From Racing Dreams to Grand Designs: The Fearless Spirit of Robin Hamilton

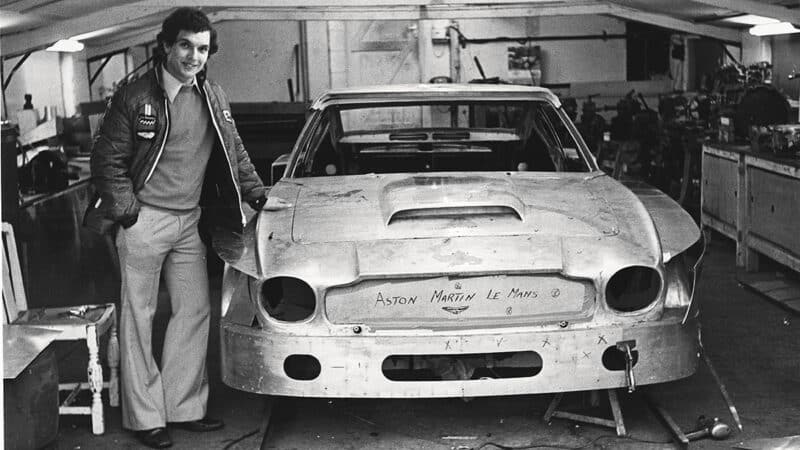

Robin Hamilton took Aston Martin back to La Sarthe in the 1970s and ’80s, but works support ultimately worked against him…

The rolling Derbyshire countryside before us stretches as far as the eye can strain, the murky months of spring doing nothing to dampen our host’s enthusiasm. Robin Hamilton is outlining his most recent endeavour: a house-build on this very plot. Even in its embryonic stages you have to marvel at the sheer bravery of his scheme, much of the thinking behind its construction being highly original. No wonder, then, that it will ultimately be immortalised on the small screen in Grand Designs. It may be a world away from motor sport, yet this project is very much in keeping with his apparent go-it-alone ethos. First and foremost, this former racer knows his own mind.

“You either have the balls to do something or not. But I look back on Le Mans ’77 with mixed feelings, including horror”

“You either have the balls to do something or you don’t,” he quietly intones. “Having said that, I look back on our first attempt at Le Mans in 1977 with a range of emotions, including horror. I don’t know how we did it with what we had; so much could have gone wrong.” That year, Hamilton’s plucky equipe claimed 17th place overall with a car that began life in 1969 as an Aston Martin DBS V8. ‘Le Petit Camion’, as the locals dubbed it, was an unlikely racer, but it made perfect sense to Hamilton: making the improbable probable was a central theme in his competition career. That initial bid followed a raft of equally left-field projects and would also lead to him becoming a constructor in his own right. Hamilton was following a long-term plan and anticipated the road ahead would be cratered with potholes.

“As a child I played with Meccano and blew myself up with chemistry sets,” he smiles. “Then I discovered motorcycles. At 16 I was dealing in them, but what started me off was an Ariel Red Hunter. It was crude but I had this idea to develop and race it. I wanted to take something unsuited for a purpose and make it suitable. By the time I’d finished it could hold off a Manx Norton at Brands Hatch.”

Fast-forward to the dawn of the ’70s when Hamilton was facing an unsure future: “After school I did an engineering apprenticeship with the Rolls-Royce aero division and became a service engineer. Then in 1971 Rolls-Royce went bust. I’d built up a side business dealing in sports cars – many of them Astons – so I began concentrating on them. I became an official service dealer three years later and a distributor in 1977. Our place just outside Burton-on-Trent was a real Aston emporium but there was no swank. We just struck a chord with people who liked what we were about.

