Reliving the glory: Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks' victory at 1957 British grand prix - race report

In this 1957 race report, Denis Jenkinson saw Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks take victory at the British – and European – Grand Prix at Aintree. He lauds Stirling’s relaxed racing style, in contrast with his rivals’ ‘clenched-teeth’ efforts, and the achievement of home-grown manufacturer Vanwall

The English motor-racing scene suffers from a split personality just as the French one does, for whereas France alternates between Rouen and Reims for its National Grande Epreuve, England alternates between Silverstone and Aintree. This year it was the turn of the Northern circuit to hold the British Grand Prix and, for what it was worth, it was also given the title of the European Grand Prix. This is a rather pointless title which carries no significance with it and is given to one of the major grand prix races in the world championship each year by the FIA and allows the organisers to pretend that their event is the most important of the season. In actual fact all world championship events carry equal status.

It was rather remarkable that, after running in a full-length grands prix for the previous two weekends, the major teams were all ready on the first afternoon of practice at Aintree, which was on the Thursday before the race. The Vanwall team was the first to start practice on the rather damp track, and it had all three entries out, being driven by Moss, Brooks and Lewis-Evans, the No1 driver having recovered from his bout of sinus trouble, Brooks being fit again after his Le Mans accident, and the new boy, Lewis-Evans, fresh from his excellent drive at Reims, while the cars were well turned out, as always. The Maserati team comprised Fangio, Behra, Schell and Menditeguy, and all four were using six-cylinder cars, the 12-cylinder being left at Modena after its poor showing at Rouen and Reims. The Scuderia Ferrari had four Lancia/Ferrari cars out, driven by Collins, Hawthorn, Musso and Trintignant, and the BRM team had two, driven by Fairman and Leston.

As is a regular sight at GP meetings now, John Cooper had two of his Formula 2 cars running, fitted with Coventry-Climax twin-cam engines, and these were in the hands of Salvadori and Brabham. To complete the field for the first practice day there were the two privately-owned Maseratis of Gould and Gilby Engineering, the latter driven by Bueb.

Moss presses on after taking over Brooks’ car. In truth, the latter really shouldn’t have been driving at Aintree so soon after his crash at Le Mans. He had a huge hole in his leg and could barely clamber from the car when he pitted for Moss to replace him

The Vanwall team set the pace and Moss tried all three cars, making his best lap with Brooks’ car and only just beating Lewis-Evans in the same car, while Brooks was content to feel his way back into fast driving, still being sore after his accident. The Maserati team was soon having a go at the Vanwall standard and, surprisingly, it was Behra who was fastest, using Fangio’s car, which was No2, while on No4, which was Behra’s car, Fangio was fastest. The Ferrari team was also juggling about with its four cars, all the drivers trying all the cars except Musso, who stuck to his own car and did not let anyone else drive it. For no apparent reason Trintignant had been allocated the fastest car, and as soon as this was discovered it was taken away from him and given to Hawthorn. In spite of this none of the Maranello drivers could get among the times recorded by the Vanwalls and the Maseratis, and the Ferrari team was not looking happy. The two BRM drivers were quite unspectacular, which was to be expected as neither of them had driven the cars before and were both using the first practice session to get accustomed to them.

It was interesting to see that the Vanwall team tried a car on Dunlop tyres in place of Pirellis, for since the Italian firm has stopped making racing tyres the Pirelli stocks for Vanwall and Maserati have been getting low. A Pirelli racing tyre is now becoming worth its weight in gold, and to see one of the Vanwall cars on Dunlop was a sign of the times. BRM, which has always used Dunlop’s racing tyres, was experimenting with different tread patterns front and rear to effect small changes in handling characteristics, and with the coil springs front and back, as used at Rouen, the cars were handling a lot better, but had nothing like as much ‘steam’ as they had last year, though this power drop had improved the reliability.

