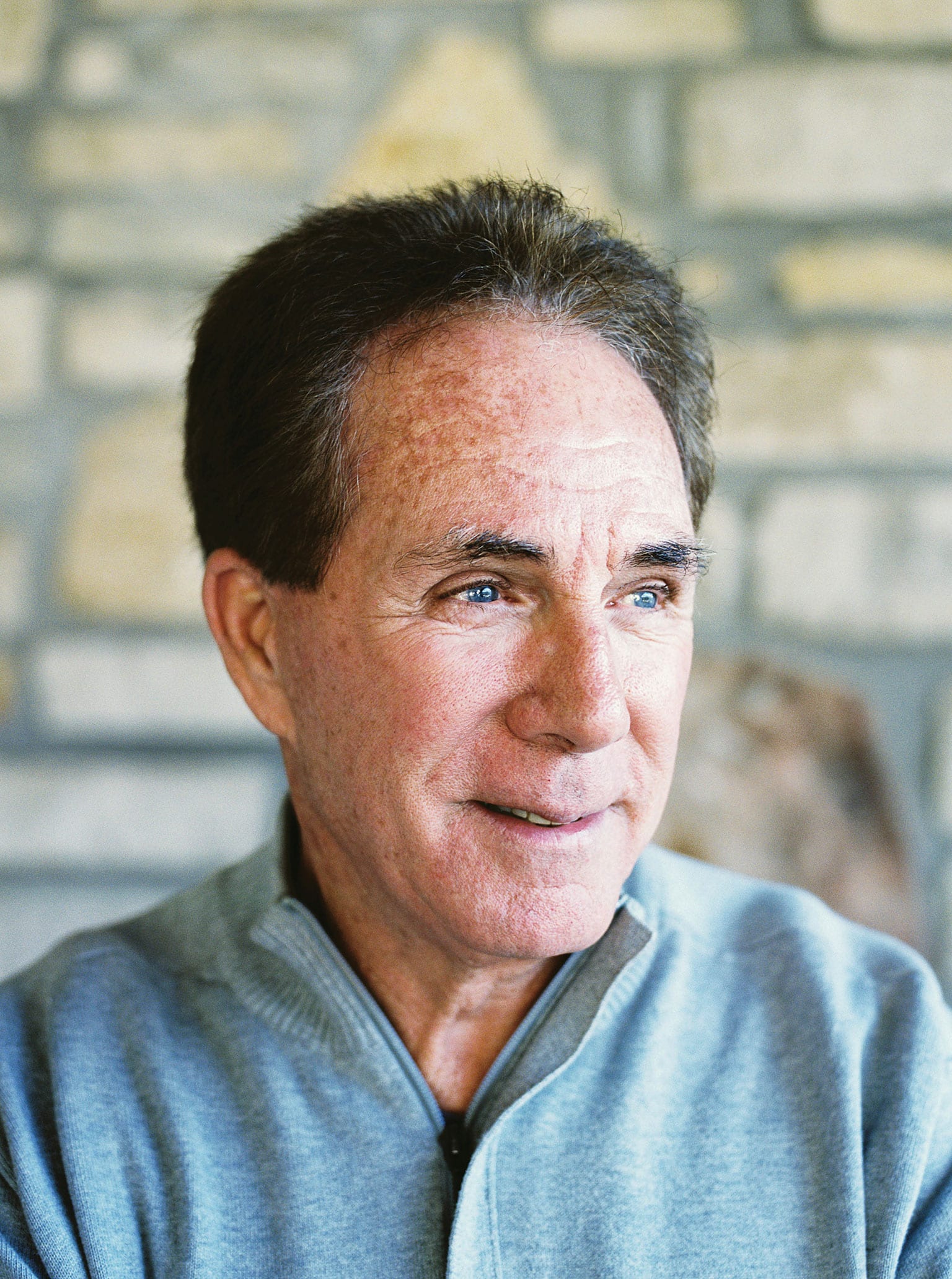

Lunch with... Darrell Waltrip

At his career peak he created many NASCAR headlines. Nowadays he’s at the track to analyse major talking points on TV

Abigail Bobo

“When I first started out in NASCAR in the 1960s,” says Darrell Waltrip, “it was pretty much just the good ol’ boys. Rough and ready on the track, rough and ready off it. It was popular in the South, drawing spectators who were local to each track, but it hadn’t moved on much from the old days on dirt. By the time I stopped racing in 2000 it had become a highly promoted, highly sophisticated show, popular from coast to coast, with packed stands and huge TV audiences.

