Chapter 2: Unveiling Stirling Moss' early years and the making of a single-seater legend

Learning his craft in 500cc F3 cars and honing it in F2, Moss became a single-seater specialist with a sixth sense and a driving ambition that took him far from England’s shores and deep into the spiritual home of racing

This prototype modern professional racing driver proved the efficacy of Britain’s blueprint for progression within a junior formulae structure. The 500cc bike-engined Formula 3 buzz bombs – with their obvious link to the pre-war appetite for sparse hillclimb/sprint specials – were an austerity product: simple, frugal and (relatively) cheap. The ‘karting’ for a formative Moss, he raced them until long after he had become an established name, for he reckoned rightly that the category’s emphasis on maintaining momentum within its swirling cut and thrust kept him sharp.

They stood him in good stead in another way, too. His bespoke Kieft of 1951-52 was in the vanguard of variable suspension set-ups for differing circuits. A stable understeerer, it enabled him to brake later and carry more speed, in the manner of the Formula 1 of some 10 years hence. Only following Fangio taught him more.

Formula 2, in contrast, was not a British construct, but it allowed its constructors/teams with more moxie than money – Connaught, Cooper and HWM, etc – to visit the Continental spiritual home of motor racing, as well as tackle the undulating, constant-radius perimeter roads of its local bomber base tracks: trickier than they looked and handily more forgiving of mistakes, the latter were another British blueprint for the sport’s future look; and another long-term benefit for Moss.

Moss the buccaneer was in no mood to wait and see, however, and he jumped at the chance to fly the UK nest in 1950 with HWM, to learn the black arts that gave the more experienced Alfa Romeo, Ferrari and Maserati their advantage. He drove quickly enough to invoke world champion-elect Giuseppe Farina’s ire – much to the amusement of the following Fangio – and to hurt himself when HWM’s build quality wilted under the strain he imposed. He was making a name for himself – and had caught Enzo’s eye.

Rising star: 18-year-old Moss tackles Prescott at the wheel of a Cooper-JAP in May 1948 – his first attempt at a hill climb event. He went on to finish fourth in class and would carry on competing in 500cc Formula 3 cars until 1954

Moss was right up Ferrari’s strada: an acrobatic risk-taker with a sixth sense, he was the new Nuvolari. Yet they would fall out when the youngster was left high and dry and embarrassed at the Bari GP of 1951. He would never forget – and would only forgive some 10 years later – his shoddy treatment by an apparently unrepentant Commendatore: the F2 car promised him had been awarded to another at the eleventh hour. This was a knockback: Moss should have been picking low-dangling fruit aboard that now dominant Ferrari 500, as a struggling world championship turned to F2; instead he was waylaid by that fruitless (at the time) search for a British winner. It did, however, wise him up: the swirling cut-and-thrust did not end at the track’s edge.

Though he loved beating Ferraris most of all, born winner Moss hardly ever lacked for motivation. His off days were as rare as hen’s teeth, as were his days off. F2 would remain integral to a crammed diary until that enforced retirement, and bring him success with Porsche and Borgward’s fuel-injected engine. Non-championship F1 races abounded and often were world championship events in all but name; and he gave them his all. The big-engined Cooper built for 1961’s short-lived InterContinental rival to the ‘Dinky’ 1.5-litre F1 was one of Moss’ favourites – he lapped the entire field with it at a wet Silverstone – and the quirks of the four-wheel-drive Ferguson P99 fascinated him; total traction’s ultimately underwhelming story in F1 might have been more upbeat had his insightful and inspirational input not been so brutally interrupted.

The only glaring gap in his single-seater CV was Indianapolis. Moss, though indisputably fond of a bob or two, eschewed the big bucks on offer Stateside and was unusually uninformed about The Brickyard: its contestants only turned left and didn’t race in the rain. He couldn’t resist showing America’s best what was what at the 1958 Race of Two Worlds on Monza’s bankings. Venturing out during wet practice, he almost crashed. He would discover, too, that there was more to oval racing than straight-line grunt; the Indy roadsters eked their edge over his Maserati-based special on those perilous bankings. And it was tough work, the high g loadings breaking his steering and causing him the scariest accident of his career – bar one.

