Chapter One - Formula 1: If he finished, he won

Reclined in elegant F1 machines Clark exuded graceful serenity. His 25 race wins were characterised by rocket-like starts followed by holding patterns of seemingly effortless control, which had the effect of making racing’s premier category look easy

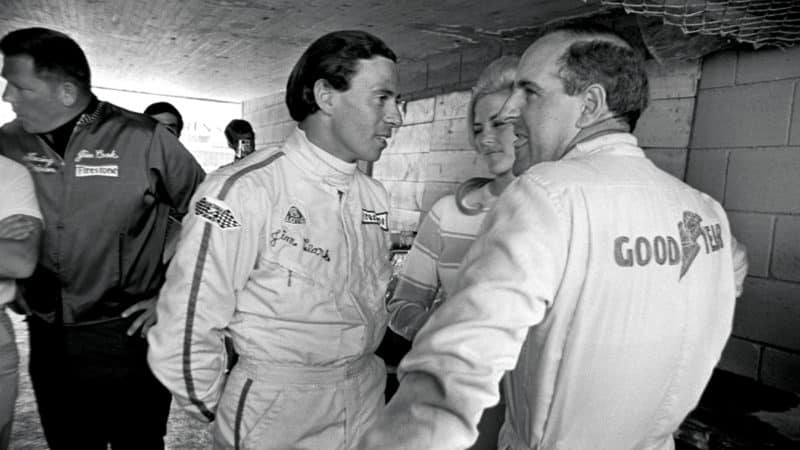

Getty Images

Jim Clark didn’t do second. He finished runner-up once in his 72 world championship grands prix from 1960-68, and 82 per cent of his final tally of 274 points came in victory. In short, if he finished, he won.

And very often he was wondering why his rivals were going so slowly. It came so naturally to this modest man who was never false either in or out of the cockpit.

The bulk of his success was achieved in agile but fragile cars possessed of narrow power bands and perched on narrow tyres the primary trait of which was durability: he won three GPs in succession in 1963 on the same set of Dunlops. Speed had to be harvested and husbanded in a miserly fashion. Stirling Moss had shown the way – shallower entries, trail braking, carrying speed – and Clark took it to the next level. Indeed his was the new model that persuaded the cavalier Moss of the necessity for equal equipment; whether his semi-works deal with Ferrari for 1962 would have provided that is forever theoretical.

Moss’s extended absence and eventual enforced retirement through injury opened the door upon which Clark had been politely knocking for a few months. Whereupon he bolted: regular rocket starts and soaring first laps followed by holding patterns of apparently effortless control and faultless consistency. He could charge when necessary, it’s just that rarely was it so. Tending to lead from gun to tape, usually he had it taped by the first corner.

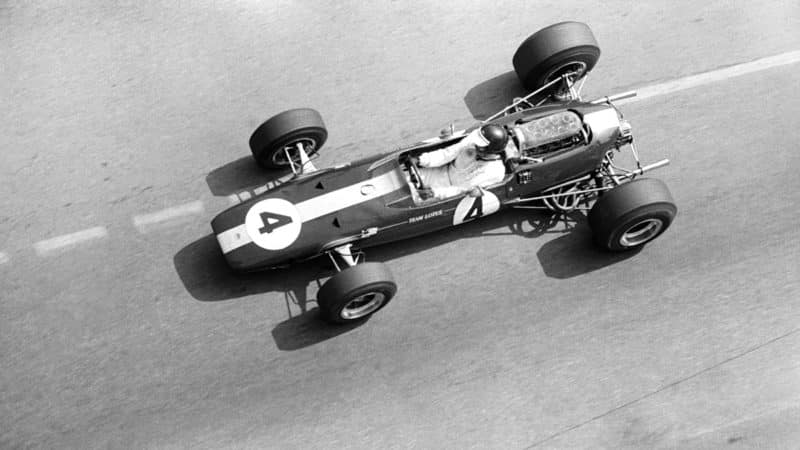

Clark aboard the recently launched Lotus-Cosworth 49 at Silverstone in 1967. He had won on the car’s debut at Zandvoort in June – and six weeks later he would record its second GP success, at Silverstone, in what turned out to be his final race in front of a home crowd

Getty Images

No other racing driver has made domination appear so easy. It might have been mundane but for the beauty contained within. Reclined in elegant machines wrapped tightly around him, Clark exuded graceful serenity. Engines were cosseted. Gearboxes cajoled. Pads caressed. Brakes were released early rather than buried too late in seeking the final tenth. Man, not machine, was its source in this instance.

