Grand Prix

After a series of false dawns in documenting Formula 1 in the cinema, Grand Prix promised to change the game. And, even if the film counted the sport itself among the doubters, it did just that...

GRAND PRIX

Released 1966

Director John Frankenheimer

Studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Stars James Garner, Yves Montand, Brian Bedford, Antonio Sabato

Gross $20.8m (Budget $9m)

In a parallel universe, the iconic Steve McQueen racing film could have been Grand Prix rather than Le Mans. The mercurial actor was at one point attached to John Frankenheimer’s epic, if soapy, spectacular before departing the project for reasons that have never quite been made clear.

“He’d already said that he wanted to do the picture,” recalled Frankenheimer. “We were supposed to have a meeting but I couldn’t make it so sent my producing partner Eddie Lewis.” Lewis sat down with McQueen and the two men apparently took a near-instant dislike to each other, the end result being that McQueen walked. Maybe it was because he didn’t like Lewis. Or maybe because he was in fact planning his own F1 picture (eventually abandoned to be replaced with Le Mans). Either way, Frankenheimer was hugely disappointed. Less so, McQueen’s next door neighbour James Garner, who took over the role of American driver Pete Aron (loosely based on Phil Hill).

“I don’t think John wanted me,” observed Garner in his typically wry way. “I don’t think he wanted anyone with an opinion! But the studio wanted me so he went along with it. And making Grand Prix turned out to be just about the most fun I ever had on a movie. It was a high point in my film career. So I owe that to Steve turning it down.”

Unlike McQueen, Garner did not come to the project with a reputation for racing. But he had been interested in motor sport as a youth and was to discover he had a natural aptitude for driving. Former Shelby and Ferrari legend Bob Bondurant was hired as technical consultant for the film and was asked to accompany each of the main cast in a two-seater version of an F1 racer, to see how they would cope with the speeds. He noted that all but one of the actors grew increasingly uncomfortable and frightened once the speedometer reached around 150mph. The exception was Garner, who would return to the pit grinning like a Cheshire Cat.

Garner put in a starring performance, both on camera and behind the wheel. Here his character, Pete Aron, celebrates victory in the Italian Grand Prix

Getty Images

“That’s your man,” noted Bondurant. Garner would go on to do pretty much all his own driving in the film and Bondurant even suggested the actor was probably good enough to beat some of the actual F1 drivers of the day. Garner’s natural talent was a major boon to Frankenheimer, who wanted to use stunt drivers as little as possible in his hunt to give audiences a more authentic experience of racing than cinema had managed before. That meant filming real racing under real conditions, even if the F1 community was not initially very welcoming.

“We’d never seen a racing film that meant anything to the drivers,” said Jack Brabham. And it was true that up until then, Hollywood’s idea of a racing picture usually involved shooting a car in front of an unconvincing rear projection.

“Everyone was very sceptical about another Hollywood movie on racing,” admitted Frankenheimer. “To the point where Ferrari actively wanted nothing at all to do with it. They even told us we couldn’t use the word ‘Ferrari’ in our film.”

The director eventually won Ferrari – and the other teams – over by temporarily halting production in order to edit together a 30-minute reel of detailed footage he’d captured in Monte Carlo. The footage – astonishing, exciting, and immersive – was like no Hollywood movie up to that point. It promised a film that could offer viewers a real experience of racing and race day.

The quality of the reel earned the filmmakers unprecedented access for the rest of the shoot. Ferrari allowed the crew inside its production floor and up close with the race day cars and many drivers agreed to appear in the film, including six world champions: Phil Hill, Graham Hill, Juan Manuel Fangio, Jim Clark, Jochen Rindt and Jack Brabham.

The final film also included some of the earliest experimentation with in-car cameras for F1, particularly in terms of POV shots that would allow audiences to imagine themselves in the driver’s seat. Phil Hill even drove a modified camera car in some sessions during the actual grands prix. The combination of real-life race footage and the spectacular movie footage shot on location (with Formula 3 cars mocked up to look like F1 models) would go on to influence pretty much every racing film ever made since.

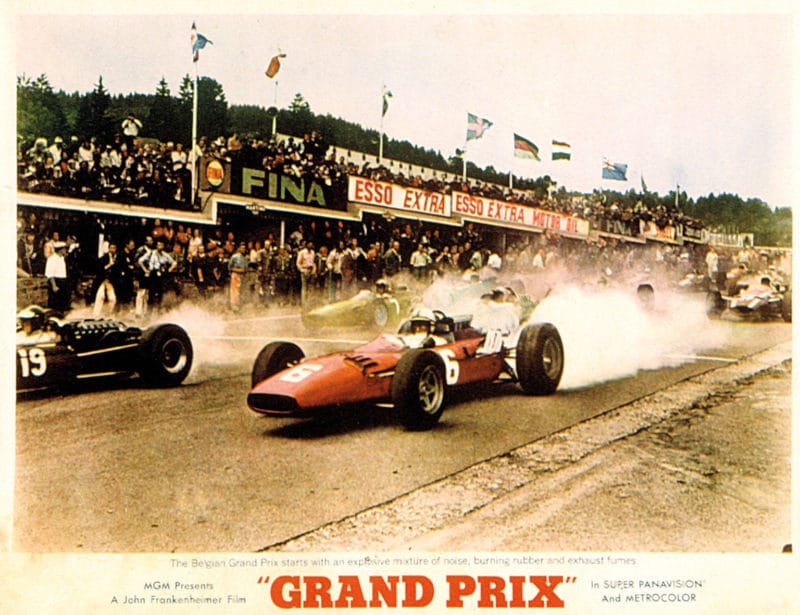

In the quest for authenticity, Grand Prix did its shooting at many actual races, recreating scenes on location