The Americans had earned his respect – and he theirs – but still he shunned the 500. True, trans-Atlantic jet travel was in its infancy, and May was a crunch point in the European season, but the sport’s superstar could have found room. Given all of the above (and below) – the numerous and various challenges offered, accepted, met and dispatched – it’s surprising that he never would be so minded.

- Moss receives a ‘good luck’ handshake from former Brooklands racer father Alfred at the inaugural Silverstone meeting on October 2, 1948. He led the 500cc F3 race that served as curtain-raiser to the RAC International Grand Prix, but was forced to pull off after his engine sprocket worked loose, gifting victory to rival Spike Rhiando, the man who tried to introduce US-style midget racing to the UK

- Moss began to venture farther afield in 1949 – a hint of things to come in the very near future – though a trip to contest May’s Manx Cup required only a short flit across the Irish Sea. Six weeks later he travelled to Garda, Italy, to contest his first true overseas event, driving a Cooper-JAP 1000 MkIII. Not only did he last the distance, he continued his upward momentum by taking a class-winning third overall

- Moss flirts with the natural street furniture on the Douglas road course during the 1949 Manx Cup. He led the race in his Cooper-JAP but was eventually forced to retire

- in July 1949, seven months after his fine drive at the UK’s first post-war grand prix meeting, Moss recorded his first victory at a British GP in the 500cc F3 support race. He is pictured with his parents before the start

- Moss adorned with the victory spoils after adding to his collection of F3 wins – first time out with a Kieft – at Goodwood in 1951

- The Kieft had a variable suspension set-up that was advanced by the standards of the day, a detail that helped him refine his driving technique. Only following team-mate Juan Manuel Fangio during 1955 would teach him more about his chosen craft…

- Paula Cooper, wife of John Cooper, congratulates Moss at Silverstone in August 1950 – and with good cause. Pre-race clutch trouble caused him to start at the back of a 32-strong field, yet he was up to third by the end of the opening lap and took the lead on the second before romping home to victory. Rivals vanquished that day included fellow young gun Peter Collins

- Formula 2 duty at Crystal Palace. John Cooper smiles for the camera while Moss chats before the start of the 1953 Coronation Trophy, in which he took his Alta-engined Cooper T24 Special to fourth place in his qualifying heat and fifth in the final. The race was won by Connaught driver Tony Rolt, one of the men behind the 4WD Ferguson P99 F1 car, which Moss subsequently raced

- It would be unthinkable nowadays for a driver to continue in F3 after graduating to higher categories, but to Moss it was another potential income stream. He is pictured in his Kieft at Brands Hatch in 1952, a season during which his extraordinary commitment was abundantly clear. After scoring a fortuitous win in the British GP support race at Silverstone on July 19 – and competing in the GP – he did an overnight flit to Namur, Belgium, to contest yet another F3 event