“During the 29 seasons I raced in front-line NASCAR I did more than 800 Sprint Cup races. I was champion three years, runner-up three years. But I reckon more people know me now as the guy doing the race analysis on Fox TV than ever knew me when I was racing.”

Nevertheless, on the NASCAR circuit Darrell was always one of the highest-profile drivers. Early in his career he was known as ‘Jaws’, after the then-popular movie about a man-eating shark, because he was a talker, and always had something controversial to say about the racing and about his fellow-racers. “Right from the beginning I didn’t want to see newspaper headlines just saying ‘Petty wins’ or ‘Pearson wins’. I wanted to see ‘Petty wins, but Waltrip says…’ ”

His extrovert image, first as the man the crowds loved to hate and later as the man the crowds loved, was meat and drink to race promoters and was part of a media-savvy strategy that was new to NASCAR. It lives on today in his outspoken TV persona, from his catchphrase at the start of each race – “Boogity, boogity, boogity, let’s go racing, boys and girls” – to expressions like “he’s using the chrome horn” to describe a driver deliberately bumping the back of the car in front. He is also the voice of Darrell Cartrip, the No 17 Chevrolet in the Cars series of animated kids’ movies.

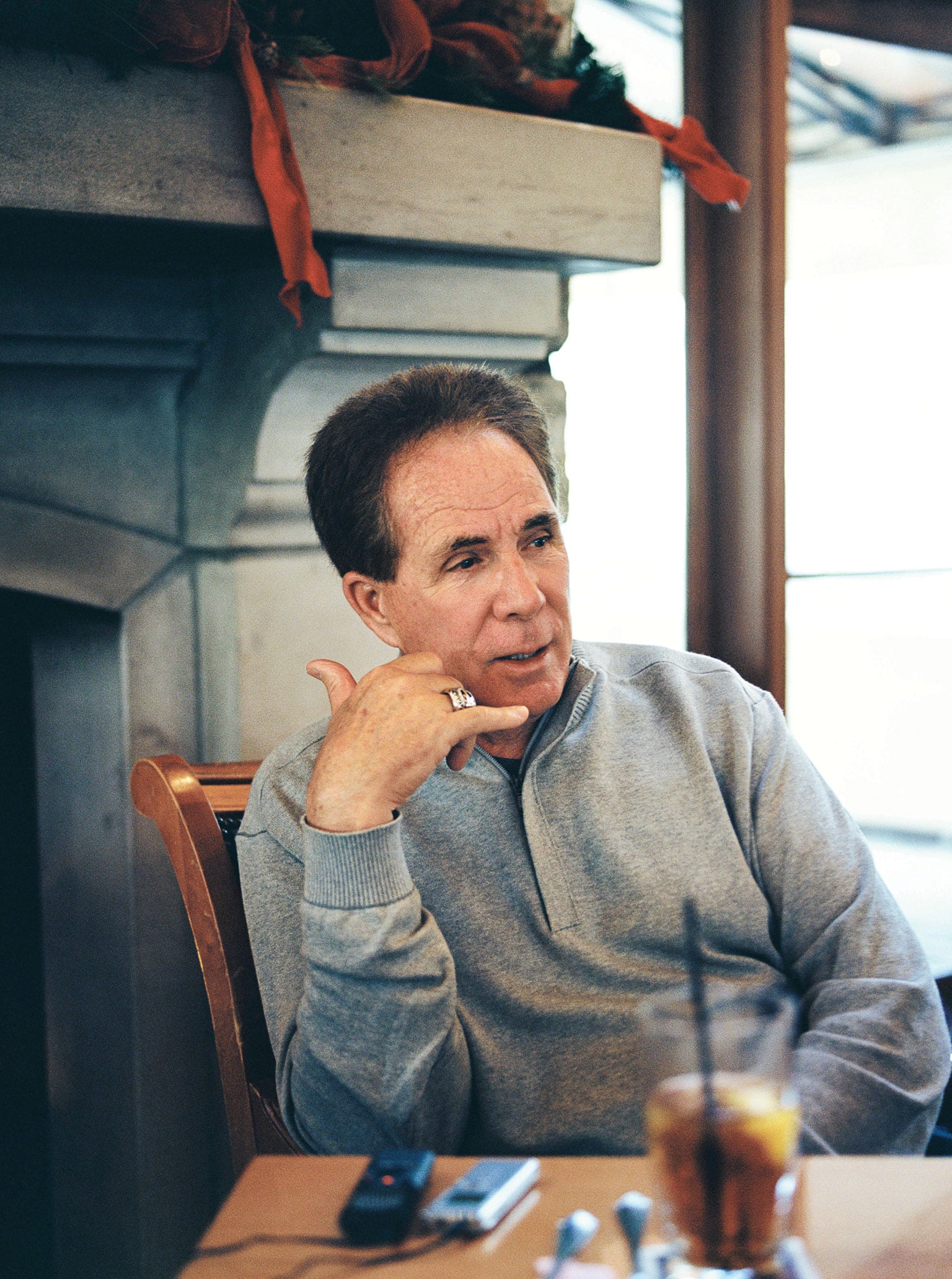

Darrell was born in 1947 in the Kentucky town of Owensboro, but since his early 20s home for him and wife Stevie has been Franklin, Tennessee. We meet for an excellent lunch in Franklin’s Vanderbilt Legends golf club, and Darrell turns out to be charming, good-humoured, self-deprecating and very far from his old Jaws image. In fact he prefers to be called DW – or, as everyone pronounces it down there, Dee-Dubya. He is Franklin’s local celebrity and they love him at the golf club. As he orders bean soup and chicken masala with mini mushrooms and mash, he jokes with the waitress: “This guy’s come all the way from London, England to buy me lunch, so you’d better show him some respect.”

