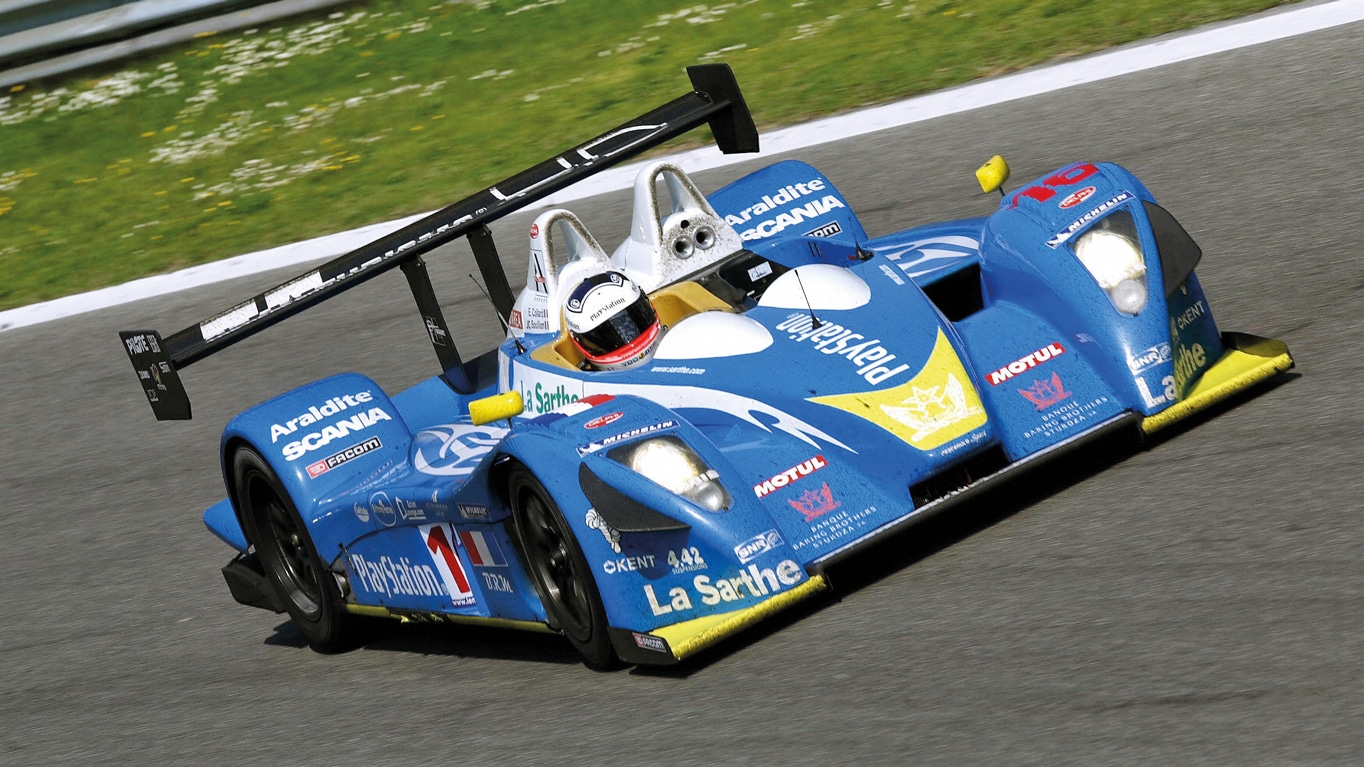

The Pescarolo 01 was arguably the first accessible P1. Henri Pescarolo became a constructor for 2007, creating a design to be sold for either LMP1 or LMP2. It looked great, had great liveries, finished on the podium during its Le Mans debut in 2007, and raced until 2015, by then badged as a Morgan.

A rule tweak to allow the use of production engines in LMP1 led to the marriage of Lola’s B08/60 chassis with Aston’s six-litre V12 from the DBR9. Being petrol-powered it would never realistically challenge the diesels, but the best did finish fourth at Le Mans in 2009. Regardless, name a better looking, or sounding, P1 car. We’ll wait…

Crewe and Norfolk’s answer to Audi’s juggernaut, and it was far more than just a modified R8C. Racing Technology Norfolk may have started out with an Audi platform, but what it rolled out was far more Flying B than four rings. The Speed 8 was unstoppable

at Le Mans in 2003, taking pole and a one-two finish.

Misses

The front-engined GT-R LM Nismo was first shown off in a TV advert during Superbowl XLIX. But, the self-styled ‘LMP1 Bad Boy’ turned out to be just plain bad. Beset by issues, it had no working hybrid, wayward handling and boiled its brakes. Two cars retired and the third wasn’t classified at Le Mans in 2015.