Robin Hamilton at his Grand Designs house – another novel, ambitious project

“From the outset I wanted to do more than buy and sell, so I developed my own DB4GT for club racing. It was a great way of promoting the business but it gradually became more serious so we decided to race something else.” Robin Hamilton Motors’ weapon of choice was the DBS. “Even though it was unsuited to being thrown around it had an engine we knew intimately, so we set about developing that and the rest of the car.” Bolstered by decent results in clubbies, Hamilton naturally set his sights on Le Mans. Unfortunately, Aston was undergoing one of its periodical downturns so factory involvement was mostly encouragement-based. “They took a lot of interest in our aerodynamic studies at MIRA. I remember saying they should do a special high-performance ‘Le Mans replica’, but that fell on deaf ears. Then the Vantage appeared, which was the double of our car!

“It went through a number of physical reiterations, too, some of which were ghastly, but we were learning. I remember one phase where it had huge downdraught carbs jutting through the bonnet – spectators loved it.

Ours wasn’t a big company; when you develop a car in public they will see all sorts of things. We knew that in some quarters we’d be slated, but I’d already begun formulating a plan for a purpose-built racing car.”

Hamilton hoped to compete in the 1976 24 Hours, only to be scuppered by a budget shortfall, although he persuaded SAS (a manufacturer of riot gear) to back his bid for ’77. Now bearing the chassis number RHAM1 (Robin Hamilton Aston Martin), ‘The Muncher’ (its internal moniker, coined because of its appetite for brake discs) made its international debut at the Silverstone Six Hours in May 1977. Sharing the car with Hamilton was former autocross star Dave Preece, who spun it into the catch fencing at Becketts during practice. Still, they were running in the top 10 during the first two hours of the race before the diff overheated and flambéed the oil seals. Then came Le Mans.

Hamilton was delighted to finish, even in 17th place overall

“We arrived a few days early and completed building it in the paddock. The French thought we were crazy but they loved the Britishness of it all. The organisers, the ACO, may have turned a blind eye to a few indiscretions as the name Aston Martin still struck a chord with fans. We had all sorts of dramas in qualifying and just squeezed in, although the team was shattered from all the night sessions before the race began. The event itself went well. We ran out of brake discs but Dave, Mike Salmon and I adapted and the old car kept on going. The engine never missed a beat.

“Afterwards there was genuine enthusiasm for what we had done. The press had written us off before we got to France so the sense of achievement was amazing. We were third in the GTP class but had we run in Group 5 we would have been second. We felt a sense of achievement but it didn’t make us complacent – it was just a step forward in our plan. So-called experts said the car was too heavy, which was obvious, but as Aston specialists we couldn’t very well race a Porsche. There were certain features we couldn’t trim down while staying within the rules. The only option was more power, so turbocharging was the way ahead. We set about it ourselves, and at times we were getting 800bhp or more, but the heat build-up was immense. We couldn’t afford a proper intercooler system so I knew we were on thin ice.

“We missed out 1978 and did the ’79 six-hour race at Silverstone as a shakedown for Le Mans. Derek Bell drove the car with Dave Preece and myself. We were thrilled to have him on board and Derek put in some good lap times. He said it was the only car that could reel in the Porsche 935s on the straight. We were getting more experienced and I still think that when we chopped down the roofline we made quite a mean-looking car. It was done for aerodynamic reasons although we found we then had too much downforce at the front. It was hard work to drive and not as fast as it could have been. It overheated and melted a piston early on in the 24 Hours, and that was that. We did one more race [Bell joining Hamilton for the 1980 Silverstone Six Hours] but by then we were concentrating on what became the Nimrod.”

Mention of which is freighted with mixed emotions. “I’d badgered Eric Broadley at Lola about working with us on a new car. He could have taken one look at The Muncher and laughed – it was a tank, but he could see we wanted to do it properly and relented. He agreed to produce the tub and suspension; we’d do the bodywork, ancillaries and so on. The tub was wider than normal as we saw the possibility of a two-seater road-going version at some point. We took delivery of the first one as early as 1979. We didn’t race it sooner because we couldn’t afford to, but we developed a lot of ideas on The Muncher.”