Throughout practice the loudspeaker system did not operate and no times were released from the timekeepers until practice was finished, so that it was not possible to watch the improvements during the afternoon, apart from unofficial hand-timing checks. This complete silence in the pit area and around the circuit made a strange contrast with continental races, where every fast lap is immediately announced; this tends to encourage drivers to try harder in the battle for grid positions. As if this was not enough the Northern rains came in a big way just as practice finished and the whole stadium disappeared under a cloudburst. When the air cleared and the timekeepers issued official times it was found that Behra had equalled the existing lap record with a time of 2min 00.4sec, this record having been set by Moss in 1955 with the Mercedes W196. Fangio was next fastest with 2min 01.0sec, which he recorded twice, using his own car and Behra’s car, and Moss was next with 2min 01.4sec using Brooks’ car.

The British timekeepers had done a good job of work, unlike many continental timekeepers, for they had carefully noted when a driver took out a car with another driver’s number on it, for all three major teams were shuffling their cars and drivers about. Usually this leads to chaos, in which the timekeepers say “Car number so-and-so has made fastest lap, but we do not know who was driving it.” The BARC deserve a pat on the back for providing an intelligent spotter to sort out the drivers and numbers. It would be far better if the FIA were to step in and prevent this chopping and changing, for if it is not watched it can lead to an entirely false starting grid.

“Push!” Stirling barks the order as Vanwall’s mechanics shove him away from the pits. Once settled into Brooks’ car, he rejoined the race in ninth position with a single ambition: to retake the lead he had first claimed on the opening lap in his own Vanwall

Friday practice saw the weather much better and the track dry, but a strong headwind blowing along the straight prevented any fast laps being recorded. Everyone was out again, the Vanwall team bringing out another car for Moss and relegating his Thursday car to the position of spare, all four Vanwalls being in the pits and in use. Additions to the list of runners were Bonnier with the ex-Simon Maserati and Gerard with his own version of a Grand Prix Cooper, this being a modified Formula 2 car with a Bristol engine squeezed into the rear. From the previous day it was obvious that the Maseratis and Vanwalls were most suited to the flat and uninspiring Aintree circuit, so a wander round the infield was made to observe the cars in action. Without doubt the Maseratis were the easiest cars for the drivers to get round the corners, these well-balanced six-cylinders appearing to enjoy being slid round the bends in powerslides with the rear wheels well out of line with the front ones. This meant that they left the corners on full power, even though they were on full opposite lock, and with so many stop-and-start corners their handling was giving them a definite advantage. Even on the fairly fast Waterway Corner after the pits, this tail-sliding technique seemed to pay. The Vanwalls, on the other hand, had very neutral-looking characteristics and the power could be fed in progressively as the corner unwound, there being just a small degree of understeer visible. Pick-up from the middle rev range was not too clean and they made up with speed on the straight for what they lost in the corners. Not only were the Vanwalls going fast down the straight, but a full side view at 160mph, from a distance, gave an excellent impression of the aerodynamic shape of the cars. The Lancia/Ferraris were, comparatively, in an unhappy state, for they had a high degree of understeer and if the drivers turned the power on too early in the corner there was a tendency to push the front of the car off the original line, which meant power had to be taken off. Hawthorn was really trying and showing the perfect way to drive the 1957 Lancia/Ferrari, braking late and hard going into the corners, taking the bend on a neutral throttle and then giving it full power. The two BRMs were also suffering from too much understeer and any application of power was tending to push the front end off- line, Fairman going round on a smooth throttle control and Leston, jabbing at the throttle three or four times through the corner, looking rather jerky and untidy, but faster than Fairman, nevertheless. Both cars were unhappy with their brakes and had unpredictable snatching and locking, this bother eventually putting Fairman well and truly on the grass at Anchor Crossing. The little Coopers of Salvadori and Brabham showed no consistency about their method of cornering, seemingly being adaptable to the driver’s requirements. Brabham in particular seemed happily able to make the car over- or understeer according to his wishes and the speed at which he arrived at the corner. Early application of power after braking would push the car towards the outside of the corner with the driver applying more lock, while if needs be the car could be tweaked sideways in a full-opposite-lock power slide through the corner. On one occasion Brabham was enjoying himself in a power slide when the little car got the better of him and spun, but the Australian continued unabashed, merely giving the marshals a sly grin. Fangio never looked confident and gave the air of not liking the circuit.

