Unforgettable and Inspiring: Uppity Chronicles Willy T Ribbs' Triumph Over Adversity

Controversial, talented, hindered and shunned – the story of Willy T Ribbs is a hard-hitting one

Willy T Ribbs fought a constant battle against racism in American motor racing, and his career has now been immortalised by Netflix

Uppity, the story of Willy T Ribbs’ incredible journey through racing, stands alone in the cannon of motor sport films, and is something of a rarity when compared to sport biopics across all disciplines. With big names such as Bernie Ecclestone, Bobby Unser and Rick Mears lending their views, the stature of those involved in the film shows the respect Ribbs garnered in a career laden with immense challenges and controversy.

Unlike the on-road artistry of the Fangio documentary A Life of Speed, the motorised machismo of TT picture TT3D: Closer to the Edge or the stock-block brawn of Le Mans film The 24 Hour War, Uppity reveals Ribbs’ struggle against prejudice and discrimination in the 1980s and ’90s – mostly due to his skin colour.

Ribbs was the first black person ever to drive a Formula 1 car, breaking through boundaries of a professional sport – which is difficult enough to achieve without having to face racism. It was Ribbs’ self-belief that pulled him through, doing so with a strut that both endeared him to some and riled others.

Still, it was probably needed in a world in which he was branded “uppity n*****” by his contemporaries. Ribbs eventually managed to shut out the hatred and also became the first black man to qualify for the Indy 500, doing so in quite incredible circumstances aside from the difficulties he endured.

Getty Images

Ribbs excelled in British motor sport, but didn’t enjoy such equality when he returned to the US

Getty Images

Uppity was made by Nate Adams and Adam Carolla, the directing pair who have conceived other racing films such as Shelby American and Winning: The Racing Life of Paul Newman. Adams first ran into Ribbs when interviewing him for the latter, as Hollywood star Newman was instrumental in helping revive his stalled career. Upon interviewing Ribbs, Adams had his next film project visualised already. Looking back on Ribbs’ life, it’s hard to believe someone hadn’t made it into a film already, and the director recognised this. “The first rough cut was four and half hours long,” Adams said in conversation with US writer and reporter Marshall Pruett. “There wasn’t a lack of material, we’ll say that.”

One can imagine the both epic and episodic nature of Ribbs’ life helped the documentary to almost make itself.

As a young man, he advanced in the local San Jose motor sport scene as a black person in a predominantly white community. He then migrated to the UK to dominate the 1977 BRSCC Star of Tomorrow Formula Ford championship, before heading home to Stateside indifference. He was hounded out of NASCAR by racism, there were battles and brawls in Trans-Am, a hopeful Brabham F1 test, before finally getting Indy 500 redemption via one aborted entry (more discrimination) and six engine failures en route to an ultimately successful second attempt.

It’s a melting pot not just for a great racing documentary, but a heart-warming film with crossover appeal. It also makes Senna look like an easy ride.

Not only did Ribbs attract characters with notoriety in the motor racing realm, he also became involved with some of the world’s biggest power brokers and celebrities – personalities who are equally revered and reviled.

The young driver first caught the attention of Ecclestone when attempting to break into Formula Atlantic after his FFord triumph.

Ribbs describes being totally ignored due to the colour of his skin in the FA paddock, but nonetheless took pole at the 1982 Long Beach round by 0.2sec, ahead of a field that featured Al Unser Jr, Michael Andretti, Geoff Brabham and Roberto Moreno. He then set about dominating the race before being forced out with an engine failure. No win, but Ecclestone was present and had noted the performance.

The money ran out, but luckily Hollywood megastar Paul Newman was the next to have taken notice. The benevolent Butch Cassidy star was touched by Ribbs’ racing endeavour and pledged to help him find a paid drive in Trans-Am, finally setting him on his way as a professional racing driver.

Ribbs grabbed headlines with a tough racing technique, quick wit in interviews, and most importantly the ability to win races. But the film is not a total aggrandisement, and on occasion subtly notes his flaws – such as his tendency to rub some colleagues up the wrong way, which almost harmed Ribbs as much as his undoubted talent helped him. As a result he bounced around Trans-Am teams, never building up the head of steam needed to secure the title.

