Chapter 4: Stirling Moss' versatility shines in rallying and speed record breaks

From Alpine rallies to salt-flat speed records, Moss turned his hand to a dizzying array of side projects and in doing so became motor racing’s greatest all-rounder

Before Moss was understandably drawn in the second half of his career to the winter sun of the Southern Hemisphere – racing in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – ‘anything, anywhere’ meant tackling European rallies, plugging Derbyshire mud or pounding a French speed bowl in search of another mind-bending record, such as, say, averaging more than 100mph for a week: a true test of Moss’ ‘movement is tranquillity’ mantra.

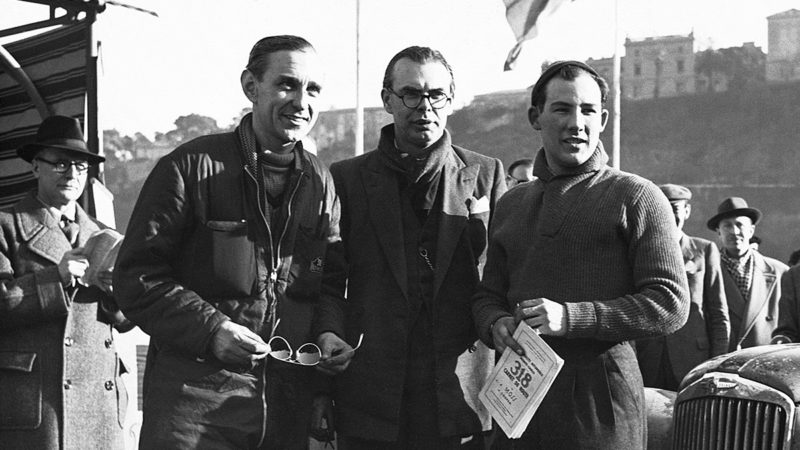

Check out his 1952 itinerary. For a flat fee of £50 from the Rootes Group, he finished second in January’s snowbound Monte Carlo Rally, missing out on victory by four seconds at the wheel of a three-up Sunbeam-Talbot 90 saloon; he was co-driven by BRDC secretary Desmond Scannell and John A Cooper of Autocar. On his return, Moss contested a trial in a Ford-engined special supplied by ex-racer Cuth Harrison. Then he contested the Lyon-Charbonnières Rally in his own Jaguar XK120 coupé, co-driven by Autosport editor Gregor Grant and finishing second in class. In July, he won his class in the Alpine with a penalty-free run in a Sunbeam navigated by John Cutts. He rounded off this manifold campaign with the aforementioned week-long blat around Montlhéry – in an XK120 coupé shared with Leslie Johnson, Jack Fairman and Bert Hadley – and by driving a Humber Super Snipe through 15 European countries in just four days by way of a publicity stunt. On the latter occasion he was joined again by Johnson, a glutton for punishment clearly, Cutts and mechanic David Humphrey.

The more clement Montes of 1953 and 1954 provided neither the same thrill nor result of his first – Moss finished sixth and 15th in Sunbeams – but the 1954 Alpine Rally more than made up for it, with snow in summer. Moss was endeavouring to become only the second recipient of a Coupe des Alpes en Or, awarded for three consecutive unpenalised runs. He drove so hard at one point that he burst into tears at the conclusion of his exertion. Once again he had left nothing on the table. And that perhaps explains what happened at the finish.

Word had got out that the transmission of his Sunbeam-Talbot Alpine convertible – keeping the crew warm had been a genuine problem – was not functioning as it ought, for which penalties would be accrued. With a scrutineer alongside, Moss did something that he had never done before nor would again: cheated. By making a great show of waggling the columm-mounted change while surreptitiously flicking the overdrive switch he was able to conceal the fact that bottom and top gears had gone AWOL. Félicitations, Monsieur Moss! He reckoned that he had bloody well earned it, too.

Autocar’s John Cooper, BRDC secretary Desmond Scannell and Moss pose with their Sunbeam Talbot 90 during the 1953 Monte Carlo Rally, in which they finished sixth. The event was won by speed camera pioneer Maurice Gatsonides in a Ford Zephyr