***

“My dad drove a truck for Pepsi-Cola. My mom worked too, and we were five kids. Dad was a shade-tree mechanic: he’d get up Sunday morning and say, ‘I guess I’ll pull the engine and check the bearings.’ He’d park his car under a tree, sling a hoist from a big branch, yank out the engine, tear it down, have it all back together by sundown. That was my dad: he liked to tinker.

“My grandma, from when I was about six she’d take me to the races at the Nashville Fairgrounds. She was five foot tall, weighed 100 pounds, cigarette in one hand, cup of coffee in the other, scratching around like a little bandy rooster, cussing like a sailor. She was a fan of a local driver called G C Spencer, and she hated his main rival, Gene Coombs, known as The Brute. If the Brute beat GC she’d drag me down to the pits after the race and I’d have to stand there while she bawled out The Brute. So I learned a lesson very early: if you can’t get the crowd loving you, get the crowd hating you. Then the promoters will want you.

“My vacation job was helping Dad deliver Pepsis and Dr Peppers. One day we delivered to a hardware store that also sold karts, and we persuaded the guy to let me try one on the local airfield. I went like I was born with a kart under me, and we ended up buying a second-hand one for $300 – which was a lot of money to Dad. We started racing it, but it was old and heavy, and I got nowhere. So we managed to trade up to a newer, lighter Dart-McCulloch, and I was off. Over the next few years I won hundreds of kart races, culminating in a big WKA event in Missouri.

“At 16 I got me this old Chevy coupe, built it up into a dirt car and took it to the local dirt oval, Ellis Speedway. Wearing a football helmet and a pair of bubble goggles I set off, tried to drive it like my kart, got as far as Turn Three and went straight into the wall. Never made a lap. We mended it and came back, but I was never happy on dirt. Then we went to another track at Whitesville, which was paved, and from the get-go I started winning.