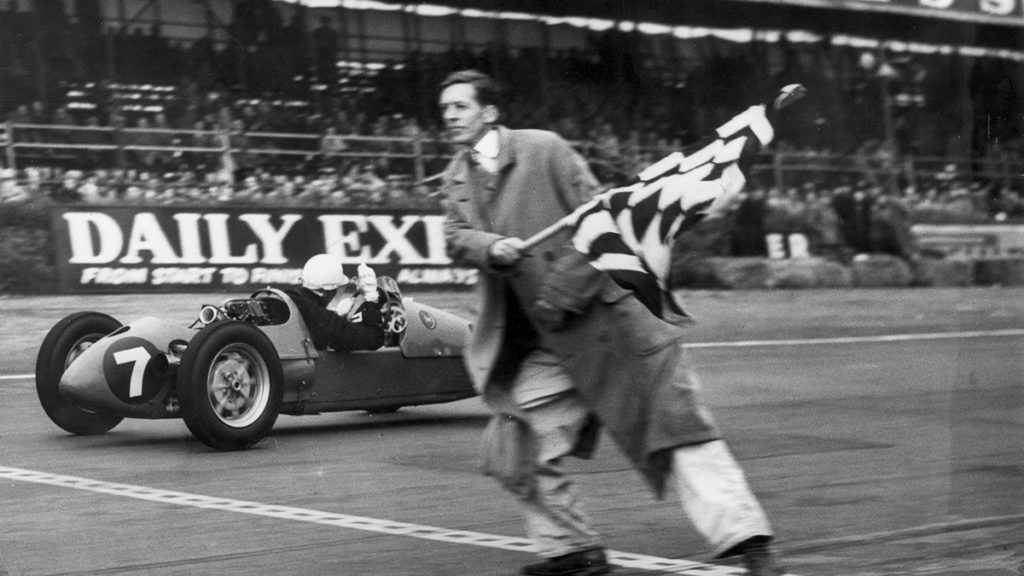

- Moss takes the chequered flag at the 1954 Daily Express International Trophy meeting, Silverstone, during yet another busy day (he also drove a Maserati 250F in the main race). He had intended to wind down his F3 commitments at the end of 1953, to focus on major single-seater and sports car races, but then accepted an offer to race Francis Beart’s Cooper when time allowed

- Moss with his Cooper MkIV at Brands Hatch on August 7, 1950, when a report in The Motor claimed 500cc F3 produced “the most exciting racing in England”. Moss won his heat and finished second to George Wicken in the first F3 race, despite gearbox trouble. Wicken later won the day’s main event, the £100 Daily Telegraph Trophy

- Moss’ headline achievements might be well known – not least his F1 conquests and his celebrated victories on both the Mille Miglia and the Targa Florio – but there are also a few curios on his CV, not least the fact he scored the first major international victory for a Borgward engine… That was in the 1959 Syracuse GP, an F2 race on April 25, at the wheel of Rob Walker’s Cooper T43. He drove the car on several other occasions that year, winning at Reims on July 5 – the same day that he raced a BRM P25 in the French GP – and finishing third to Jack Brabham and Graham Hill here at Brands Hatch, in the Kentish 100 on August 29

- Moss with rival Mike Hawthorn and BRM co-founder Raymond Mays in the Goodwood paddock, during the 1956 Glover Trophy meeting. Hawthorn raced a BRM P25 that weekend, as team-mate to Tony Brooks, and qualified third behind Moss (Maserati 250F) and Archie Scott Brown (Connaught). He retired from the race after losing a wheel. Moss went on to win, beating fellow 250F driver Roy Salvadori, and also took the spoils in the supporting sports car race, at the helm of Gilby Engineering’s Aston Martin DB3S

- A study of Moss from the 1958 Race of Two Worlds at Monza. The Indianapolis 500 is one of few major races missing from his repertoire, but this event taught him that there was a touch more to oval racing than simply turning left. Aware that his American rivals didn’t race in the rain, he went out in wet practice to prove a point… and very nearly crashed. He ran strongly in the first two heats, but the high banking loads took their toll upon his Maserati’s steering in the third and he skated into the barriers – at an estimated 150mph – while running fourth

- As a result of British constructors’ dissatisfaction with the 1.5-litre F1 rules imposed for 1961, the InterContinental Formula was set up as a potential alternative… but there were only five races – all in the UK – before the whole thing was canned. This is Moss at Silverstone in May, when he guided Rob Walker’s Cooper T53P-Climax to victory

- Moss walks away from his crashed BRM Type 25 at the 1959 Silverstone International Trophy. He had qualified the car on pole, eight tenths faster than Tony Brooks’ Ferrari 246, and was leading the race until brake failure during the early stages caused him to fly off the road. At this point in its history, BRM had still to win a major race… Moss being Moss, he kept himself busy during the day; he finished second in the international sports car race, at the wheel of a works Aston Martin DBR1, and won the GT event aboard a DB4 GT