That’s not to say that he did not benefit from superior equipment. Colin Chapman’s Lotus mined a rich seam of mechanical grip beyond the reach of others. Nor can it be denied that Clark received preferential treatment over bamboozled team-mates. But if opposites attract – and country boy Clark and the urbane Chapman were poles apart in myriad ways – then for sure the best simply seek out the best.

In an era bejewelled by Jack Brabham, Dan Gurney, Graham Hill, Jochen Rindt, Jackie Stewart and John Surtees, Clark shone the brightest. But for oil leaks in the deciders of 1962 and 1964 he would have been F1 champion four times consecutively. His titles of 1963 and 1965 were signed and sealed early. At a time when reliability could not be relied upon, he routinely strung together victories. Notoriously indecisive in life and in the habit of chewing his nails, he had no such worries when at work – except that he was operating in the sport’s most dangerous era.

Clark detested high-speed Spa-Francorchamps, with its capricious microclimate and innumerable unprotected traps for the injudicious. Yet he won four straight GPs there. The faces he pulled as he passed the pits in the thunderstorm of 1963 spoke volumes – as did his lapping of the entire sodden field. And Stewart – the Robin to his Batman – is adamant that Clark would occasionally speed up while leading in 1965 in order to dissuade a relatively inexperienced rival, cherished friend and compatriot from giving more earnest chase. Spa could bite, as Stewart would discover in 1966.

Clark, Lotus 25 and Chapman blend with parked traffic and cyclists ahead of the 1962 Belgian GP, where the Scot came through from 10th on the grid to beat Graham Hill by more than 40sec. Hill took that season’s title after an oil leak sidelined Clark in the South African finale

Getty Images

Clark celebrates his third victory of the 1962 World Championship season, at Watkins Glen. He beat title rival Graham Hill (BRM) by 9sec as the pair of them lapped the rest of the field – and victory kept alive the Scot’s hopes of taking the crown for the first time. There was just one race remaining… 83 days later in South Africa! Clark was on course to win there, too, until his engine broke

Grand Prix Photo

Clark in celebratory mood at Silverstone after the corresponding race one year beforehand

Ronald Dumont/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Feeling the strain: Clark at Monaco in 1964. Having taken pole, he looked a good bet for victory… until his Climax engine began to misfire in the closing stages, due to fading fuel pressure. He was classified fourth after it seized completely on the final lap

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark in full flight at Monaco in ’64, at the wheel of the interim Lotus 25B – he had crashed the team’s new Type 33 at Aintree, so raced an older chassis with updated rear suspension. Despite his aptitude for the track, victory in Monte Carlo remained ever elusive

Lichfield Archive via Getty Images

A relaxed Clark at Monza in 1964. Team Lotus had two of its latest 33 chassis on hand, for Clark and Mike Spence, but the Scot chose to race an older 25. Although Ferrari had a power advantage – and John Surtees eventually won for the home team – Clark was in the lead battle until engine problems struck

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clutch failure caused Clark’s eventual retirement, while McLaren won after Hill suffered a late engine breakage