“A couple of the local cops had race cars that they took to Whitesville. When I kicked their butts they weren’t too pleased, and they started looking out for me on the roads around Owensboro. My mom’s dad was the deputy sheriff, which helped some, but I did have some brushes with the law in those days. The worst was when a friend let me try his Pontiac GTO, and after I found out how fast it would go our ride turned into a police chase. That ended up with bullet holes in the GTO.

“I was stupid enough to take the old ’58 Ford I’d been racing at Whitesville all the way down to Daytona, Florida. I was going to run a 300-mile race in that car. At first we couldn’t get it through scrutineering. It didn’t even have seat belts. It did have a 427 Holman & Moody tunnel-port motor, so it could haul ass, but the rest of the car was a piece of crap. We’d only been running on little tracks, and here I was at a superspeedway.

“Eventually I screwed myself up to take the proper high line around the banking. I wasn’t going very fast, probably about 160mph, but I was scared out of my wits. In the race I was going OK, but whenever somebody lapped me the engine revs would scream up. I reckoned the clutch was slipping. Same thing every time one of the fast guys went by. What was happening was the draft from the other car was getting under my car and lifting the back wheels off the ground. We’d never heard of aerodynamics then.

“At Whitesville I raced against a sweet guy called P B Crowell, and when PB crashed and hurt himself he offered me his car, which had been built up by one of the top NASCAR racers, Bobby Allison. I used to go down to Bobby’s place in Hueytown, Alabama to pick up parts and stuff, and he taught me a lot about setting up a car. So I started winning in that, and I won the track championship at the Nashville Fairgrounds in 1970.”

That led to a serious NASCAR mount, a ’67 Ford Fairlane Mario Andretti had used to win the Daytona 500 four years before. “I managed to talk $25,000 out of a transport company to put their name on the side. The car cost $12,500, with $12,500 to run it. That car was fast. Holman & Moody had got it all cheated up with narrowed bodywork to reduce the frontal area, which you had to do back then to keep up.” It was a shoestring operation, but now Darrell was running in NASCAR’s top division – then called the Winston Cup – against the likes of Richard Petty, David Pearson and Cale Yarborough.

***

“First round was the 1972 Daytona 500. There was the ARCA Daytona race two weeks before, and I decided to do that to get some feel for the car and the track. I qualified third, right up there with the hot dogs. End of lap one I’m running third, and the guy in front blows his engine, oil and crap all over the track. I spin, everybody misses me, then I hit the wall. Man, am I sick.

“So we have work to do to get ready for the 500. We can’t buy new standard fenders from the local Ford dealer, because of course they won’t fit the narrowed car. So we work day and night getting it more or less straight with a two-ton jack and hammers. Qualified pretty good, but the handling was all over the place, and in the race I got in traffic and hit the wall again. After that we took it home and fixed it properly, with a ’71 Mercury shell.”

In the Winston Cup events Darrell began to notch up top-five and then top-three finishes, but it wasn’t until 1975 that he scored his first big win, at his home track of Nashville. “I was running as an owner/driver. I prepared the car and had six or seven good guys working with me under Jake Elder, who was my crew chief. I had no money, I was just living from week to week. I’d pay them on Friday and then, if the weekend didn’t go well, I’d ask to borrow it back on Monday. But all of them were racers, so we just got on with it.

“Plus for a lot of this time I was still running the fairgrounds circuit four nights a week in my Sportsman class car: to Alabama for Huntsville Thursday night, Birmingham Friday night, back to Tennessee for Nashville Saturday night, Owensboro Sunday night.

“Stevie and I did everything together, and she always came to the races in the truck. But in those days ladies weren’t allowed in the pits. So I bought her an owner’s licence, said the car belonged to her and then they had to let her in. She was the only woman on pit road. She used to calculate all my gas mileage, and she was real smart at it. One day Jake said, ‘We’re never gonna win a race as long as That Woman is in our pit.’ It was close to race time, and I said, ‘Hey, Jake. We got a 22-gallon fuel cell, we’re getting 4.54 miles to the gallon, how many laps can we go on a tank?’ He thought for a moment, and then he said, ‘Go get That Woman’.”

