Chapter 1: The maverick that lives on - Stirling Moss and the timeless magic of Formula One

Stirling Moss was never crowned world champion, but with a buccaneering swagger and otherworldly genius, he embodied the very essence of the sport, leaving a legacy that still resonates today

From the moment Stirling Moss alighted from his first test of a Mercedes-Benz in December 1954 – an immaculate mechanic snapping to with hot water, soap, flannel and a clean towel – his world was never the same again and, despite his repeated ‘failures’ to become its official champion, nor would F1 be. For although five-time champion Juan Fangio was a household name, human dynamo Moss would become a global presence. His openness and willingness would accelerate its growth and extend its reach, and his stubbornness and genius would ensure that Britain eventually benefited most.

The first of three Monaco GP victories. By 1956, Moss had already won his first grand prix, the British in 1955. But with Mercedes-Benz now withdrawn from motor sport, its point proven, Stirling returned to a Maserati 250F – but this time as a works driver. At Monaco, Fangio took pole in his Lancia-Ferrari, but his former ‘apprentice’ showed him the way in the race, leading every lap. Strangely off form, Fangio took over Peter Collins’ car to finish second

F1’s 1954 return after a two-year Formula 2 interregnum – during which Moss had at best marked time in homegrown, undercooked machinery – brought a change of tack: ‘Pa’ Moss got ‘The Boy’ a Maserati 250F. Moss had it painted British racing green – young habits die hard – and set about convincing any doubters. An impressed works team drew him increasingly under its wing and the car would be entirely red – bar green noseband – by September’s Italian Grand Prix; Moss was a dozen laps from victory when its oil tank split. Mercedes-Benz, always the intended target, was convinced and formed a superteam to match its ambition and budget. Fangio remained virtually unassailable at the highest level, but it was very clear as to who would be picking up the great man’s baton in Formula 1.

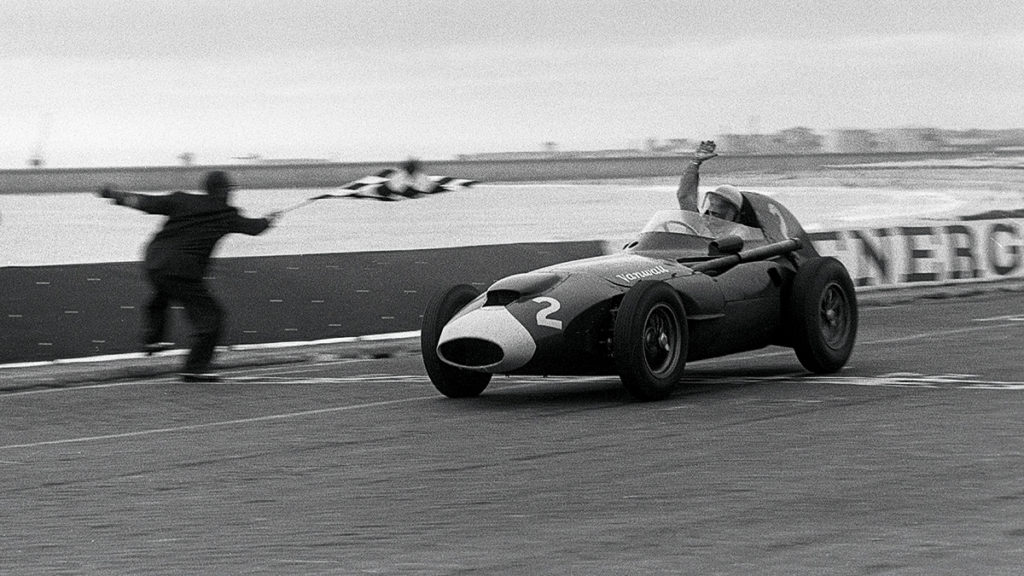

The Morocco Grand Prix, Casablanca, October 19, 1958. Moss presses on towards victory in the warm light of late afternoon. His Vanwall’s blunted nose is the scar of a collision with backmarker Wolfgang Seidel’s Maserati on lap 18, but it didn’t thwart his bid for victory. He needed the win and the fastest lap, with Ferrari’s Mike Hawthorn finishing no higher than third, to become champion. But Hawthorn was second, after Phil Hill obeyed team orders. Four times a winner in ’58 to Hawthorn’s single win, the title had slipped through his grasp once more