Philippe Bataillon / INA via Getty Images

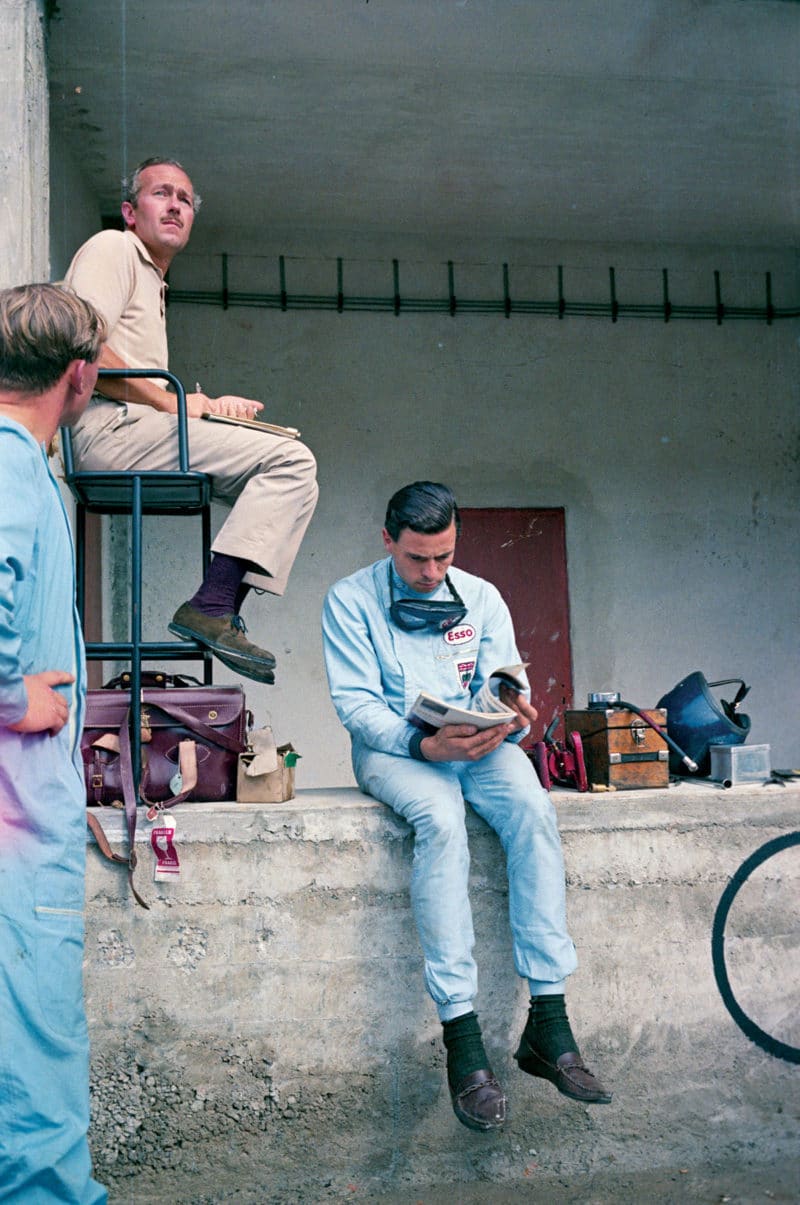

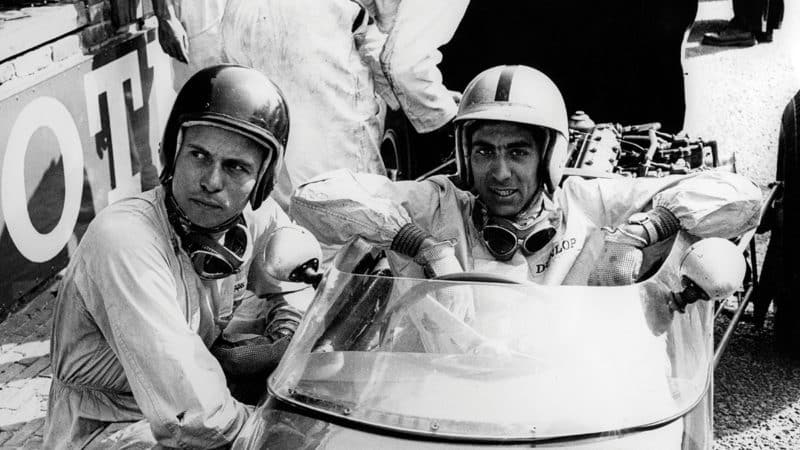

Monza 1963: Colin Chapman looks anxious about something during practice for the Italian GP, while his talisman nonchalantly flicks through a magazine. In the race, round seven of 10, Clark scored a fifth World Championship victory of the season to secure his first title