***

By now Darrell had the reputation for being the bad boy of NASCAR. “I didn’t mean it that way. It seemed like I talked a lot, but it was because the other guys didn’t talk any. They reckoned they owed their livelihood to [NASCAR boss] Bill France, and they never wanted to say anything out of turn. So the media had trouble getting any of them to say anything. But I understood that the media could work for me. If you wanted to tell Bill France you thought the rules were screwed up, he’d never have time to speak to you. If you told the press and it was in the papers next morning, he’d be on the phone by 10am.

“And I’d poke fun at some of the other drivers, just winding them up. They’d say – and the fans would say as well – Waltrip’s arrogant, he’s obnoxious. But it all got written up, and the promoters loved it. Like I said that Petty (who was 10 years older than me) needed a new prescription windshield. Richard didn’t think it was funny. I was just showing off, I guess. Nobody else was doing it, so I ended up with that role.

Battling with Dale Earnhardt Jr at Indy in 2000, Waltrip’s last racing campaign

Motorsport Images

“By 1974 my little rag-tag team was beating a lot of the big teams with all their dollars, fancy cars and fancy-smancy haulers. Donnie Allison, Bobby’s brother, was driving for Bill Gardner’s DiGard team, and Gardner had a big ego. At the 1975 Daytona Firecracker 400 I passed Donnie on the last lap to finish third. After the race Gardner said to his brother Jim, who worked in the team, ‘Hire that boy. I’m tired of the little sumbitch outrunning us every week.’ So they fired Donnie there and then, and Jim came after me, said Bill wanted me and would pay me good. I said, ‘I don’t see how I can do that. I’ve got cars, I’ve got commitments.’ When I told Stevie she said, ‘Are you out of your mind? We’re broke, we’re spending money we don’t have, and they’re going to pay you to drive?’

“So in the end we did a deal whereby DiGard used my cars, and all the good people I had working for me came with me. We won a bunch of races in ’77 and ’78, should have won the title in ’79, and we led it for most of the season. But I blew it at Darlington. Pearson was the local hero there. They said, ‘Ain’t nobody can beat Pearson at Darlington.’ Well, I was leading him by a lap. My guys were signalling to me, ‘Take it easy, stroke it home,’ but my ego got in the way. I wanted to put him down. Then, lapping another car I got high on the loose, and I put it in the wall. Pearson won the race.

“After Darlington things started to go downhill between me and DiGard. The team were mad at me because I didn’t listen, I was mad at them because they were mad at me. At Wilkesboro Donnie got his own back, hooked me into the fence. At Ontario there was a big coming together mid-pack, cars spinning everywhere, and I had to spin to stay out of it. So Petty pipped me to the title.

“In ’80 I won five rounds. One of those was Riverside, which was something else because it was a road circuit. Back then we didn’t build special cars for the road courses, we just set up the same cars a bit different so they could turn right. Plus you had to slow down for corners, and you had to change gear! Everybody would run out of brakes and tear up clutches and gearboxes, so the secret was to take care of your car. Those old top-loader Ford gearboxes were like driving a damn truck, by the end of the race your right arm would be about broken.

“By now I wanted to move on from DiGard. Bill Gardner wasn’t a racer, he was a businessman. Before him everything was done on a handshake, and if you got mad, I’m tired of you, I don’t like your crap, you walked. Gardner gave you a contract thicker than a book. That set everything, down to when you were allowed to go to the bathroom, and how often. For 1981 he wanted to renew my contract for another five years. I was getting expenses and 40 per cent of what I won, so I told him I wanted expenses and 50 per cent. We argued back and forth, and then just before a race he brought me a new contract on pit road as I was about to get in the car. He said I had to sign it now, and told me everything I’d been asking for was in the contract. So – young, naive – I signed it, and got in the car.