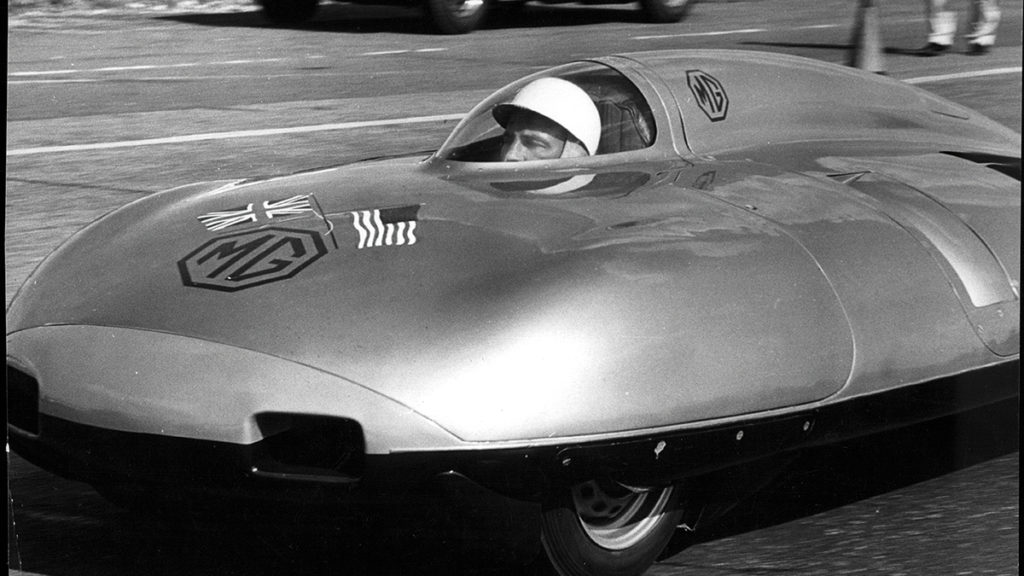

Increasing racing opportunities began to impinge on such ‘sidelines’ thereafter – and the lucrative Tours de France Auto of September 1956 and 1957 contained more of a circuit element to them in any case; Moss finishing second and fourth, his Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing outpaced by the latest GT Ferraris. He did, however, agree to gun a (more) streamlined Lotus XI around Monza’s jarring bankings – it broke, unsurprisingly – and to guide MG’s ‘Roaring Raindrop’ EX181 at Bonneville in Utah. Although he was successful in setting several capacity class world records on the famously disorientating salt flats – including 245.64mph for the flying kilo (despite losing third gear) – he did not enjoy the experience. Lying flat on his back in this flying saucer-on-wheels while mechanics fastened down its bubble canopy was too emblematic for his liking. Yet two years later he found himself back at Bonneville with the same car – and slightly at a loss as to why exactly. He was not sorry to have to leave the task to Phil Hill after bad weather ruled out his attempt. His true calling was calling – he had to return to contest the Oulton Park Gold Cup (which he won in a Cooper) – and in truth there was no longer any need for him to leave his comfort zone so far behind in order to access all the competition and diversity that he could wish for or handle.

Moss, more than any other driver, had created this new motor sport world. He was at the peak of his powers and able to call the shots, though perversely often he placed himself at a disadvantage. This top dog was happier being the underdog. That ‘luxury’ might have changed given that he had divined the threat posed by Jim Clark in the works Lotus – but we will never know how his deal with Ferrari might have played out. There is more than plenty here, however, to be sure that Moss was – and remains – the greatest all-rounder.

- Moss on the 1954 Monte. Commenting on a fairly low-key showing for British cars, Motor Sport wrote that the winning Lancia Aurelia was “very potent and some protests were entered on the grounds that an insufficient quantity had been built to comply with the regulations”

- More commonly seen in his trademark Herbert Johnson helmet, Moss opted for the alternative of a bobble hat on the Monte. As his career progressed he was able to obtain his competitive fix in warmer winter climes, notably the Bahamas and the Antipodes

- In June, Moss would commence his world championship grand prix campaign in a Maserati 250F at Spa, but the pace was slightly gentler in the early part of 1954. On the Monte Carlo Rally he shared a Sunbeam Talbot 90 with Desmond Scannell, finishing 15th overall

- Notionally this Jaguar XK120 was Moss’ daily transport, loaned to him as part of his deal for driving for the firm in the early ’50s. He also competed with it, however, and finished a class-winning 13th in the 1952 Daily Express International Rally

- Moss at speed at Bonneville in 1957. He managed 245.64mph in MG’s EX181, comfortably quicker than the 203mph Class F record Goldie Gardner had set in the late 1930s

- 29th May 1957: British racing driver Stirling Moss in his custom built car at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, where he attempted to break the International Class F speed record. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

- Moss climbs on board during his successful Bonneville crusade in 1957. Despite his reservations about the wisdom of such projects, he returned to the salt flats two years later but was unable to run due to adverse weather conditions. American star Phil Hill took his place

- Moss strikes a contemplative pose. Beneath its teardrop exterior, EX181 featured a supercharged MGA twin-cam engine. Running on a cocktail of methanol, nitrobenzene, acetone and sulphuric ether, it produced 290bhp at 7000rpm

- Moss in the world’s fastest MG: EX181 was later fitted with a bigger engine and Phil Hill managed a 254.91mph run at Bonneville