Gerard Gery/Paris Match via Getty Images

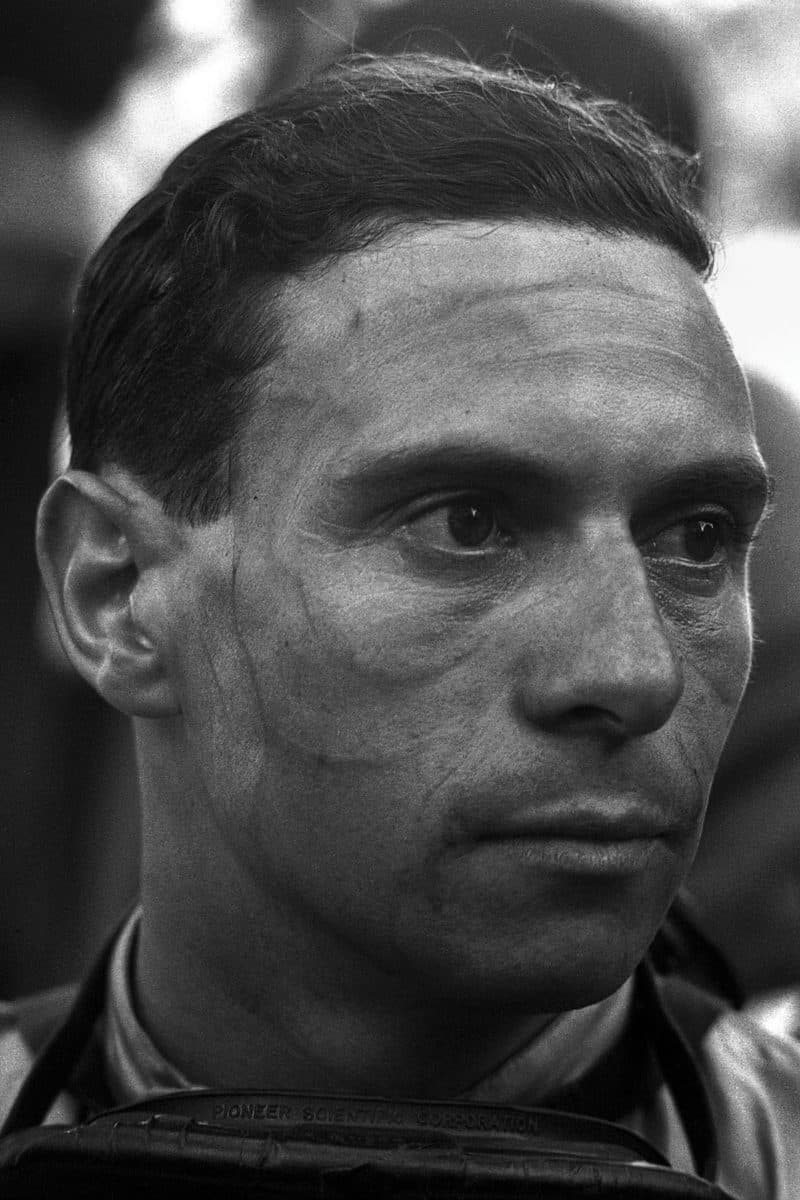

Clark gives photographer Bernard Cahier a quizzical look ahead of the 1965 British GP at Silverstone, scene of one of his most memorable victories. With his car misfiring in the race’s closing stages, he adapted his driving and coaxed it to victory ahead of the charging Graham Hill

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Writing in Motor Sport’s July 1965 edition, Denis Jenkinson described Jim Clark’s Belgian GP victory as “a remarkable demonstration of prowess”. Clark nursed his Lotus 33 for a couple of laps when its clutch began to slip, but the problem cleared and he finished well ahead of Jackie Stewart, the only driver not to be lapped

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark was wary, too, of the almost doubling of power wrought by the introduction of the 3-litres. Yet he won first time out in the groundbreaking Lotus 49/Cosworth DFV package. A changing tax status had prevented his sampling the car beforehand and he qualified only eighth for that 1967 Dutch GP at Zandvoort. He took the lead on lap 15.