On a number of occasions during this practice period a strange occurrence happened, for Parnell appeared in an Aston Martin DB3S with a passenger wielding a movie camera and proceeded to motor round amongst the grand prix cars. While he did his best to keep out of the way, there was no arguing the fact that he was causing an obstruction which must have made drivers over-cautious, and one wondered whether this was serious grand prix practice for the Grand Prix of Europe, or the grand prix drivers playing at film stars. No one minds a bit of fake filming when practice is finished, but to obstruct the course with a camera car in the middle of the official practice session seemed to be against the general idea of grand prix racing. The fact that the Aston Martin was flying a white flag, which usually indicates an ambulance on the course, was also strange.

Before the afternoon ended Brooks had equalled Behra’s time of the day before and Moss had broken the record by two tenths of a second; Behra, Fangio and Collins all tried hard to beat the Vanwall right up to the end of the allotted time, but to no avail. With Moss recording 2min 00.2sec and Brooks 2min 00.4sec, the practice finished with two green Vanwalls on the front row, along with Behra, and the most unusual situation of Fangio relegated to the second row.

The morning of race day, Saturday, July 20, saw rain and wind lashing the Aintree Stadium and the mechanics huddled in the transporters, while cars sat silent under waterproof sheets, and the outlook was grey and gloomy. However, around lunch-time the rain stopped, a wind dried the track very quickly, and by 2pm, when the cars assembled on the grid, conditions were not too bad. It was a fine sight to see the Vanwalls of Moss and Brooks on the front row of the grid, one on each side of the Maserati of Behra, while behind sat Fangio and Hawthorn, followed in row three by Lewis-Evans with the third Vanwall, Schell (Maserati) and Collins (Lancia/Ferrari), he having changed cars with Hawthorn at the last moment. In row four sat two more cars from the Rampant Horse stable, driven by Trintignant and Musso, in row five came Menditeguy (Maserati), Leston (BRM) and Brabham (Cooper), then Salvadori with the other works Cooper, on his own as Gould was a non-starter due to a foot injury, quite unconnected with driving; in row seven were Fairman with the other BRM, Bonnier’s old Maserati, and Gerard in the rear-engined Cooper-Bristol that had trouble in practice with carburettor fires, and right at the back on his own sat Bueb in the Syd Greene Maserati, having missed the Friday practice due to a broken piston on the first day. Unlike some recent grand prix starts, this one was perfection, everyone being ready when the flag was raised and the track clear of mechanics and equipment. In spite of some tyre-burning wheelspin Behra got off the line first and led away down to Waterway Corner, but before halfway round the first lap Moss had got the Vanwall into the lead. The end of the opening lap saw a very tightly packed follow-my-leader round Tatts Corner into the pits straight, in the order Moss, Behra, Brooks, Hawthorn, Collins, Schell, Musso, Fangio and the rest, with Bueb bringing up the rear.

The teardrop VW5 came of age at Aintree. Underpinned by a chassis penned by a promising young designer called Colin Chapman and styled by aerodynamicist Frank Costin, the Vanwall would now prove the class of the field in ’57 – even if Fangio still won the title for Maserati

Having got the lead, Moss did not mean to waste time and drew away from Behra, while Brooks and Hawthorn battled for third, the Lancia/Ferrari gaining the advantage round the corners in mid-field and the Vanwall whistling by on the Railway Straight. After five laps Brooks realised he was not fully recovered, his leg still being stiff, and he eased up, letting Hawthorn safely into third behind Moss and Behra, while Collins began to close on the second Vanwall. Fangio was nowhere in the running and Musso soon caught him and went by and then Lewis-Evans got into his stride and went by the world champion and the first bunch of 10 works cars were now evenly spread out, with the Vanwall of Moss way out in the lead. At the back Leston was holding up the two Coopers, and first Salvadori had to fight his way by, and then Brabham, it being noticeable that once the rear-engined cars had got past they left the BRM behind. Fairman was a long way back and was in company with Bonnier, Gerard and Bueb, though the last of the quartet did not keep going for long and stopped at the pits to change plugs.

