Subsequently he was quickest in pre-season testing at Estoril. But producing in testing was one thing, to perform in the cauldron of a GP weekend especially back in the country where he was for so long confined to hospital presented the ultimate test.

He confesses the tension got to him.

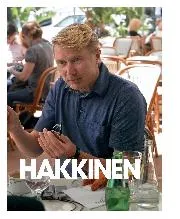

“Sitting in the aeroplane before I landed in Melbourne I was looking out the window, seeing Australia, and my mind was thinking, ‘This is the country where you had a big shunt. Then you just tell yourself, ‘Don’t think about it. Close the curtains and just don’t look out’. If you do start thinking about it your emotions can have too much effect on you and you never know what’s going to happen. It’s very tricky. Very difficult. One good thing was that going around the track on the driver parade I realised how many fans I have in Australia. That gave me a lot of courage, a lot of strength to continue.”

Left stunned by his driver’s pace in testing, an upbeat McLaren boss Ron Dennis claimed, “The accident has matured Mika a bit. He is more professional than before.”

Asked whether he had changed, the Finn responded: “Yeah, my hair is a bit shorter!” but the humour was forced, and for much the Melbourne weekend the usual ready smile was nowhere to be seen.

“Probably I have changed,” he admits in a moment of reflection, “but it’s always hard to see the changes in yourself. You just think to yourself, ‘I’m always the same guy, the same person’, until somebody comes and says, ‘What’s going on with you?’

“When you have something like that [the accident] it naturally changes your life a bit; changes your thinking on anything. Maybe when I am out on a racetrack I am not taking so many risks I am more calculating – I used to take them every lap; now it’s maybe every second lap.”

Sceptics were quick to pounce on the fact that he was clearly ill at ease with the media. At a brief conference he virtually retreated inside his shell, showing evident distress as the battery of flash guns were fired off in his direction. “It’s very uncomfortable to try and start talking about some important things in your life to somebody else if there are 15 cameras flashing in front of you,” he explained afterwards.

Rosberg betrays little surprise when the news of Mika’s reaction is relayed to him. ”He was scared,” he says candidly. “Scared to face people and hear them saying, ‘Is he still able to do it?’ He’s been to hell and back. He’s just spent two months alone with his girlfriend with nothing to do all day but read the horror stories in the papers. Of course he was uncomfortable. Put yourself on a platform with the whole world staring at you for a weakness, wondering if you could still see like you used to or not. How would you feel?

“Just to be here and finish this race was my personal victory.”

“He is still very nervous of people, worried about the world saying he is no longer able to race. You know that it only takes a bad run now and people are immediately saying, ‘Hey, hey, poor Mika. He hasn’t got it any more…

Has he still got what it takes? On the evidence of Melbourne you would have to say ‘yes’. As is customary, Hakkinen languished well down the timesheets for most of qualifying, only to produce that one-off late lap that infuriates team-mates and technicians alike. Having out-qualified David Coulthard who, not so many months ago, was spoiling Damon Hill’s title challenge he outraced him too. In the circumstances, with a car that isn’t yet a front-runner, you could have asked no more but to start fifth and finish in the same position. If McLaren had problems in Australia, the finger couldn’t be pointed in his direction.

“I think he did a good job to keep those guys behind him in the race,” sums up Rosberg. “Coulthard was struggling to get past a Footwork, Mika was losing two and a half seconds a lap to the leaders. One slip and he would have been ninth. I’m happy and proud of his determination. He did a good job.”

After the race the Finn admitted he had mixed feelings. “It’s difficult,” he mused, “because some people are saying this comeback is a sensation. It’s not. I don’t call fifth place a sensation. But in another sense just to be here and finish this race was my personal victory.”

When he spoke to Rosberg that night, he was more annoyed than he was elated, and his comments to the press before he left the track betrayed his disappointment. “The car’s not quick enough,” he said bluntly. “At the end of the race I was really tired, which I think is natural anyway, but I also think I did more work than anybody else out there! The car wasn’t exactly like it should have been. Now it’s up to the engineers and designers to give David and myself a car that is capable of competing.

“I’m not after finishing fifth or third, or something like that. I’m not interested and I don’t want it. That’s not I want from my career. I want to win and there’s nothing else that counts.”