Tellingly, he had during practice refused to drive it until the problem – a broken ball-race in the right-rear hub – that he had sensed the previous day, but which had eluded his mechanics overnight, was traced and fixed. He was not the most technical, and an ability to drive around problems could queer testing sessions, but his sixth sense was strong.

The courage of his convictions and self-worth were strengthening, too. His relationship with Chapman on a more equal footing, he seemed increasingly comfortable in his own skin and more worldly – Tasman tan, Colgate smile – and ready, in a way different from the more businesslike Stewart’s, for F1’s impending shifts of slicks and wings, improving safety and sponsor’s stickers…

Like Moss, Clark was 32 when his career was cut short. Sadly there the comparison ends.

Poignant shot of Clark and Lotus team-mate Alan Stacey at Spa in 1960. Stacey was one of two drivers killed during the race, along with compatriot Chris Bristow. Two other British drivers – Stirling Moss and Mike Taylor – had been seriously injured in practice accidents

Getty Images

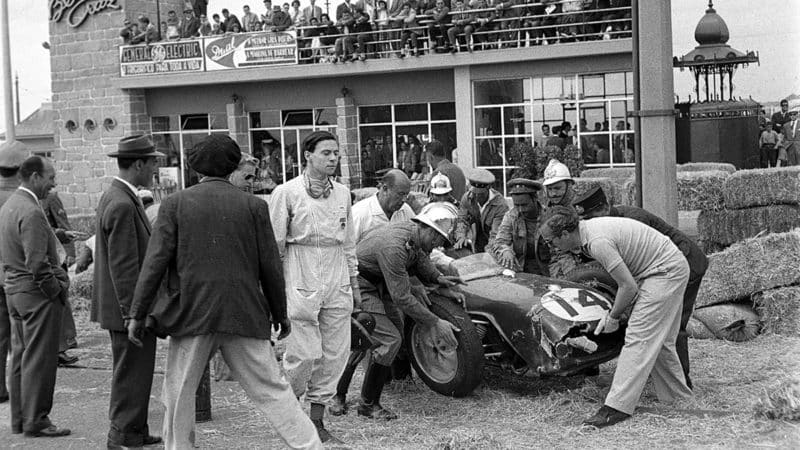

rookie Clark winces as his damaged Lotus 18 is recovered, following a rare mishap during practice for the 1960 Portuguese GP on the streets of Porto. He bounced back to take third place, his first podium finish in a World Championship Formula 1 race

Getty Images

Clark and Lotus team-mate Innes Ireland at Monaco in 1961

Getty Images

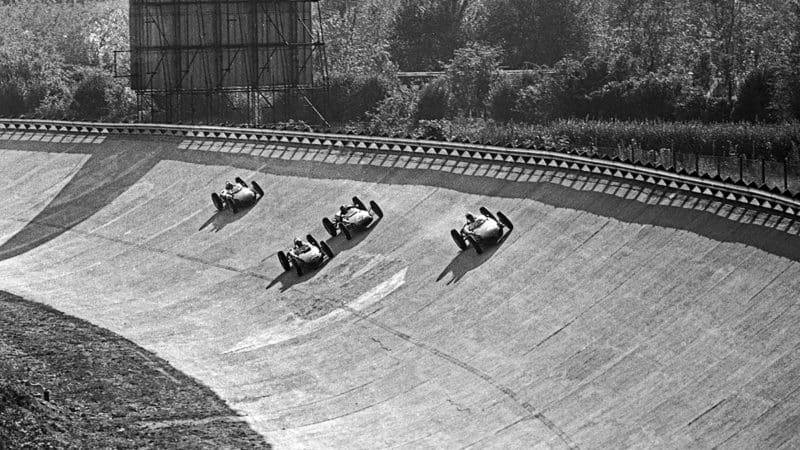

Clark’s Lotus sandwiched by the Ferraris of Richie Ginther, Phil Hill and Ricardo Rodríguez during the opening lap of the 1961 Italian GP at Monza. On the second, the Scot would be involved in a terrible accident that claimed the lives of Ferrari driver Wolfgang von Trips and 14 spectators