‘Le Petit Camion’ – or Little Lorry – finally made it to Le Mans in 1977

However, the lengthy gestation could have derailed the scheme, as the premier sports car class changed to Group C for 1982. “Actually it didn’t affect us too much,” Hamilton counters. “We had to redo a few things, but not a lot. It wasn’t until early ’81 that the project really got going again. A big catalyst was Victor Gauntlett, a real Bulldog Drummond character who had taken a 50 per cent stake in Aston Martin. I approached Victor within seconds and he was healthily questioning whether we could pull it off. It was agreed that we’d run two cars in the World Endurance Championship, and the US distributor Peter Livanos also wanted in. The biggest problem was coming up with a name for the car. It took days before we arrived at Nimrod, which is a mighty long-distance warrior.

“A condition to the agreement was that we had to use engines from Aston Martin’s Tickford subsidiary, which ultimately became a serious issue for all parties. We had developed our own bulletproof normally-aspirated engine; 500bhp was enough to get started, and we knew how to obtain 600bhp, but understandably Victor wanted some works involvement. We tried to drive the project forwards against real concern over engine reliability – and we were paying for the engines. At every stage, at every event or test, we would encounter problems and it sapped energy from our team.”

“I knew by Autumn ’82 we were in trouble. Livanos had pulled out and poor old victor was suffering financially ”

With Geoff Lees, Tiff Needell and Bob Evans on the driving strength, the factory Nimrod made its debut at the 1982 Silverstone Six Hours. And retired when the camshaft top chain tensioner came loose. At Le Mans Needell was running 10th when he suffered a massive crash following a tyre blowout. Face was saved by a privateer entry. Lord Downe had received the first customer chassis (ultimately, five cars were made), which was entrusted to Ray Mallock to develop with Richard Williams acting as team manager. Having risen as high as fourth by half-distance, it was seventh by the flag despite running on five cylinders. “That was an amazing achievement, although Richard ran his engines at a more conservative level. We as a works team used the performance envelope promised to us.”

The season ended as it began, with the factory squad proving intermittently competitive. The Downe equipe finished third overall in the title chase and would repeat the feat a year on. “I knew by autumn ’82 that we were in trouble. Livanos had pulled out early in the programme and poor old Victor was suffering financially.”

Hamilton’s enthusiasm led on to the Nimrod project, but the Tickford V8 engines proved sadly unreliable

For 1983, Hamilton was forced to go it alone and chose to chase the Yankee dollar. “The European season didn’t start until April so there was no chance of showing what we could do, but the Daytona 24 Hours was in February. IMSA was keen to establish commonality between the US and European sports car regs, so I went over there and was fortunate to meet the right people at the right time: we entered two cars with backing from Pepsi-Cola. If we did well, we were promised backing for the rest of the year. Unfortunately, we were using our last two Tickford engines and both ‘Pepsi Challengers’ failed. In the lead car we had the tremendous pairing of A J Foyt and Darrell Waltrip [the former also driving the winning Porsche 935 K3] alongside Tiff [and Guillermo Maldonado]. We were doing well until the baffle wrapped itself around the crank: the dry sump pan hadn’t been wire-locked and fell out [a similar fate afflicted the sister car]. Pepsi then dropped us, so I did a few more races on a shoestring and we were fifth in that year’s Sebring 12 Hours. Then my bank called in the guarantees, resulting in me liquidating my Aston and Citröen dealerships, both profitable businesses, and Nimrod Racing Automobiles.”

With it died the all-carbon-fibre Nimrod C3. “That was to have been the culmination of all we’d learned since the mid-70s.” Hamilton regrouped and moved away from exotica and racing cars altogether, turning his attention to all manner of environmentally-driven ventures. Nor is he bitter that he didn’t make it further on the race track. “There are two sides to every story, but I wish I’d insisted we used our own engines. A lot of things went on behind the scenes politically, but I’m sure everyone went into it with the best intentions. The circumstances weren’t right and there’s no point dwelling on it. I know the amount of effort that was invested by myself and others, and that’s the important thing. We didn’t just talk about doing Le Mans, about building a car. We actually did it.”