Chapter Four: Sports cars & saloons - Just show him a steering wheel...

Such was Jim Clark’s uncanny natural ability, he could take the wheel of any type of vehicle and immediately demonstrate his mastery. Onlookers watched and wondered, awed by this quiet competence

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

lark could drive anything, anywhere – often winning in a wide variety of cars on the same day. And his experiences ranged from mud-plugging Mini Moke to wallowing ‘Yank Tank’, from 200mph Indycar on a twisting Swiss mountain road to two-stroke and three-wheeling saloons, and from the Lister-Jaguar ‘Flat Iron’ to a flat-over-crest rally car.

His performance on the 1966 RAC Rally was astounding, matching the Scandinavians in the forests after a single day’s testing in Kent woodland. Experienced Brian Melia’s disappointment at losing his Lotus Cortina drive to Clark was quickly subsumed by admiration as he viewed from the co-driver’s seat the Scot’s rapid adaptation and rare speed: here was a potential champion.

Even the eventual accident was a “proper job”, leaping a Scottish ditch, digging in and rolling: “We tripped over the Border!” joked Clark, clearly happy to be home for a time and having fun. Not wanting it to end, he insisted that they stay on to spectate. The team, wary to begin with, loved him.

Rallying had also provided him with his first 100mph experience when he took the wheel of a ‘Big Healey’ on the 1955 Scottish Rally. Car owner, co-driver and cousin Bill Potts’ urgings of caution also quickly gave way to admiration: this 19-year-old had the situation entirely under control.

Not that Clark always felt so. Having recorded the first 100mph sports car lap of a British circuit – at Yorkshire’s Full Sutton in Border Reivers’ Jaguar D-type in April 1958 – he had his parameters reset a few months later when the Lister-Jags of Masten Gregory and Archie Scott Brown, dicing for the lead of the Spa GP, scratched past when lapping him. Clark, whose first experience of a Continental road circuit this was, considered stopping racing there and then – even before a pall of smoke signalled compatriot Scott Brown’s last moments.

Just over a year later Clark would be faster than Gregory as they shared Ecurie Ecosse’s Tojeiro-Jaguar in the RAC Tourist Trophy at Goodwood. Hey, he could do this.

Clark looking casual in Pierre Bardinon’s Ferrari P3/4, about to tackle the latter’s private Mas du Clos circuit in France – though reportedly the Scot wasn’t impressed by the car. In 412P spec, chassis 0848 had raced at Le Mans in 1967 for Scuderia Filipinetti, although Jean Guichet and Herbie Müller failed to finish

GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

But he would still have considered himself an amateur when in June 1960 he was third at Le Mans, aboard an Aston Martin in which he more than matched co-driver Roy Salvadori, winner the previous year in a sister car. (Clark had also beaten power-packed Moss in the public display of anticipation, agility and co-ordination that was the run-and-jump start. Here was a rival to be reckoned with on every level.)

Clark’s sports car opportunities as a professional would, however, be limited not only by Chapman’s continued refusal to attend Le Mans, which he considered a race between the French and a bunch of other mugs, but also his inability to provide a competitive ‘big banger’ with which to contest the lucrative Can-Am series: Chapman had a blind spot over the Lotus 30, which looked unmanageable even in Clark’s hands.

But there was that time his 95bhp Lotus 23 whistled into view with a 28sec lead after the greasy opening lap of the 1962 Nürburgring 1000km. Clark would still be leading 12 laps later when he slid into a ditch, overcome by exhaust fumes. The extraordinary could be expected whenever he took a start.

Chapman had spotted that special something from the moment of their hectic dice in, ahem, matching Elites – it’s likely that the Guv’nor’s factory car was superior to any production/privateer version – at Boxing Day Brands Hatch in 1958. Chapman, a fast and experienced driver, and hardly lacking self-confidence, got the better of it when a backmarker got in the way – but his ‘discovery’ of Clark was the more important result that day. His combining of this Next Big Thing with his Next Giant Leap would regularly reshape the sport.

They would become its dominant force, in fact, global names and faces; front men to a brand of burgeoning worth in need of protection. The mercurial Chapman, though he would eventually overstretch himself on several fronts, was (mainly) in his element; Clark was (decreasingly) less so.

But whenever those demands beyond his control became too irksome verging on stressful, he could shrink himself into a cockpit, be swallowed by a cabin, and thrill to his skill – just as he had when flinging the familial Sunbeam saloon around an autotest’s cones, or when good friend Iain Scott Watson secretly entered him and loaned him a car for his first race, in June 1956.

The windswept Crimond airfield in north Aberdeenshire was most definitively an outpost of motor racing. And Clark would finish last in that smoking, ring-a-ding-ding DKW; the only car he had passed was coasting into retirement. But he had been considerably quicker than the car’s owner. Thus Scott Watson was the first but far from the last to wonder exactly how Clark was going so quickly.