Moss duly did so, having become already the first Briton to win a world championship GP (in 1955) and – patriotic persistence rewarded – the first to score such a victory in a British car (1957), at Aintree in Mercedes-Benz and Vanwall respectively. The desolation he felt in 1958 at yet again being beaten to the world title – this time by a single point by counterpoint countryman Mike Hawthorn – would eventually give way to the realisation that he didn’t need to be crowned to be recognised as king by rivals and public alike. Moss decided to be kinder to himself from that point on and became a buccaneering privateer when every works team was scrambling to gain his signature.

Enlightenment would produce his best work, as the first to decode the dynamic benefits of placing engine behind driver, within a stiffer frame blessed with improved geometries and repeatable disc brakes rather than drums that grabbed before fading quickly. That signature laid-back driving style remained unaltered, but the insouciance it engendered masked an enquiring mind. Moss mastered swiftly the shallower/trail-braking corner entries now available, to carry more speed while using less road. Those who gave vain chase were left gasping and bamboozled.

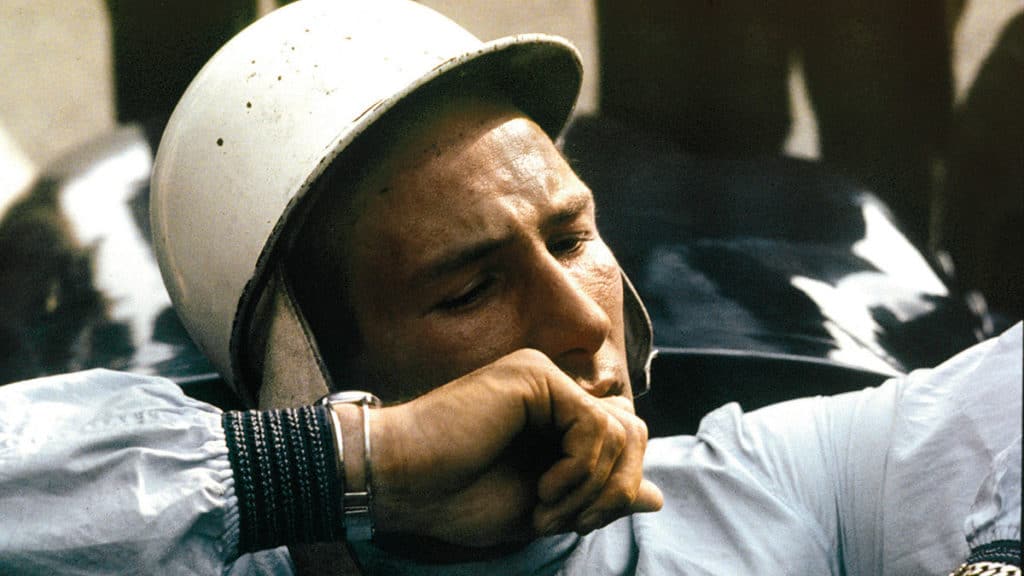

An evocative portrait by Swiss photographer Yves Debraine of Moss in his Vanwall on the grid before the start of the 1958 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. Promising young team-mate Stuart Lewis-Evans claimed pole position, but Stirling led from flag to flag, even lapping Hawthorn for good measure, on his way to a second GP win of the season

The peerless Moss in turn had eyes on the road, on the gauges flickering to the inherent unreliability of this more fragile machinery – British primacy was undeniable but not yet entirely robust – and also on the pretty girl in the crowd. It wasn’t just what he won but how he did so that was important, to him and his fans. Sensible chaps in worsted and brogues admired/envied him, fluttery mums in twinsets wanted to be with him, and schoolboys agog queued reverentially for his autograph. Moss had it all. Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had to circle the Earth to upstage him.

Yet Moss’ fame was about to rocket, too – as all else was seemingly snatched from him. His grievous accident in a non-championship Formula 1 race at Goodwood on the Easter Monday of 1962 left his life hanging by jangled neurons while an increasingly connected world strained to every bulletin. He emerged from hospital six months later with a limp, a sunken eye and a nagging doubt: could he bounce back from injury, as he had before?