By 10 laps Moss had settled down to a lead of 7½sec over Behra and was looking relaxed, while Hawthorn had his teeth clenched and his chin jutting forward as he was having a go at Behra for second. Brooks was now being attacked by Musso, but the next lap the Italian had a moment on one of the corners and lost ground, dropping behind Lewis-Evans and Fangio. The leading Vanwall had already started to lap the tail-enders and by lap 20 the lead was 9sec, so that once more the Vanwall was showing everyone that it was the latest grand prix car, and Moss was demonstrating that he had fully recovered from his illness. The second position was still open between Behra and Hawthorn, and these two were the only ones in Italian cars who could be considered to be motor racing, for Collins was not keeping his end up, Fangio was only just in the picture, and Schell, Menditeguy and Trintignant were way at the back of the major runners. Having shaken themselves clear of the BRM, Salvadori and Brabham were hanging on to the tail of the Italian cars, it being obvious that Trintignant was not going to be able to stay ahead of the Coopers much longer.

At the end of the 21st lap the sun began to shine, but not in the Vanwall pit, for Moss went by with an unmistakable falter in the exhaust note of his car and Behra was now only 7½sec behind. The next lap Vanwall hopes sank to bottom for Moss headed for the pits, thinking that perhaps the magneto switch might be faulty. In a matter of seconds the mechanics lifted the bonnet and ripped the magneto earthing wire off, and Moss rejoined the race, but not before Behra, Hawthorn, Collins, Lewis-Evans, Brooks and Musso had gone by, in that order. The trouble to the Vanwall was, however, much more serious, and at the end of the next lap Moss stopped again, the misfire not being traceable, possibly being due to misadjustment of the mixture or some internal fault in the engine. There being no cure for it, Brooks was flagged to come in and hand his car over to Moss, for he had made it clear before the start that he did not think he could keep going for the whole 90 laps but would do his best to keep his Vanwall “nicely on the boil” in case one of his team-mates should need it. That need now arose and Moss took over on lap 26, starting off in ninth position.

This high drama amongst the leaders rather overshadowed the fact that Salvadori had got his little Cooper past Trintignant’s Lancia/Ferrari and there was nothing the Frenchman could do about it. Schell now came into the pits with a steaming radiator, and this immediately let Moss into eighth place, driving the Brooks Vanwall, while Lewis-Evans was holding a very neat and confident fourth place and beginning to close on Collins. The lead was still in the hands of Behra, who was driving in a very polished style, and he had drawn a few seconds ahead of Hawthorn, so that he was firmly in command of the race. However, Moss had other ideas, and first he went by Menditeguy without any trouble at all, and then closed on Fangio, setting up fastest laps in the process. By lap 35 Moss had got by Fangio and the Vanwall was really being thrashed round the circuit in a win-or-bust effort, the Maserati pit getting very worried about the closing gap, in spite of the fact that there were four cars between Behra and Moss.

Dirty work: panda eyes tell the tale for Britain’s hard-working winners. The Aintree race also carried the title of Grand Prix d’Europe – but Jenks considered that meaningless

The Lancia/Ferrari of Collins now began to show signs of sickness, and Lewis-Evans closed up rapidly, while Menditeguy retired at the pits with a badly vibrating propshaft, due to a crack in the tube, and Schell was now boiling merrily for his water pump had broken. Brooks had restarted in the sick Moss car and was circulating at the back of the field, but having a miserable ride for the misfire was getting consistently worse.