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Mersey beaucoup: Clark dominated the 1962 British Grand Prix, leading away from pole position and going on to finish almost 50sec clear of John Surtees to record his first of five such successes. It was the last British GP to take place at Aintree, on a circuit that ran partially parallel to the celebrated Grand National steeplechase course

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

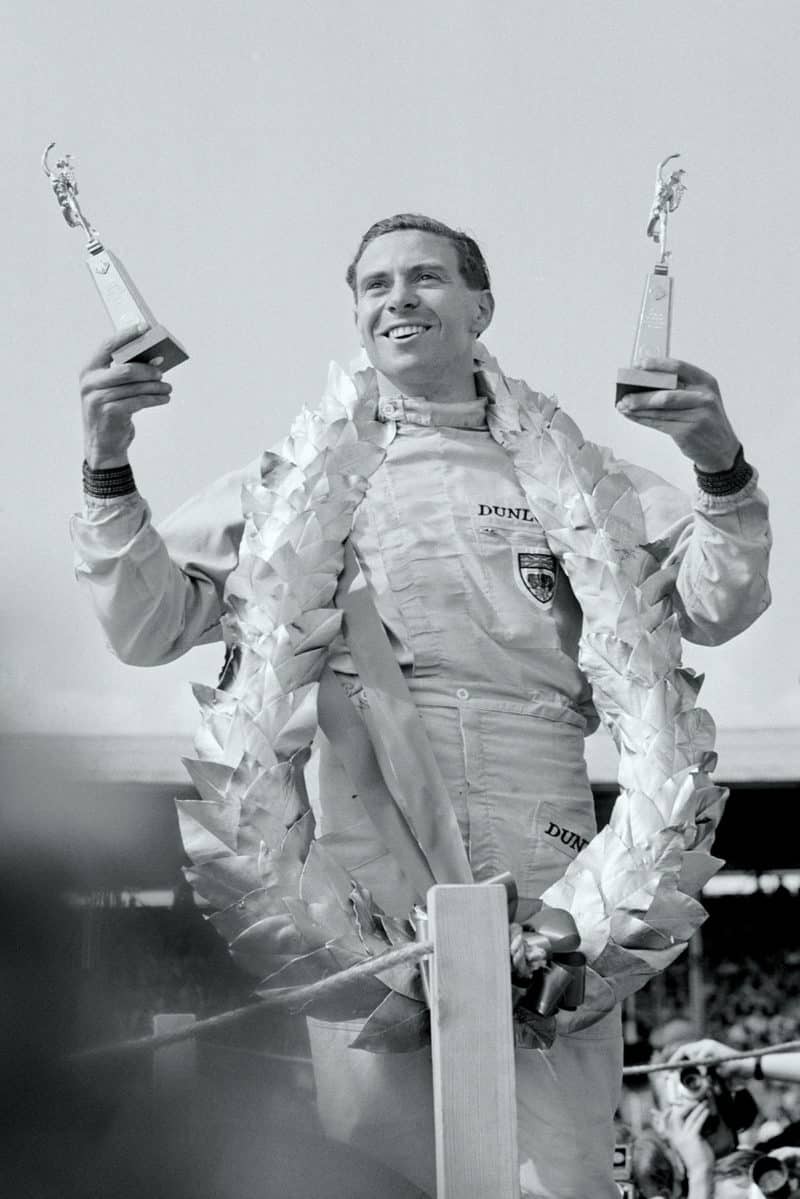

Clark receives the laurels after his runaway success. The GP track closed after the 1964 season, though a shorter version remained in use for club events until 1982 – and continued to host motorcycle racing until 2018. Such activities were suspended the following season, pending essential update work, but there were subsequent moves to reopen the venue… for the two-wheeled community, at least

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark and Dan Gurney (Brabham) lead the field away at Brands Hatch in 1964, as the Kent track hosts the British Grand Prix for the first time

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Where is everybody? Clark was in a class of his own in the 1963 British GP. He beat Dan Gurney to pole by a couple of tenths, but pulled away in the race and won easily – despite staying in top gear towards the end to save fuel, as he was worried the car had not fully been filled prior to the start