Moss appears serene as he rounds Station Hairpin at Monaco on his way to that famous victory in 1961. Removing the side panels of his Rob Walker Lotus 18 had dual benefits: firstly it kept him cool, but it also removed a little weight

No. His exploratory test of a Lotus sports-racer at Goodwood brought a single insight: that spare capacity had been scrambled. He was 32, and had planned to race into his 40s. That would have involved his having to adapt to F1’s fundamental shifts of slicks-and-wings and sponsors – all of which surely would have been a cinch for the ‘old’ Moss. The ‘new’ Moss, however, could neither risk being merely very good nor afford the time to be so. To his surprise, he had emerged from hospital as a brand that needed protecting and capitalising.

The F1 that he had helped create would become richer and safer – he preferred the former – than he could have imagined, but it did so with the irreplaceable ‘Mr Motor Racing’ as a revered and vital link to its past glories. Moss was 90 when he died in April 2020 and had not raced a current F1 car for 58 years, yet indubitably his passing marked the end of an epoch. F1 is left facing its next and potentially last (if it’s not careful) fundamental shift as the world moves away from traditional engine power, without its touchstone.

- Moss on his way to victory in 1959 at Monsanto Park’s only world championship grand prix

- Glorious two-year ’50s burst represented a new era of success for the Silver Arrows before tragedy of Le Mans ’55 struck

- Moss in his green Vanwall VW10 returns to the pits after winning the 1958 Dutch Grand Prix in Zandvoort. The British driver was five points ahead of Ferrari’s Luigo Musso after the race. Musso died weeks later and Moss was destined to be pipped to the drivers’ championship by Ferrari’s Mike Hawthorn