- Monaco wasn’t the only venue at which Moss raced Rob Walker’s Lotus 18 without side panels. This is from the 1961 International 100 at Warwick Farm, New South Wales – a Formule Libre event that counted towards the Australian Gold Star Championship. Temperatures were said to have reached 106.9 degrees during the day. Moss finished well clear of Innes Ireland’s works Lotus 18. One year later, driving Walker’s Cooper T53P, he would win again at the same venue – the final victory of his mainstream racing career

- Moss on his way to another victory in Silverstone’s second – and final! – InterContinental Formula race, in the British Empire Trophy meeting on July 8, 1961. Either side of the two Silverstone events, the ill-fated series had visited Snetterton and Goodwood before fizzling out at Brands Hatch. Typically, this was not Moss’ sole success on the day; he also defeated a high-class GT field at the wheel of Walker’s Ferrari 250 GT SWB

- Moss drove almost everything… and Rob Walker seemed to enter almost everything. This is from the 1960 BARC 200, a Formula 2 race run at Aintree on April 30. Moss recovered after making a poor start from pole and took Walker’s Porsche 718/2 to victory ahead of the similar factory cars of Graham Hill and Jo Bonnier, with John Surtees (Cooper) fourth. Motor Sport described it as “one of the most interesting and exciting races seen for a long time at Aintree or anywhere else

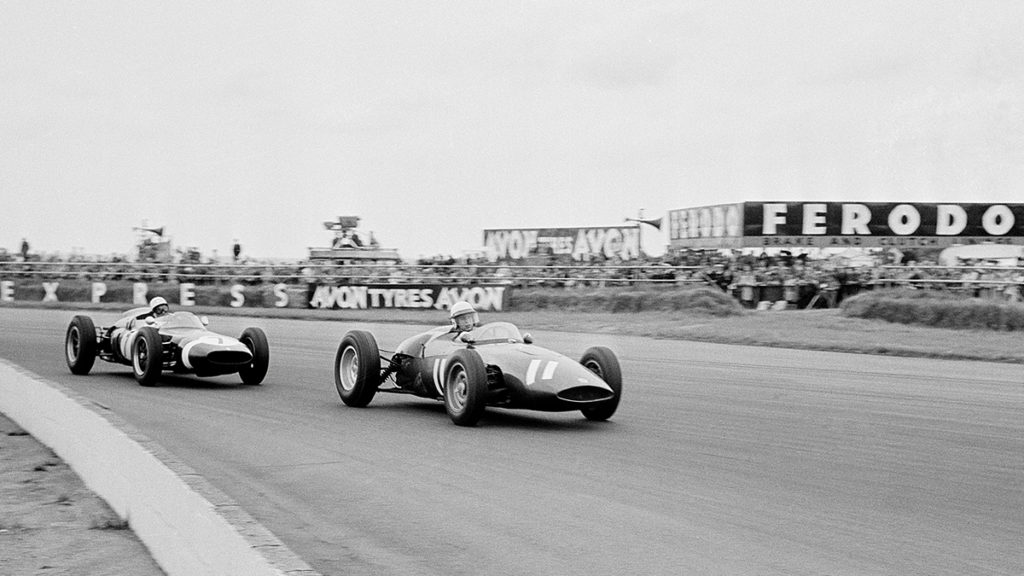

- More action from the 1961 British Empire Trophy meeting, with winner Moss chasing great rival Tony Brooks’ BRM P48. The meeting attracted a relatively low crowd, not helped by clashes with the Wimbledon tennis tournament and an England vs Australia Test Match, although it was perhaps also symbolic of the public’s general apathy when it came to InterContinental Formula racing. Brooks dropped out after 22 of the 52 laps, his engine having dropped a valve spring

- Moss in the pits during the 1961 Oulton Park Gold Cup meeting, when he took the Ferguson P99 to victory ahead of the Coopers of Jack Brabham and Bruce McLaren. He created another little slice of history by becoming the first – and so far only – driver to win an F1 race in a 4WD car