A world away from Monte Carlo, young Borders farmer Clark puts his Sunbeam Talbot Mk III through its paces in 1956, during an MG Car Club driving test in Edinburgh. The event took place at Leith Fort, built in the late 18th century to defend the local harbour

A decade beyond those driving test exploits, the now double world champion assists with maintenance on his Lotus Cortina during the 1966 RAC Rally. The battle scars reveal how hard he’d been trying – and he underlined his versatility by matching the stars of the day

Mcklein/Reinhard Klein/Colin McMaster/LAT

Clark in action during the 1961 Nürburgring 1000Kms, when he shared Essex Racing’s Aston Martin DBR1 with Bruce McLaren. They qualified the car eighth, but a broken oil pipe put them out of the running after 23 of the 44 scheduled laps

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Larking around with Rosemary Smith in the Oulton Park cafeteria, during a break in the 1966 RAC Rally. Outright winner of the 1965 Tulip Rally, Smith finished a class-winning 14th overall in her Hillman Imp; Clark produced a dazzling performance, but eventually rolled his Cortina on the Glengap stage

Markey/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Clark and F1 team-mate Trevor Taylor shared this Lotus 23 in the 1962 Nürburgring 1000Kms – and the Scot tore into the lead at the start, pulling away from more powerful cars by up to 16sec per lap in damp conditions. Suffering the effect of fumes from a leaking exhaust, however, he later crashed

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark teamed up with respected co-driver Brian Melia for the 1966 RAC – and also tested extensively beforehand, in the company of rally star namesake Roger, a sign of how seriously the Scot took the event. The result? He set three fastest stage times and ran mostly in the top six before retiring

Mcklein/Reinhard Klein/Colin McMaster/LAT

After a troubled practice, which restricted him to only a few laps in the Essex Racing Lotus 23, Clark ran a comfortable third in the early stages of the 1962 Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch. His race didn’t last long, however, because his clutch disintegrated

Copyright McKlein / Reinhard Klein / Colin McMaster 2021

Clark tweaks his Lotus 23’s mirror before the start of the 1962 Autosport Three Hours, at Snetterton. He finished seventh overall and second in the 1.6-litres class, which was won by the Elva Mk6 of Desmond ‘Dizzy’ Addicott. Mike Parkes (Ferrari 250 GTO) took outright victory

Photo by Staff/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Clark heads for another British Saloon Car Championship win at Brands Hatch in August 1966, when he finished almost 5sec clear of Jackie Oliver’s Ford Mustang. The race supported the Guards Trophy, from which the Scot was black-flagged when his Felday-BRM leaked oil

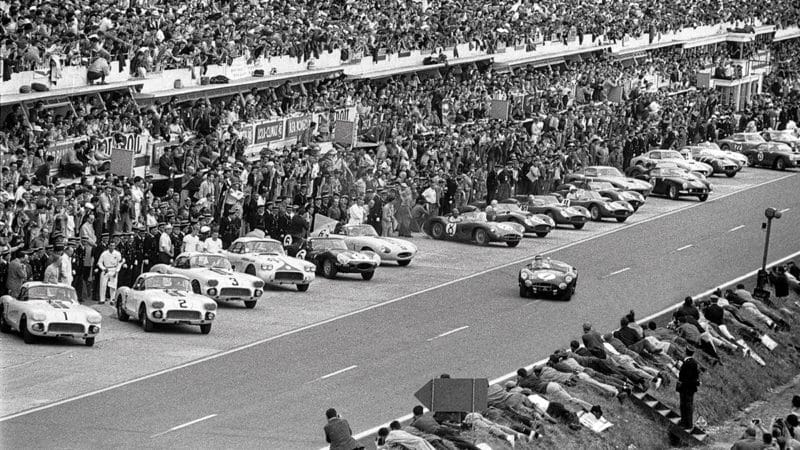

A flying start for Clark at Le Mans in 1960. Partnering Roy Salvadori in the Aston DBR1/300, the Scot finished third – his best result in the event

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark chases the Stirling Moss/Graham Hill Ferrari 250 SWB at Le Mans in 1961. He shared the Border Reivers Aston Martin DBR1/300 with Ron Flockhart, but the car retired before half-distance with clutch failure. A broken water hose accounted for Moss and Hill

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark steers Ecurie Chiltern’s Austin Healey 3000 through Bottom Bend (now Graham Hill Bend) at Brands Hatch in October 1960, on his way to third in a 10-lap GT race. He was beaten by Graham Warner (Lotus Elite) and Chris Lawrence (Morgan +4), but won the over 2.0-litre class

GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Clark, co-driver Brian Melia and crew before the 1966 RAC Rally – the modern equivalent would be Lewis Hamilton taking part in Wales Rally GB

Mcklein/Reinhard Klein/Colin McMaster/LAT

ack Sears (Shelby Daytona Cobra), Clark (Lotus 30) and John Surtees (Lola T70) pose for Bernard Cahier ahead of the 1965 Tourist Trophy at Oulton Park. Denny Hulme (T70) took aggregate victory after a brace of two-hour heats; Clark suffered transmission failure

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Clark with Border Reivers’ Lotus Elite in the Le Mans pits, 1959, when he and John Whitmore finished 10th overall, second in class. It was the Scot’s first of only three starts in the race, a statistic not helped by Lotus boss Colin Chapman’s refusal to go back after an eligibility row in 1962

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Clark in his Triumph TR3 on the Rest-and-be-Thankful hillclimb, Glen Croe, in 1958. The venue was in use from 1906-1970. Assessing the course in Motor Sport, Denis Jenkinson wrote that it was “first-class, but needs to be 10 times as long by European standards”

William Henderson , The Bill Henderson Collection. All Rights reserved.