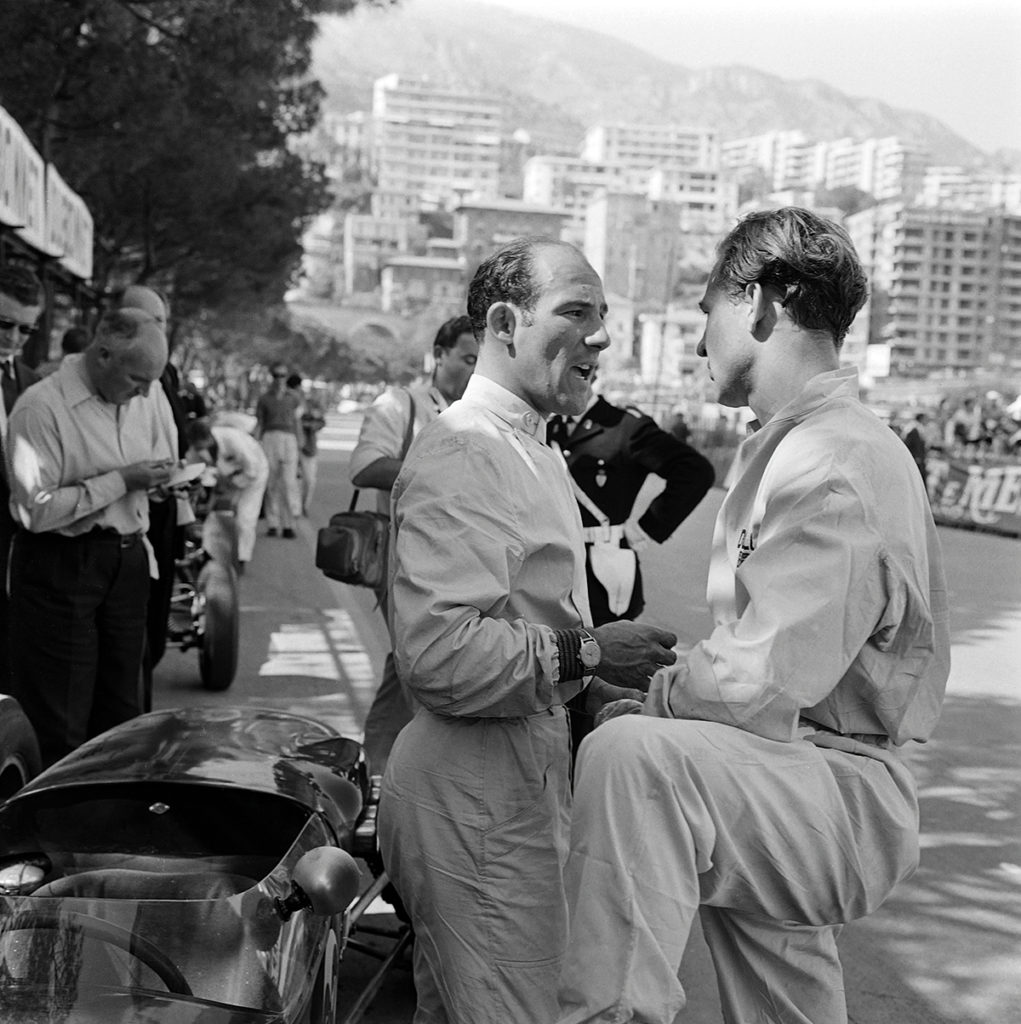

- Paddock talk at the Nürburgring before the German Grand Prix of 1961. As at Monaco earlier that year, Moss would defy the odds to beat the ‘Sharknose’ Ferraris. A canny choice of ‘green spot’ Dunlop tyres gave him the edge in changeable weather. It would be his last world championship grand prix win

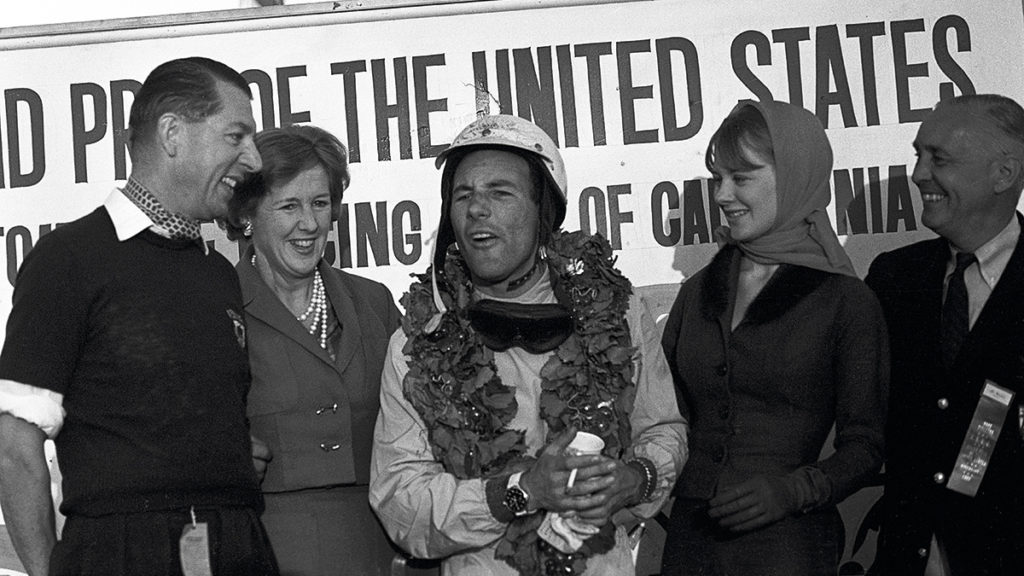

- mixing with royalty. Prince Rainier and Princess Grace congratulate Stirling on the second of his three Monaco Grand Prix wins, in 1960. Moss was comfortable in any social situation and as one of the world’s most famous sportsmen, everyone wanted to meet him

- A picture of nonchalance. The first of his two consecutive Monaco Grand Prix wins for Rob Walker in 1960 isn’t as celebrated as his second, but remains of great significance. It marked the first world championship grand prix victory for Lotus, as Moss overcame a pitstop to reconnect a loose plug lead to win. Team Lotus wouldn’t win a grand prix until Innes Ireland claimed the US GP in 1961

- Following his victory at Portugal’s Monsanto track in 1959, Moss won again at Monza to put himself right into title contention with Jack Brabham. The result in Rob Walker’s T51 confirmed Cooper as Britain’s second consecutive constructors’ world champion