The leading Maserati was sounding perfect and staying nicely ahead of Hawthorn’s Lancia/Ferrari even though the Englishman was well on form and driving with his forceful manner, and Collins was having yet another bad day, for his car was losing power and Lewis-Evans took third place from him. Moss dealt with Musso as quickly as he had with Fangio, and his next objective was the ailing Collins, but it now seemed unlikely that he would be able to catch Behra, for half-distance was approaching and he was a whole minute behind.

Schell retired at the pits with his very overheated Maserati, and the Salvadori-Trintignant battle continued unabated. Brabham followed them, still ahead of the two BRMs, and Gerard and Brooks were bringing up the rear, Bonnier having retired and Bueb having made so many stops with the sick Maserati that he was nowhere in the running. At 45 laps, exactly half-distance, a gap of 9sec separated Behra and Hawthorn, then came Lewis-Evans driving a beautifully steady race, 20sec behind the Lancia/Ferrari, and then 21sec later came Collins, with Moss about to overtake him, which he actually did two laps later, thus moving into fourth position, behind his young team-mate. At this juncture Leston blew up his engine and retired at the pits, and only three laps more saw Fairman retire with the other BRM, a trail of vapour from the exhaust rather indicating internal maladies in the engine. Neither car had shown any speed capabilities and they had now lost reliability as well. On lap 49 Fangio coasted into the pits with broken valve gear and on lap 53 Collins went out with a water leak, so that the field suddenly became rather sparse. Aware that Moss was still pressing hard, Behra equalled the lap record, but Moss countered this by breaking the lap record well and truly, doing it again a little later and reducing the gap between the Vanwall and the Maserati to 45sec. Hawthorn was continuing at his same speed, so that Behra’s added speed increased his lead over the second man, and it was now an easy matter to calculate just when Moss was going to overhaul Hawthorn and take second position. With Collins at the pits and Trintignant still unable to deal with Salvadori, the Frenchman was called in and Collins took over. However, three laps later Collins came back into the pits and gave the car back to Trintignant, it obviously not being to his liking.

A straight arm shoots for the heavens as Stirling scores another famous Aintree win. His first British GP victory in 1955 was also the first for a British driver on home soil in the post-war era. But that had come in a silver German car – this time he was sporting British Racing Green…

By lap 65 the two Vanwalls were closing rapidly on Hawthorn and the Behra to Moss gap was down to 36sec, which was reduced yet again when Moss got the lap record down to 1min 59.2sec. Musso, who was in fifth position, was now lapped by Behra, and Hawthorn, Lewis-Evans and Moss were in close formation, with second position available to all three. As they started the 69th lap Behra had a 22sec lead and Hawthorn, Lewis-Evans and Moss went by as quickly as that, but half-way round the lap everything happened at once. Moss was about to overtake Lewis-Evans anyway, when Behra’s crankshaft or clutch/flywheel assembly, it was never quite sure which went first, flew apart and he slowed right down. Hawthorn was following and before he could take the lead he ran over some of the fragments of the burst Maserati and punctured his left rear tyre, so that Lewis-Evans went by into the lead, but at that precise moment Moss was about to pass his team-mate, so that the two Vanwalls came down the straight towards the Melling Crossing, with Moss first and Lewis-Evans second, followed by Behra coasting in to retire and Hawthorn limping along on a flat tyre. The cheers that broke out all round the circuit as the two Vanwalls ran round in close company, with the opposition thoroughly defeated, were wonderful to hear, and at a signal from Moss the two cars slowed down to lap at around 2min 10sec. There was now no opposition at all, for Musso was nearly a whole lap behind and though Hawthorn had had his punctured tyre changed, he was too far away to be a serious menace.

With 20 laps to go it seemed that all the two green cars had to do was to tour in to a magnificent victory but fate thought otherwise, and on lap 73 Moss came round on his own. Lewis-Evans had stopped out on the circuit and was seen working on the engine, and a groan went up when it was announced that a ball-joint on the throttle linkage had come adrift. This was a joint that had never given trouble in the past, and its failure was no reflection on the design layout; this really was one of those strokes of ill-luck that attack the best-prepared cars. Moss was now on his own, nearly a minute and a half ahead of Musso, who in turn was about a minute ahead of Hawthorn. Behind came Salvadori, still ahead of Trintignant, and Brabham was lying sixth, but then his clutch flew apart and he retired, leaving Gerard sixth a long way behind, and Bueb seventh in the Gilby Maserati that sometimes sounded healthy and sometimes sounded about to blow up.