Victor Blackman/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

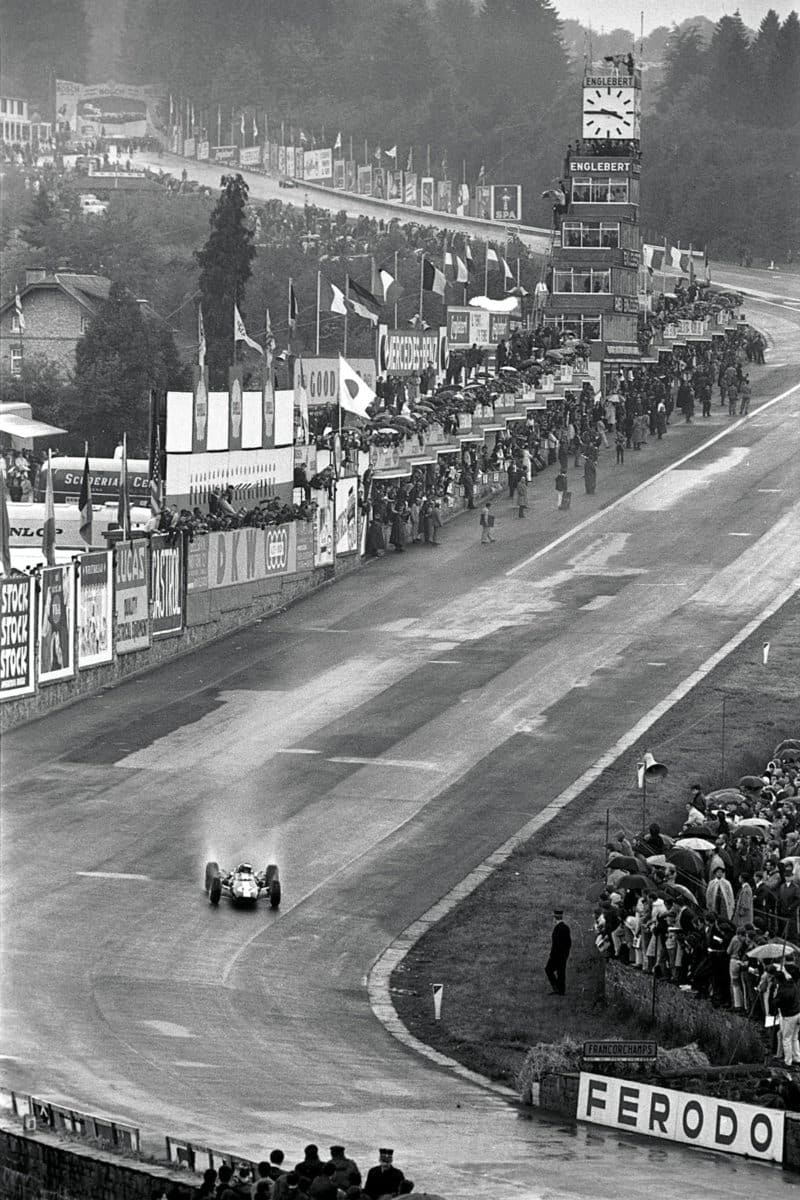

The first World Championship victory of Clark’s successful 1963 campaign came at Spa. Gearbox trouble restricted him to eighth on the grid, but he made a scorching start to lead from the early stages of the opening lap and was never seriously troubled during a race notable for increasingly heavy rain

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Mexico, 1964. Clark was poised to take his second straight world title until an oil line came adrift from his Lotus 33 in the closing stages. The engine seized as he started his final lap, denying him the chance to become the only driver to win the F1 and British Saloon Car Championship titles in the same season

Robert Riger/Getty Images

At the Nürburgring in 1962, Clark was so busy trying to defog his goggles – after a downpour delayed the start – that he forgot to switch on his fuel pump and was left well behind at the start. He eventually worked his way up to fourth place, some way behind a close lead battle between winner Graham Hill (BRM), John Surtees (Lola) and Dan Gurney (Porsche)

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

The Nürburgring, 1967, and the far-off days of a 4-3-4 grid. Clark sits on pole for the German Grand Prix, ahead of Denny Hulme (Brabham), Jackie Stewart (BRM), the Eagles of Dan Gurney and Bruce McLaren, John Surtees (Honda) and Jack Brabham (Brabham). Hulme won; Clark retired with suspension trouble