- A year later, in November 1960, Moss would win the US Grand Prix at Riverside, California – the last of the 2.5-litre F1 era. The world title was long gone to Brabham once more, but the win was still significant for Stirling, who had returned to action following the serious injuries he had sustained at Spa in June. Here he enjoys a cigarette as patron and friend Rob Walker joins him to relish the moment

- In 1955, Moss joined Fangio at Mercedes, in what would be the team’s final grand prix season until 2010. Moss is captured rounding the Gasworks Hairpin with his Mercedes W196 at the Monaco Grand Prix in May 1955. It was not a good day for the constructor. For half the distance, Fangio and Moss were running 1-2, but Moss blew an engine, while Fangio and other Mercedes driver André Simon both retired

- The breakthrough: Moss scored his first world championship points in the Maserati 250F his father purchased to give ‘The Boy’ a proper shot at grand prix racing. At Spa for the Belgian GP he’d finish third in June 1954 behind Juan Manuel Fangio’s works Maserati and Maurice Trintignant’s Ferrari. He was a lap down, but still it was another milestone. Here he takes the La Source hairpin ready to begin another lap. Note the T-shirt in place of race overalls

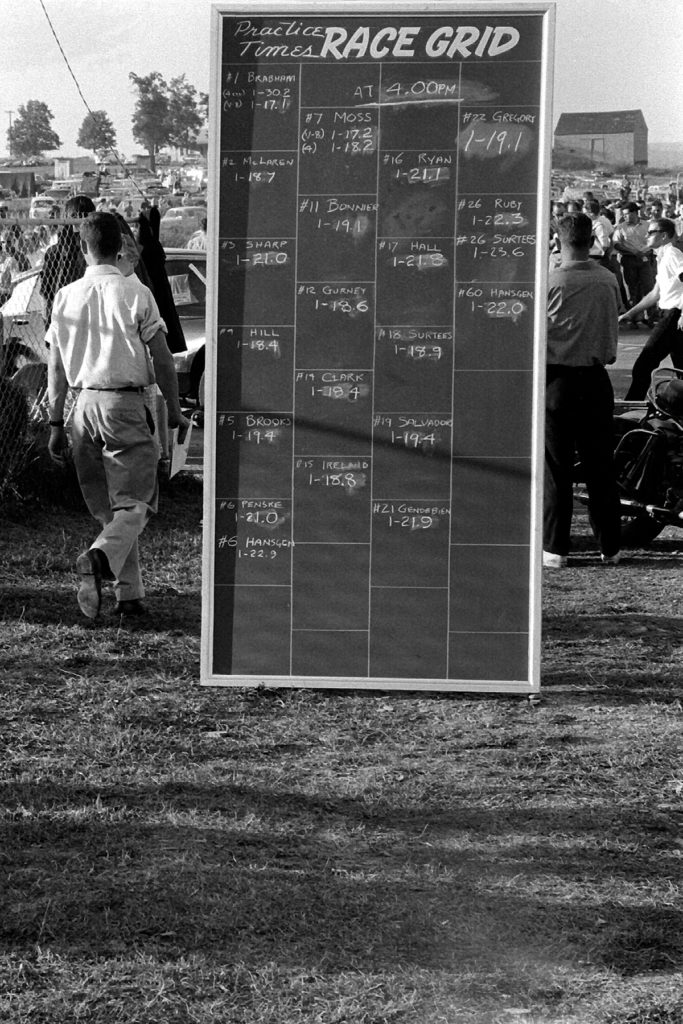

- No purple sector times here. A blackboard was used to display practice times for the 1961 United States GP at Watkins Glen. As it shows, Jack Brabham was a smidge quicker than Moss as they sampled the new Coventry Climax V8. Stirling ran the four-cylinder in the race and traded the lead with ‘Black Jack’ until both engines failed, leaving the way clear for Innes Ireland to give Team Lotus its first win. Near the bottom of the blackboard, note the name of a young American hopeful making his F1 debut. Roger Penske would finish eighth in a Cooper T53