“When I went into the shop the following Monday the finance guy said, ‘I need your team credit card back.’ Whaaat? How was I going to pay for my hotel and rental car at races? He said, ‘The new contract got the 50 per cent you wanted, that was in lieu of your expenses.’ I didn’t even know what ‘in lieu of’ meant.

“And now I was locked in for five years, and I wanted out – particularly as Junior Johnson wanted me to drive for him for 1981, with Pepsi sponsorship. In the end I had to buy myself out for $350,000. I paid $150,000, Junior paid $100,000, Pepsi paid $100,000.”

***

Junior Johnson was, and in his mid-80s still is, one of the legends of NASCAR. His father was a lifelong bootlegger in rural North Carolina, and totted up nearly 20 years in prison. Junior ran illegal whisky too: the federal agents chased him on the dirt backroads but they never caught him, although he did serve one term in jail for having an unlicensed still. The movie The Last American Hero is based on his life. He graduated from moonshine to NASCAR, and won 50 major races before hanging up his helmet to become a team owner. He had already won three championships with Cale Yarborough before Darrell joined him.

“All the time Cale was driving for Junior we were rivals, but we liked each other. Wreck each other on the track, buy each other a beer afterwards. In May of 1980 he took me to one side and said, ‘Keep this to yourself. I’ve decided to leave Junior at the end of the year. I haven’t told him yet, but I know he’d like for you to drive his car. With Junior you’ll win more races and make more money than you’ve ever done in your life.’ So in due time I let Junior know I wanted out of DiGard, and we went from there.

“This time I made sure I had an attorney when I signed for Junior. He brought his attorney, four of us sat down, Junior produced one sheet of paper. All it said was: ‘You drive for me, for this many years, I’ll pay you this much.’ My guy says, ‘There’s nothing here about what bonus you’ll give Dee-Dubya if he wins the championship.’ Junior growls, ‘Let me tell ya what I’ll give him if he don’t win the championship!’

“But I still had a bad reputation, and I needed to fit into Junior’s team. There was an old guy who did their cylinder heads named Bill Alman. He told everyone he didn’t want anything to do with that dumbass from Tennessee, all he ever does is run his mouth. I knew that if I was going to fit into that team, I had to make friends with Bill.

“So I went to the shop, he was grinding away at an inlet port, and he growled at me: ‘You the sumbitch gonna take Cale’s place? You don’t look like much.’ I said, ‘I think I can drive pretty well.’ He said, ‘You ever drink any moonshine?’ ‘No sir, I never did.’ ‘Well, you and me is gonna have a little drink.’ And he got out of his toolbox a jam-jar full of completely clear liquid and took a swig of it.

“I was holding a styrofoam cup of coffee, so I emptied out the coffee and he poured in a big slurp of this stuff. I’m sniffing it and thinking, ‘This is going to hurt,’ and meanwhile Bill’s chugged about half the jam-jar. So I grit my teeth and get ready to take a sip – and the bottom falls out of my cup. It had burned straight through the styrofoam. That cracked him up, and after that we were pretty good buddies.”

***

That was the start of a magic period for Darrell, and over the next six seasons he won 43 major races for Junior Johnson. He was NASCAR champion in 1982 and again in 1983. In 1984 came a horrifying accident at Daytona, when a slower car got in his way. He went backwards into the inside earth bank at nearly 200mph, bounced back into the path of the following cars, and then hit the outside concrete wall. He was dragged from the wreckage unconscious.

“After a check-up I got myself out of hospital, and I raced in the Richmond 400 the following week. And the week after that was Rockingham. The Wednesday after Rockingham I was sitting at home, and suddenly it was like I had just woken up. I had no memory at all of the past two weeks. I’d raced at Richmond, I’d raced at Rockingham, and I didn’t remember any of it, not a clue.” But there were six more wins that year, leaving him runner-up in the championship. He was champion for the third time in 1985, and he was runner-up again in 1986.

