Chapter Five - Jackie The Campaigner

Jackie Stewart’s campaigning spirit will never be beaten, says Damien Smith. And it can be traced back to his experience lying on a canvas stretcher on a filthy floor littered by cigarette butts in the so-called Spa-Francorchamps medical centre in June 1966

Soaked in fuel and only freed from his bent BRM by the efforts of his team-mate Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant, the oft-told story of his narrow escape from that terrible crash at the Belgian Grand Prix, and the dumbfounding sequence of events that followed, has taken on a darkly comedic hue over the years – especially the bit about the nuns… But the trauma of what he went through the day after his 27th birthday triggered something deep within Stewart. It became a totem for his campaigning that demanded a fundamental, awkward and uncomfortable change in attitudes from the cold indifference exhibited by race promoters, circuit owners, the governing body – and even some of his fellow drivers.

The horrors largely went unspoken back then. There was the day in September later that same year when Jackie was racing a Ferrari 250LM at Montlhéry when a driver and two marshals were killed. “As I drove out of the pits, I happened to look to my left and see two dead bodies, shattered beyond recognition, lying just a few metres away from me,” he recalled. It was a sight “more suited to a medieval battlefield” than a sporting venue. The following year at Monaco he stood in the pits having retired his BRM staring at the black plume of smoke rising from the inferno that claimed poor Lorenzo Bandini. And so it went on. Stewart made a point of not being superstitious, but during his racing years he could barely glance at a cemetery. He’d leave for a trip to Spa or the Nürburgring checking the rear-view mirror and wonder whether he’d ever see home again. Then at one circuit, he discovered the chief medical officer was a racing enthusiast, but with minimal experience of neurology, burns or internal medicine. He was a gynaecologist. Enough was enough.

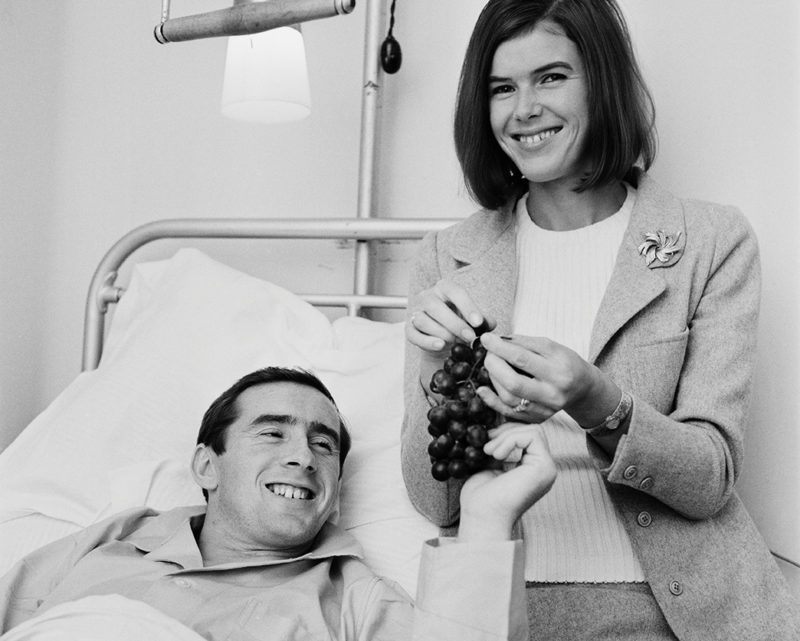

Jackie recuperating at St Thomas’s Hospital, Westminster, in June 1966, after his return to the UK in the wake of his Spa accident. The medical facilities at the circuit had appalled him – another detail that inspired his safety crusade

“Listen, I had a lovely time,” Stewart says of his career. “The only regrets I have are of the people who are sadly no longer with us. My wife Helen counted 57 of our friends who lost their lives driving racing cars. Not all F1, but 57. That doesn’t happen today.”

Stewart’s contribution to the modern racing world today’s drivers take for granted can never be overstated. Especially as he faced ridicule and contempt from so many, including from those whom he held in high esteem. He’d succeeded friends Jo Bonnier and Graham Hill as president of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association in 1968, then worked tirelessly to shake circuits into adopting Armco barriers or lobbying that fireproof overalls become mandatory. “People use to say that if anyone wanted to know where Jackie Stewart lived, they only had to follow the Armco,” he recalled. He started bringing his own doctor to races, an anaesthetist he could trust – and the scoffing grew louder. “In the late 1960s, even some of the drivers reckoned we were pushing too hard,” he said. “At one stage in the pitlane I looked up to see Innes Ireland flapping his elbows and making chicken noises at me.”

Hindsight today makes it easy to scoff at the scoffers. Such attitudes, and the spiteful barbs from our own Denis Jenkinson, haven’t aged well. But even as he was wincing at the hurtful criticism, Stewart understood why he was hated. Danger, bravery, the stiff upper lip… this was motor racing, and Jackie revelled in it as much as anyone. Hell, he’d won by more than four minutes in what today would be considered undrivable conditions at the Nürburgring in 1968. This was a true hero of his age. But still he stuck to his inconvenient truth, earnest in his conviction directly before and after races in which he’d willingly put his life on the line – simply because he was convinced he was right. He was.