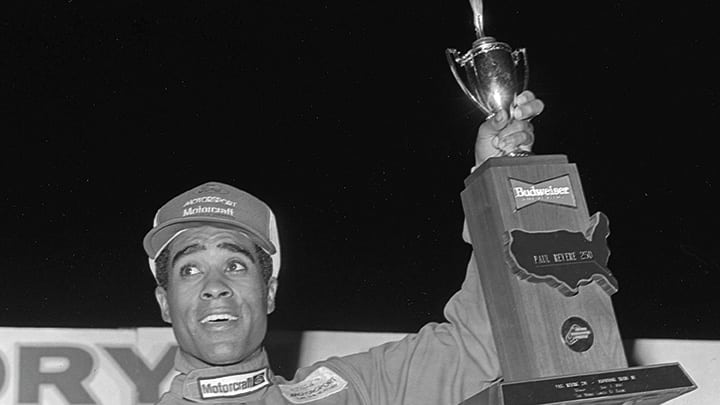

Ribbs’ victory celebration would be to jump on the roof of his 800bhp Camaro and do the ‘Ali shuffle’ emulating his boxing hero

The American’s victory celebration would be to jump on the roof of his 800bhp Camaro and do the ‘Ali shuffle’, emulating his boxing hero whom he once tracked down and jogged with on a trip to London during his FFord days.

Ribbs reveals in the film the inspiration he took from Muhammad Ali’s advice and resolve after Ali was sentenced to five years in prison (which was overturned) and then suspended from boxing due to his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War.

The next big mover and shaker to become involved in his life was coincidentally the notorious boxing promoter Don King. Noticing Ribbs at a Las Vegas Trans-Am race, King made contact. As Pruett puts it in the film, “King might have been one of the sport’s biggest scumbags, but when he calls, you take it.”

King, who wanted to make Ribbs “the Ali of auto-racing” secured backing for him to enter the 1985 Indianapolis 500. It seemed like his dream of succeeding at elite level would come true, but racial prejudice soon reared its head. It turned out that Ribbs’ chief engineer at the Brickyard was not totally sympathetic towards black people, and therefore elected not to fit the crucial windshield to the March Indycar during the Rookie Orientation test.

The result was that Ribbs’ head was almost ripped off at 170mph. Deciding it was best to call it quits rather than head out into all-out war with his own team, it seemed as if Ribbs’ Indy dream was over. It’s scenes like this that help Uppity stand apart from other sporting films.

Despite undoubted challenges in their respective lives, you don’t hear about Michael Jordan being hounded out of the Chicago Bulls for being black in The Last Dance, Pelé suffering racist abuse from his own Santos squad in his eponymous biopic or members of Sunderland football club in Sunderland ’Til I Die being hampered by their own team members simply because they were of a certain ethnicity.

While these people will likely have experienced discrimination at various points in their lives, and there are undoubtedly still problems with racism around the world in many sports, rarely will you see these issues laid out so barely and brutally as the US motor sport scene in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s in Uppity.