Darrell also had the chance to try a completely different discipline when he drove an Aston Martin Nimrod in the 1983 Daytona 24 Hours. “Bill France set it up. The car needed three drivers. A British guy called Tiff something [Needell] was one, and they said, ‘Who do you want for your other co-driver?’ So I gave old AJ [Foyt] a call. AJ said, ‘No way am I gonna do that nonsense.’ So I called Pepsi, my NASCAR sponsors, and got them to come up with $10,000. I called AJ back and I said, ‘I’ve got you ten grand.’ He said, ‘I’ll do it.’

“The car was a big heavy old thing, and the first problem was it was on Avon tyres. AJ said, ‘I can’t drive it, I’m contracted to Goodyear.’ So they put it on Goodyears. The race started, AJ was running fifth when a wheel started to fall off, tore the bodywork, and that put us in the pits for a long time. I took over, got it back up to seventh, and then the oil light came on. I stopped, sat strapped in while they worked under the hood. AJ came over and whispered to me, ‘Get outta the car, Dee-Dubya. It’s going to blow up. Put the foreign guy in.’ But Tiff never went out, because they retired the car. So AJ just wandered off down to Preston Henn’s pit, got in their Porsche 935, and won the damn race!”

***

As a triple NASCAR champion, Darrell was now hot property. “But I was also about to be 40. Junior never made it a secret that he preferred young rising talent over long experience. On the side I now had a Honda dealership with Rick Hendrick, who had a string of car businesses and also ran a top NASCAR team. He’d landed a new sponsorship deal with Tide, the detergent brand, and suddenly he approached me with an offer to drive for him.

“Well, Junior was paying me $150,000 a year plus half my winnings. Rick wanted to pay me $500,000 a year plus half my winnings. I still felt loyalty to Junior, but when I told him about Rick’s offer he grunted: ‘Boy, if some damn fool wants to pay you that kind of money, you’d be a damn fool not to take it’.”

Darrell’s first two seasons with Hendrick were difficult, with only three wins, but in 1989 things came alive. “I started the season by winning the Daytona 500: I had a clever fuel strategy and managed to make one stop fewer than everyone else. Then I won Atlanta, I won Martinsville.

“But in the big-bucks All-Star exhibition race the day before the Charlotte World 600, I was leading and Rusty Wallace came in hard, hit my left rear and spun me out in a cloud of rubber smoke. Well, the stands went into uproar, the fans were booing and throwing garbage onto the track. It all got a bit violent, and Rusty was smuggled out of the track lying on the floor of a police car. The phone switchboard at the track received death threats against him, and the FBI had to put a guard on his house overnight. And next day I won the World 600.

“That weekend was kind of a turning point: it was when everybody stopped hating me and started hating Rusty.

“In 1990 I had a big wreck testing at Daytona. A car in front blew its rear end, sprayed oil everywhere, I spun, and I was T-boned in my driver’s door by the next car along, which was doing 160mph. Once they’d got me to hospital and got me sorted out – smashed femur, broken arm, broken ribs, concussion – they said it would be at least six months before I could race again.

“But as far as I was concerned the season was still in full swing, and 10 days later I had to be at Pocono. To stay in the hunt, I had to start that race. If I could do at least one lap, and then hand over to a relief driver, I would take whatever points the car earned.

“I was in really bad shape, but I got a specialist to make a removable cast for my leg, and my crew practised putting me in and out the car, shooting me through the window like a log. Once I was in I could just about drive the car. The race stewards agreed I could do one lap at the back, which I did, then I came in. My relief driver Jimmy Horton was standing by, they pulled me out through the window, and Jimmy took over and finished the race.”

At the end of that season Darrell left Hendrick to set up his own team. “I made two bad decisions in my career. One was leaving Junior. The other was leaving Rick. Rick had allowed me to do my own thing, I had my own people and we were building the cars. But I convinced myself I could spend Tide’s money as easy as Rick could. And it’s one thing to win a race as a driver, it’s something else when you win in your own car. So I thought, why not?

“But that’s when I got hurt. Tide stayed with Rick, and I had a struggle to find another sponsor. In the end I signed Western Auto, a car parts company, for $3 million a year. That wasn’t a lot – but at least I didn’t need to pay my driver.