After the deception of Lewis-Evans falling by the wayside just when the Vanwalls were certain of first and second places, everyone kept their fingers crossed for the last 15 laps, but Moss made no mistakes and, lapping confidently, stayed out ahead of the field. As a precaution, and having some time in hand, he stopped on lap 79 and took on 10 gallons of fuel; he was still 40sec ahead of Musso when he rejoined the race.

As Moss was on his 80th lap Lewis-Evans reappeared, driving without a bonnet on the Vanwall, and after stopping at the pits to have his temporary repair made more secure he rejoined the race, going as well as ever, but now in seventh. The third Vanwall had been withdrawn long since, for it showed signs of breaking up, and rather than run the engine to death Brooks stopped. On lap 82 Salvadori stopped for fuel but the Cooper was making a ticking noise, and two laps later the gearbox casing split. After a spirited drive Salvadori limped round to the finishing line and waited for Moss to complete the 90 laps so that he could push the Cooper in to finish.

With a feeling of relief that could be felt all round the circuit Moss crossed the line to win the first Grande Epreuve for Vanwall, a happening that was bound to come sooner or later, and it was very fitting that the climax of all Mr Vandervell’s efforts should be achieved in the British Grand Prix.

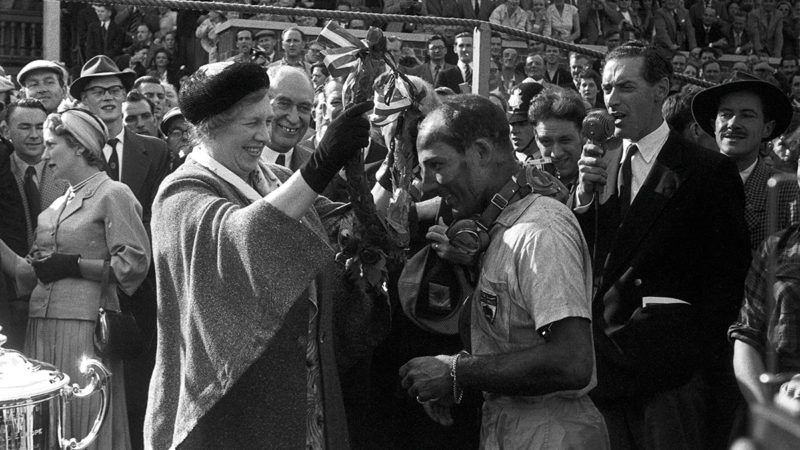

Moss accepts the laurels from Aintree chairman Mrs Topham. He’d completed 90 laps of Aintree in 3hr 6min 37.8sec at an average speed of 86.80mph, and also claimed the fastest lap. But after victories in Argentina, Monaco and France, Fangio was in touching distance of what would be his fifth title

Once the chequered flag had fallen enthusiasm for this hard-fought victory knew no bounds, and the crowds flooded on the track to acclaim the greatest British victory of all time, one which was achieved against the strongest possible opposition in a race that had put the greatest stress on mechanical endurance as well as on driver skill. The three Lancia/Ferraris of Musso, Hawthorn and Trintignant filled the next three places and Salvadori, Gerard, Lewis-Evans and Bueb brought up the rear.

Not since the Italian Grand Prix of last year had a race been run where such mechanical misfortune, bad luck and the unknown quantity played such a big part. But through it all, having had their own fair share of drama, Moss driving Brooks’ Vanwall had triumphed, and everyone paid tribute to Mr Tony Vandervell for getting together the team of drivers, mechanics and technicians that made it possible for a thoroughbred British car to win the British Grand Prix.