Grand Prix Photo

Clark and Colin Chapman engage in a quick post-race chat after the 1963 German GP, while winner John Surtees focuses on his bottle of water. Clark had led initially, but his Lotus’s Climax engine lapsed onto seven cylinders and left him powerless to resist the Englishman’s challenge. In 72 World Championship GP starts, this would be the only time he finished second

KEYSTONE-FRANCE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Front row of the grid at Monaco in 1962, with Clark on pole – for the first time in his F1 World Championship career – from Hill (BRM) and McLaren (Cooper)

Grand Prix Photo

Clark gives chase to Jack Brabham’s Lotus 24 at Monaco in ’62. The Scot had been forced to recover after more or less coming to a halt at the first corner, where the fast-starting Willy Mairesse triggered a chain-reaction accident. Only five cars were running at the finishClark gives chase to Jack Brabham’s Lotus 24 at Monaco in ’62. The Scot had been forced to recover after more or less coming to a halt at the first corner, where the fast-starting Willy Mairesse triggered a chain-reaction accident. Only five cars were running at the finish

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Flamboyant Watkins Glen starter Tex Hopkins prepares to send the field away ahead of the 1965 United States GP, with Mike Spence closest to the camera and team-mate Clark just ahead.

Grand Prix Photo

Clark concentrating at Zandvoort earlier that season

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Although Lotus was one of several teams not yet fully prepared for the newly implemented 3-litre Formula 1 regulations, Clark still managed to qualify on pole for the World Championship season-opener in Monaco. Suspension failure put him out of a race won by compatriot Jackie Stewart, whose BRM was one of only two cars to run the full distance. Final finisher Bob Bondurant was classified fourth, five laps in arrears

Grand Prix Photo

The Nürburgring, 1967, and the far-off days of a 4-3-4 grid. Clark sits on pole for the German Grand Prix, ahead of Denny Hulme (Brabham), Jackie Stewart (BRM), the Eagles of Dan Gurney and Bruce McLaren, John Surtees (Honda) and Jack Brabham (Brabham). Hulme won; Clark retired with suspension trouble

Grand Prix Photo

Clark heads for victory in Germany on August 1, 1965 – his sixth win in that season’s seven races to date (and he’d missed the other one, in Monaco, because he was busy winning the Indy 500). That was enough to put him beyond rivals’ reach; he was world champion for a second time

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark in his Lotus 43 at Watkins Glen in 1966, when he notched up the only F1 World Championship victory for BRM’s complex H16 engine. It would be his sole grand prix success during a campaign in which the Repco-engined Brabhams proved to be the cars to beat

Alvis Upitis/Getty Images

Clark celebrates a winning start for the new Lotus-Cosworth 49, after guiding it to victory in the 1967 Dutch GP at Zandvoort

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

the 1967 Monaco GP would be Clark’s final World Championship start with a Climax engine – and also his last race in the principality. He qualified fifth, but retired from the race with suspension failure. The new Lotus 49 was just around the corner

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark at Spa in 1967, where he qualified on pole and led until being obliged to pit for a fresh set of spark plugs. Jackie Stewart took control thereafter until gear selection problems intervened. Dan Gurney pounced to score Eagle’s only F1 World Championship success, just seven days after his victory at Le Mans. Quite a week, that…

GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Clark in the pits during the 1967 Mexican Grand Prix, in the company of Brabham rival Denny Hulme. Despite having to cope with a clutch that malfunctioned for pretty much the whole race, Clark won quite easily. Third place was enough to make Hulme New Zealand’s first – and, so far, only – motor racing world champion

Grand Prix Photo

lark and Graham Hill celebrate a 1-2 for Lotus in the 1967 United States GP.

Bettmann Archive, Getty Images

More entertaining than a set of lights, Watkins Glen stalwart Tex Hopkins gives the starting order. Hill led until clutch trouble allowed Clark to steal ahead. Suspension damage obliged the Scot to nurse his car for the final two laps but he would win anyway

Bettmann Archive – Getty Images