Perhaps the worst manufacturer sports car programme ever? Aston tried an in-house design for 2011. It made three carbon tubs and its own 2-litre turbo straight six. The engine lacked power and rattled itself to bits. They qualified behind the LMP2s in 2011 and did a combined six laps before both were retired and either scrapped or recycled into the Nissan Deltawing.

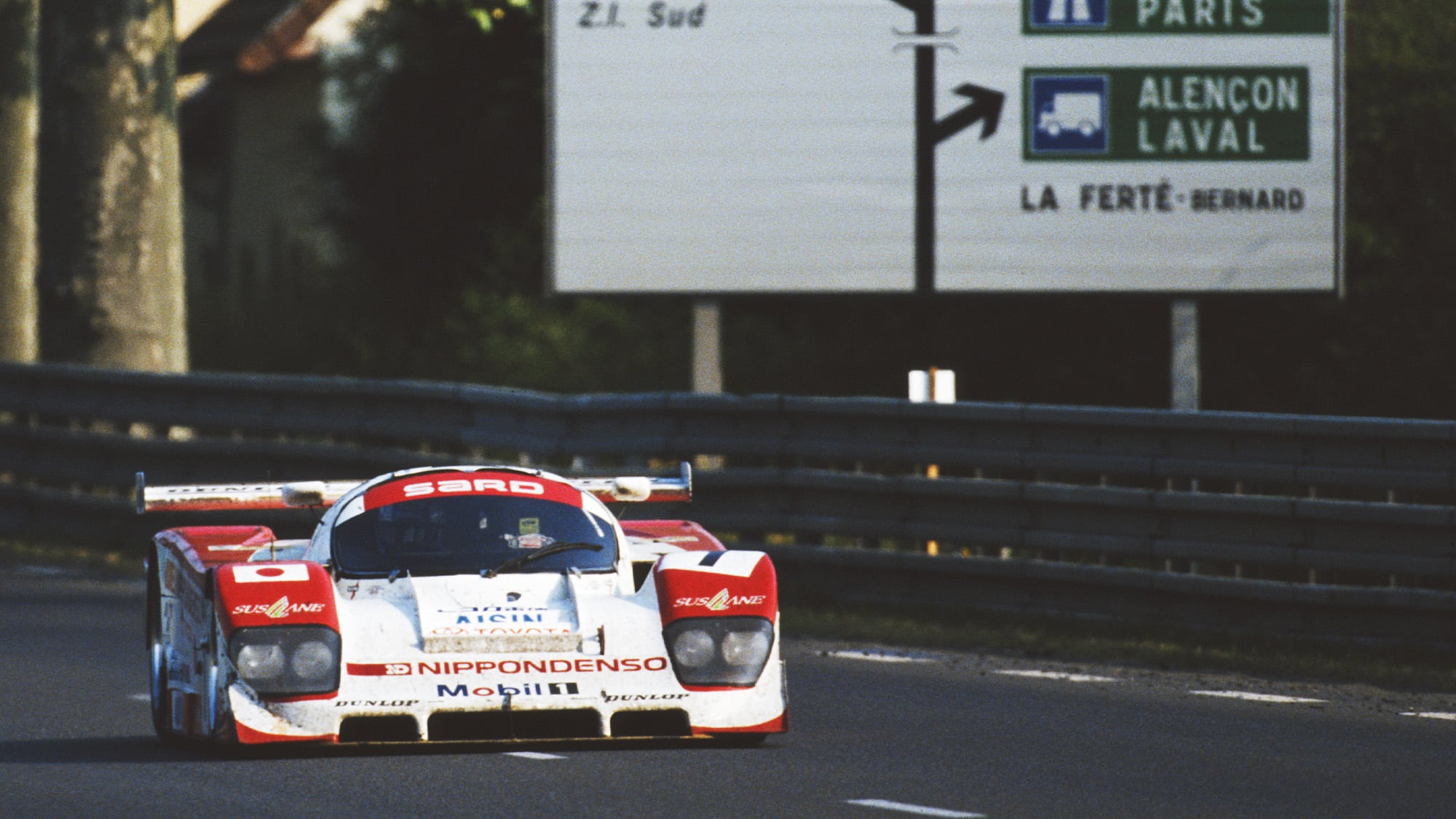

Supposed to be Japan’s glorious return to Le Mans, but turned out to be rather underwhelming. The 2008 S102 had some trick bits and was expected to get among the diesels in qualifying, but was over eight seconds off. During the race it endured multiple accidents and glitches, but still somehow managed to finish.