Stewart takes to the stage during the 2010 British Racing Drivers’ Club Awards at The Savoy Hotel, London. The Scot had been awarded a BRDC Gold Medal for his “exceptional” contributions to both the BRDC and the sport

The contradiction was there in the campaign’s most profound turning point: the GPDA meeting held at the Dorchester Hotel in London following Bruce McLaren’s memorial service in June 1970. There, Jackie told his fellow drivers it was time to boycott the revered Nürburgring, scene of his greatest triumph. There was shock, disbelief, anger – and then support from battle-hardened Jack Brabham. If he of all people agreed it was time to take a stand… the vote to boycott was seven for, two against, with two abstentions. Meanwhile, Stewart took a call from Jim Hall in America, asking him to race one of his Chaparrals. The pure-blood racer in Jackie couldn’t resist pushing the boundaries, in the very moment he was defiantly arguing the case to step back from them.

The safety baton naturally passed to others once Stewart’s driving career was over, although the GPDA’s power withered without its most vociferous and committed president to drive its demands. Bernie Ecclestone, Professor Sid Watkins and yes, Max Mosley, with whom Stewart always clashed, drove F1 (and with it the rest of motor racing) towards a modern world where the old ways just wouldn’t have been accepted. The change had to come; Stewart just recognised it early.

The trouble was the tub-thumping ‘dog with a bone’ tendency could grate. Again, Stewart was more than aware; again it didn’t dilute his compulsion. But while hindsight shows favourably where motor sport safety is concerned, the picture is chequered when it comes to another of his landmark campaigns: safeguarding Silverstone and the British GP.

It was his old friend and boss, Ken Tyrrell, who asked Jackie to succeed him as president of the British Racing Drivers’ Club. “What have I done to deserve this?” was the immediate response. But of course, Stewart accepted the ‘honour’ and set to work, from 2000, with gusto. This was no figurehead president; it’s just not Sir Jackie’s style.

Stewart tries an experimental fire suit during the 1968 Belgian GP weekend at Spa, scene of his serious accident two years beforehand. Ever since then he had insisted on racing with a spanner taped to his steering wheel, as a safety precaution

His term lasted until 2006, coinciding with a time of turmoil for club and country when it came to matters of F1. Ecclestone and the Mosley-led FIA turned the screw on a scruffy, ageing circuit they rightly judged to be in dire need of investment, while wrongly failing to value or appreciate Silverstone’s long-suffering public. Had they cared, they would never have scheduled the 2000 GP in April, in full knowledge of the mud-bath shambles they were turning the taps to. But the point was taken, because it had to be, and under Stewart’s presidency a multi-million-pound process of rejuvenation began. Today, Silverstone stands tall as a beacon of what’s best about both the business and sport of motor racing. But there remain plenty among the 800-plus BRDC membership who will never give Sir Jackie credit for the part he played. Just as he was in the ‘safety days’, here was a divisive figure who antagonised those who found him overbearing and patronising. He even faced and saw off a vote of no confidence, before stepping down and making way for the balming presence of Damon Hill, who did much to soothe the wounds within the club.

Today, Sir Jackie is deep into what will be his final campaign, one he describes as the greatest race of his life. As his dear Helen slowly succumbs to the cruelty of dementia, Stewart has adopted that familiar ‘enough is enough’ stance one more time. The premise of his Race Against Dementia initiative is that more can be done, right now, to combat the disease. He just won’t accept things as they are, just as he didn’t in the 1960s.

“Sadly Helen can’t walk now,” he told us in January. “She can remember a lot of things from the past, but if you were speaking to her now, four minutes later she would not be able to recall it. It’s a very cruel illness. The statistics are that for everybody born today one in three are going to have dementia, and there is no cure. We have got to do something about it. That’s why I started Race Against Dementia.

Married since 1962, Sir Jackie and Lady Helen Stewart attend the 2015 Autosport Awards in the Grosvenor House Hotel, London. Jackie launched his Race Against Dementia campaign after his wife was diagnosed with the illness in 2014

“When Helen was diagnosed I thought we’ll get to the Mayo Clinic and all the fancy places; money was no object to look after Helen. But zero. I now have seven nurses looking after Helen, two on cycle 24 hours a day. Very few people can afford that. They have to go into a home, and with the pandemic some didn’t see their loved ones for two years.”

Typically, Sir Jackie, at 82, is taking a brazen and unapologetically commercial approach to the cause. The Jackie Stewart Classic, a festival of motoring to be held at Thirlestane Castle in Scotland this June, is geared to raise investment in “young PHDs, choosing the highest-ranking from the most important medical universities in the world” to give them the means to find a cure. “Nobody has ever done it this way before,” he says, and he’s probably right. But then there’s no one else like Sir Jackie Stewart. He’s always chosen his own path, and rarely in his life has he taken the easy one.