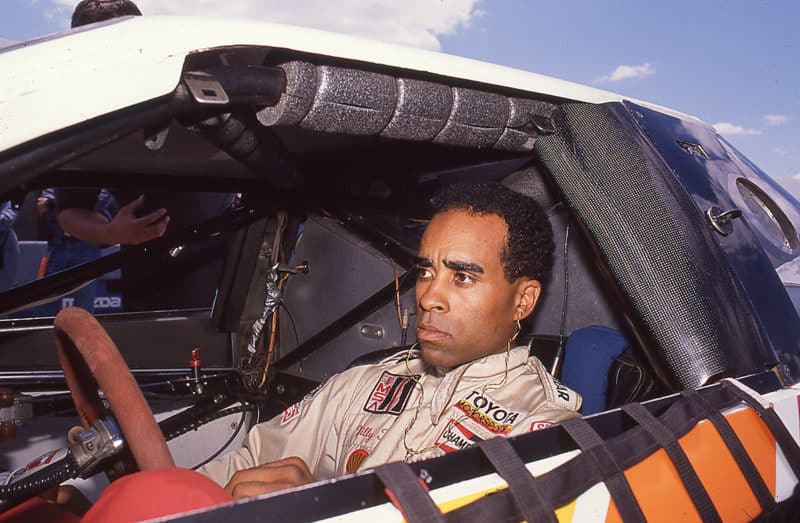

Ribbs aboard his Raynor Motorsports Indycar at Long Beach in 1990

Trans-Am brought success, such as this victory at Daytona in 1984

Getty Images

With Tom Gloy and Greg Pickett, who all drove Mercury Capris for Jack Roush Racing in 1984

Getty Images

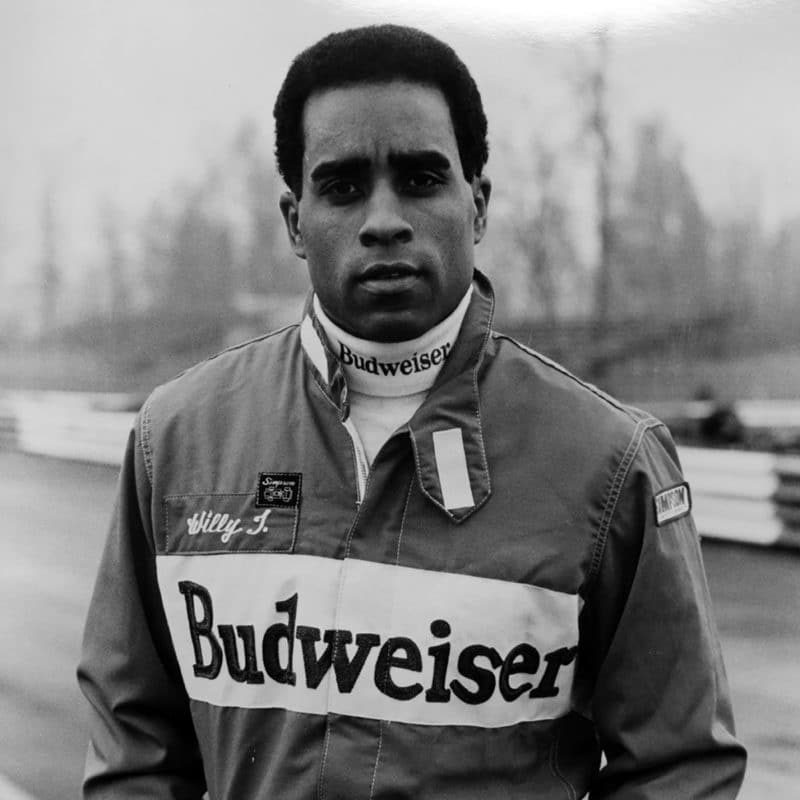

Standing proudly next to his Budweiser Racing Team Chevrolet Camaro in 1980

Ribbs’ seven-season Indycar career came to a close in 1994. He made history by qualifying for the Indy 500 in 1991

Getty Images

It is all the more credit to Willy T Ribbs that he kept fighting. Another benefactor finally came along, the disgraced then ‘un-disgraced’ comedian Bill Cosby. Despite Cosby’s immense fame at the time, corporate America wasn’t keen on funding a black driver. Cosby sponsored Ribbs himself, and via yet more mechanical high jinks and 200mph crises, Ribbs triumphantly became the first black person to qualify for the Indy 500.

The reaction to the film upon its release (it’s a streaming title on Netflix) from those close to Ribbs indicated how true to life it was in telling his powerful story, as well as sending ripples through the wider motor sport world.

“Damon Hill messaged me after seeing it,” Ribbs said in conversation with Motor Sport. “He told me he was watching it on the way to a grand prix, and ran out of tissues on the plane!”

Uppity serves as a two-fold film, showing the immense difficulties of ever making any progress in motor sport at all, but also the struggle of African-Americans against rampant and sometimes incessant racism during the latter half of the 20th century.

As racing documentaries go, you won’t find any that are more powerful than Uppity.