As Peter Yeats, director of Bullitt, observed: “Frankenheimer had a reputation for always doing things in the most difficult way possible but that was because he was always after realism. And with Grand Prix you see the result of that quest: as you’re watching you have this feeling of it actually happening. It’s why I don’t think the film really dates.”

“The crowds are real… as is the excitement!” declared a promotional piece made at the time of filming that shows Frankenheimer’s crew and cast mingling on the streets of Monaco on race day, wheeling their Super Panavision cameras past the palm trees and impossibly stylish artefacts of the times – cars, yachts, helicopters, sunglasses-wearing jet setters and bohemian locals with jumpers draped over slim shoulders, leaning on stunningly beautiful sports cars. Throughout the promo, every street is crowded with noise and colour and movie stars – Yves Montand, Françoise Hardy, Eva Marie Saint, Garner (who at one point gets into a row with a local shopkeeper trying to fleece the crew out of more money) – while Frankenheimer, his dark hair slicked back a la Elvis, prowls around intensely, occasionally looking like he’s about to erupt (he was a serial swearer on set). The camera operator, John M Stephens could often be seen precariously hanging out of a helicopter to capture aerial shots (“It was the most exciting motion picture I ever worked on.”) and all the crew eagerly utilised any colours and sounds available to them – when Jackie Stewart celebrated his victory, they capture Montand mirroring the celebrations for the movie. The line between reality and fiction at times got blurred.

The crew would even shoot around real accidents to create more footage. (Though for the film’s more spectacular crashes, they would use hydrogen cannons to fire cars through the air with dummies in the driver’s seat). There’s a point in the finished film where Garner appears to be on fire. It’s not a special effect. He did indeed catch light as the crew scrambled to put him out.

“The insurance company cancelled my insurance after that,” recalled Garner, who shot the final month of the film uninsured. It’s an astonishing way to make a movie and probably impossible to replicate today as F1 is simply too polished, too commercial and too controlled to allow a crew the same levels of access or the same opportunities for happy accidents. But in 1966 Frankenheimer managed to corral 205 people and 65 race cars across nine countries in order to capture the feel of a real season.

“I don’t know how we did it,” admitted Garner decades later. “You’d have to hand it to Frankenheimer. He pushed people to their limits to get it done. We got as close as you could get, at that time, to what racing is all about.”

At first, Formula 1 teams were dubious and unwelcoming to the production crew, but after they saw some B-roll, many were only too happy to get involved in the project

Getty Images

Of course, the finished film isn’t just a racing travelogue. Grand Prix’s three-hour runtime also includes oodles of angsty and existential drama to create a proper old school Hollywood melodrama. Frankenheimer didn’t just want to capture the feel of a race. He wanted to capture the feeling of a whole season. Hence Grand Prix’s array of colourful characters.

There’s Garner’s Pete Aron, hot-headed and reckless but given a chance to step up from also-ran status when he signs for an ambitious new team (run by Akira Kurosawa regular Toshiro Mifune). Aron’s main rivals are Antonio Sabàto’s brash young Italian wannabe Nino Barlini, Brian Bedford’s troubled Brit Scott Stoddard and (arguably the film’s lead) Yves Montand’s Jean-Pierre Sarti, an ageing two-time world champion now growing increasingly cynical about the sport. There’s also ‘The Women Who Love Them’.

Namely, Eva Marie Saint as roaming reporter Louise Frederickson who is covering the season and falling for Sarti. Geneviéve Page as Mrs Sarti, the wife who doesn’t really want her husband… but won’t let anyone else have him. Françoise Hardy as Lisa, a free-spirit who dallies with Nino though both of them are too young and pretty to take it very seriously. And finally, the wonderful Jessica Walter as Stoddard’s unhappy wife who makes a play for Pete Aron.

Walter offers probably the best performance in the film, full of nuance, layers and grounded feelings that the film isn’t really interested in exploring. It just wants to get back to the track…

But what is F1 if not sport’s best soap?

Especially in the 1960s. When the jet-setting glamour of it all was something most folk could only visit in the inky text and black and white photos of a newspaper. Unsurprisingly, Grand Prix was a hit at the box office – the sixth biggest film of the year. Even Steve McQueen went to see it… eventually.

“I was driving home one day,” recalled Garner. “It was about a year after Grand Prix first came out and apparently Steve’s son Chad had finally forced him to take him to the cinema to see it. I pulled up and saw Steve and he said, ‘Well, we went to your movie…’ I said, ‘Oh yeah? What did you think?’ And he kind of shrugged and said, ‘Yeah… it was pretty good.’ And that was as much as I got out of him about it!”