- Moss in 1960

- Fangio in the ‘Piccolo’ Maserati 250F and Moss in his Vanwall go wheel to wheel at Reims in July 1958. Stirling would finish second to Ferrari’s Mike Hawthorn – the only win of his world champion season – while the Maestro finished fourth in what turned out to be his final GP. The day was overshadowed by the death of Luigi Musso, who was thrown from his Ferrari when he lost control at the right-hander after the pits

- Harry Schell (4) is eager to get going, but Moss would star on his first start in the new Vanwall at the 1956 BRDC International Trophy at Silverstone. Alongside is a typically composed Fangio and Mike Hawthorn in a BRM Type 25. Moss and Hawthorn would enjoy a spirited dice and share a new lap record, but ultimately Stirling would prove the new force in British motor sport

- the press don’t wait for Moss to step out of the Lotus 18 cockpit at Monaco in 1961. He has just driven 100 laps of the street track in 2hr 45min 50.1sec to win after one of the greatest drives of his life – so no wonder he’s smiling. Stirling didn’t train because he didn’t need to; he was always driving. He was fitter and stronger than most of his rivals, which was just another reason why he usually beat them

- Porto in 1958, a crucial turning point in the outcome of the world championship. Rival Hawthorn, running second, spun on the last lap, rejoined by driving against the direction of travel and was disqualified. Stirling intervened, arguing that Mike had driven on a pavement, not the circuit itself – and Hawthorn had his points back. At season’s end they would be separated by just one point. If only Moss hadn’t misread his pit signals in Portugal and pushed for the fastest lap to gain the extra point it would have given him…

- The Maestro congratulates Stirling after his 1955 Aintree win. Had Fangio backed off to allow his young friend a special home win? Even when Stirling asked him years later, the reply was enigmatic: “It was your day.” Ever the gentleman, Fangio would never admit to such a gift, even if he had bestowed it. The pair spent that one season as team-mates at Mercedes-Benz – and a lifetime as friends

- Moss guides his Mercedes-Benz through the flat Aintree fields to victory at the 1955 British Grand Prix. It was a superb outing for the manufacturer, finishing 1-2-3-4

- Moss and Innes Ireland compare notes at Monaco in 1960. Ireland had recently beaten Moss twice in one day at Goodwood, in the Glover Trophy and Lavant Cup, in F1 and F2 versions of Colin Chapman’s Lotus 18. The next month he did it again at Silverstone’s International Trophy. It had convinced Stirling that he needed Rob Walker to make the switch from Coopers. Victory in Monte Carlo would fully justify the move

- Looking out at Monza from the pits in 1954. At 25, was Moss too young to be brought into the fold at Mercedes-Benz? That was the doubt. But he’d already taken an impressive pole position in the wet at Bern and now here at Monza would come conclusive proof of what he was made of. Lining up in his Maserati 250F beside Fangio’s streamliner W196 and Alberto Ascari’s Ferrari, Stirling drove with such illustrious company as an equal, then sensationally took the lead – only for a split oil pipe to end the fairy tale. Fangio won, but the point had been made. Moss would be a Mercedes driver for 1955.

- Tony Vandervell in straw hat leans in to hear Stirling’s thoughts on the Vanwall at the Nürburgring in 1958. Compare the size of the VW5 to the rear-engined Cooper T43 in which Moss won the Argentine Grand Prix at the start of the season. Formula 1 is changing and soon such big beasts will be dinosaurs. At the ’Ring, Stirling represented one quarter of an all-British battle for victory (another sign of changing times) and would initially lead Ferrari duo Hawthorn and Collins, plus team-mate Brooks – until magneto failure forced him to park on lap four. Brooks now stepped up to overhaul the Ferraris, before tragedy struck: Collins, determined to fight back, crashed to his death at Pflanzgarten, witnessed by his ‘Mon Ami Mate’. A broken clutch would account for a devastated Hawthorn, as Brooks scored a sombre win. This also was motor racing in 1958

- Disaster struck at Goodwood in 1962 when Moss, then age 32, crashed in the F1 Glover Trophy race in wet conditions driving a Lotus V8 in UDT-Laystall colours. Moss was beside Graham Hill attempting to unlap himself when he lost control and hit a bank head on. He was trapped in the car for 45 minutes and suffered skull and brain injuries. He was in a coma for a month but remembers little about the accident itself. It was his final F1 drive