It was in the following year that he first came to the attention of the motor racing press, driving a Hispano-Suiza in the Monte Carlo rally, and finishing third in his Bugatti T35 behind the Talbots of Sir Henry Segrave and Jules Moriceau in the GP de Provence at Miramas. The British motoring press took little account of him, considering him French rather than British in spite of his name and being in any case far more concerned with machinery than men. Yet in 1927 he made his one and apparently only appearance in England when he was nominated as the reserve driver for Count Caberto Conelli‘s Bugatti in the RAC Grand Prix at Brooklands. Conelli ran out of fuel and pushed the car back to the pits, whereupon Williams took over the driving, had a mighty moment when trying to pass Malcolm Campbell, and thereafter continued at a more sober pace. The car failed to finish the race ‘flagged off’ as they said in those days though some reports of the race classify it as sixth. The winner was Robert Benoist, who would become a close friend of Willy and with whom his later life would be inextricably entwined.

In 1928 he became a more regular competitor and a more successful one. His biggest win of the year was in the French GP at St Gaudens, but that year the race was a shadow of its former self, being held for sports cars on a handicap basis. Williams’ Bugatti T35 was apparently the only works entry in the field. More impressive and proof that this Anglo-Frenchman could drive a bit was his performance in the Italian GP at Monza, where he raced wheel-to-wheel with Achille Varzi‘s Alfa P2 and the Bugattis of Tazio Nuvolari and Louis Chiron until his engine blew.

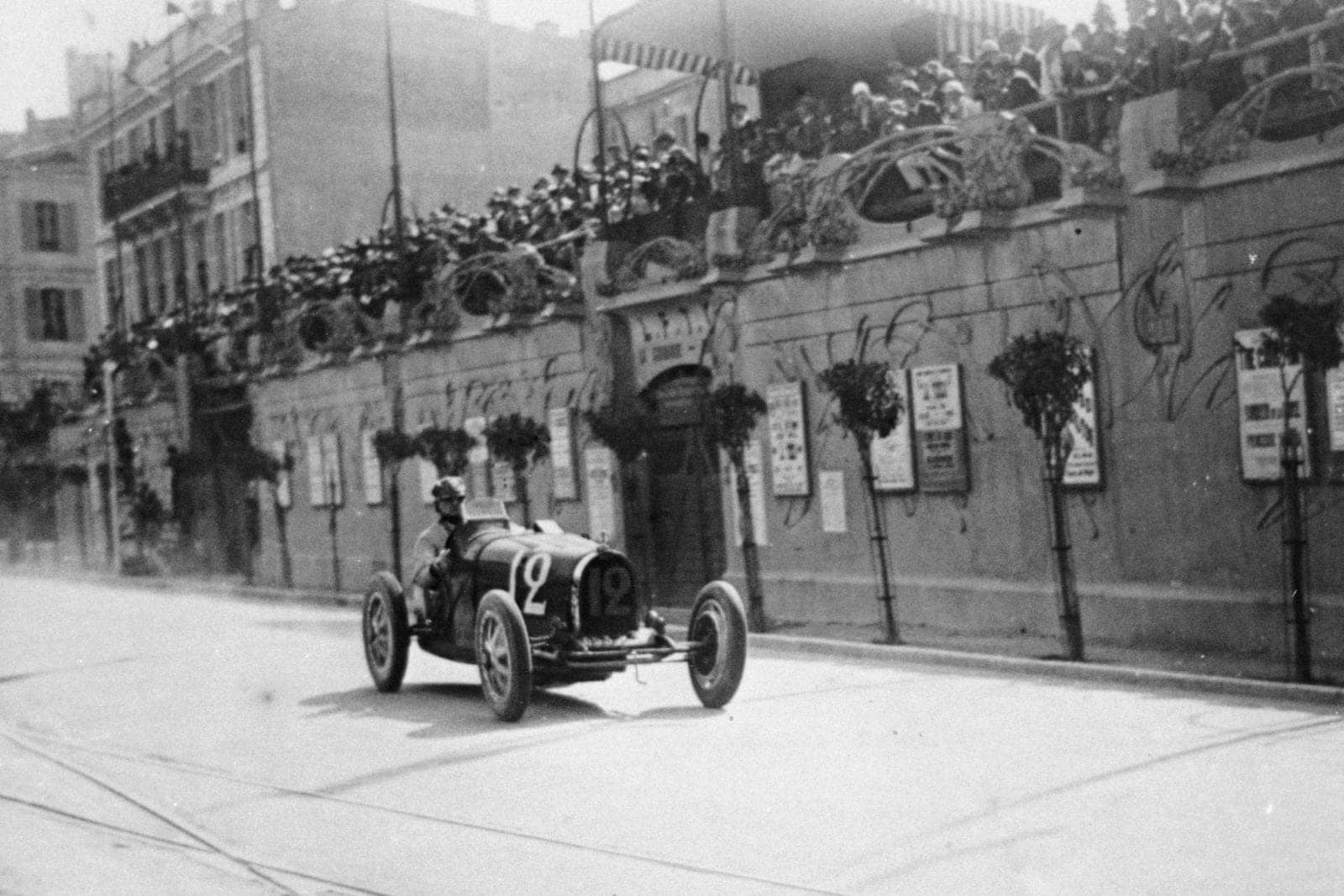

By 1929 he was a regular competitor on the Continental scene and scored the biggest victory of his career by winning the inaugural Monaco GP. Although the conflicting Mille Miglia removed some of the strongest potential opponents, it was by no means an easy race, Williams fighting tooth and nail with the 7.1-litre Mercedes SSK of Rudi Caracciola before taking the flag. His Bugatti was painted green, yet another indication of his British ancestry, but the contemporary accounts in Motor Sport and Autocar pay no more than lip service to his nationality. He also won the French GP, for the second year running, this time held at Le Mans and again attracting less than a top-class field, and he competed in the Ulster TT, his second and final racing appearance in the British Isles.

There were no results in 1930 to match those of the previous year, though he drove splendidly in the French GP at Pau, leading and setting fastest lap before the car broke down, handing victory to Philippe Etancelin‘s Bugatti from Tim Birkin‘s Bentley. The most significant win of his career came in 1931, when he shared a Bugatti T51 with Conelli to victory in the Belgian GP at Spa-Francorchamps. The Grand Prix formula for that year called for races of 10 hours in duration and for most of those 10 hours Williams and Conelli were locked in battle with the Alfa Romeo 8C Monza of Nuvolari and Baconin Borzacchini, which ultimately finished on the same lap. It was the first Grande Epreuve victory for a Briton since Henry Segrave had won the 1924 French GP for Sunbeam, but you would never have known it from reading the contemporary reports in the British specialist press, which preferred to dwell on Birkin and Brian Lewis‘s drive to fourth place in an Alfa.

From there on the racing career of Williams started to fizzle out. He won at La Baule the Brittany seaside resort that was by then his home town in 1931, 1932 and 1933; he finished seventh at Monaco in 1932 and 1933, sixth in the French GP in 1931 and the Belgian GP in 1932. But by 1933 the Bugattis were less competitive in Grand Prix racing, and at the end of the season Williams retired, apparently to breed Aberdeen tethers. There was a brief comeback in 1936, when he drove a Bugatti T59 to ninth place at Monaco, and he also finished sixth in the French GP, sharing a T57G with Pierre Veyron. But the short racing career of this tall, ramrod-straight Anglo-Frenchman was now over.