“And with Darrell Waltrip Motorsports we had six good years, scored some more wins, and we ended up with a successful truck racing team too. I took on my own engine programme, and with all the endorsements and souvenirs and everything I was making enough money to keep the team running at a pretty good level.” He also had a lucky escape during another massive accident at Daytona after contact within a tight 190mph group. His car cartwheeled repeatedly end-over-end, but Dee-Dubya emerged from the wreckage with only slight injuries.

“Then Western Auto got taken over, and they pulled out. Meanwhile costs in NASCAR suddenly seemed to be galloping. I’d started with 12 people but now, with the engine shop, the truck team, everything else, I was employing 60 people. Running the whole outfit was costing me $600,000 a month. My 1998 sponsor, a building firm called Speed-Block, defaulted on what they’d contracted to pay. So I was in trouble, and I had to accept the grim truth: the only solution was to sell the team.

“There was a guy from Tyler, Texas called Tim Beverley, whose business was selling pre-owned aircraft. He flew in, I showed him around, and going back to the airport he said, ‘How much do you want?’ Well, $4.5 million seemed like a good number to me, so that’s what I told him. When he said, ‘I’ll take it’, I wished I’d said $6 million.” A few years later Beverley served a substantial jail sentence for a $20 million bank fraud.

Darrell continued to race for other teams, including 10 races for the outfit run by his former bitter rival Dale Earnhardt, before finally hanging up his helmet in 2000 at the age of 53. “Right away two TV companies covering NASCAR came after me because they knew I liked to talk. A guy from NBC flew in, I told him what I’d like to be paid, and he choked and said, ‘Son, nobody starts at that level,’ and flew home. Then a crazy Australian from Fox named David Hill got in touch. We spent a fun day together, and as he was leaving he pulled out of his pocket a piece of paper. At the bottom was a figure double what I’d asked for from NBC.

“My first race as a Fox commentator was the Daytona 500 at the start of 2001. Before the race I interviewed Dale Earnhardt: my rival, my enemy and my friend for nearly 30 years, seven times NASCAR champion and one of the all-time greats. He was relaxed, happy, at the top of his form, and we had some good banter.

“When Dale and I first raced against each other both of us always felt, ‘If I can’t win, you’re not going to win.’ There weren’t big salaries, big motorhomes, private planes. This was survival, man, you were racing to put food on the table. If he beats me, he’s going to be eating steak, and I’m going to be eating baloney. You couldn’t be friends with somebody and compete against him every weekend.

“But behind all that there was respect, respect on both sides, and when he asked me to drive for his own team in 1998 we mended bridges, we worked out a lot of things we’d been angry about. I was pretty much broke at the time, and he paid well, treated me well. I hadn’t been having good results, people were saying I was too old, I was washed up, I should quit. But Dale loved proving people wrong, and he gave me my confidence back.”

Come that fateful 2001 Daytona race, in the closing stages the battle at the front was between Dale, his son Dale Jr and Darrell’s younger brother Michael Waltrip – all three driving for the Earnhardt Chevy team – plus the Dodges of Sterling Marlin and Kenny Schrader. In the final turn of the final lap, Marlin and Earnhardt touched. Earnhardt careered up the banking, cannoned into the wall and was then hit by Schrader. Ahead of the chaos, confusion, wreckage and tyre smoke Michael Waltrip took the flag from Dale Jr.

“I was whooping with delight, describing in my first race commentary my brother winning the finest victory of his career. But I knew Dale’s accident was bad. When you hit that wall it’s like you’re shot out of a cannon, and then he also had the force from the side when Schrader hit him. I saw Schrader run over to Dale’s cockpit, then I saw him jump back. That’s when I knew it was bad. And once they got him in the ambulance it didn’t hurry, it drove off at 20mph. I knew then that Dale was dead.

“I would have gone straight to Victory Circle to congratulate Michael, but as we wound up the TV coverage a police escort arrived to rush me through the crowds to the hospital.

“I won’t go into the detail of what happened after that, but once I’d got over my initial shock and grief I was angry. The HANS device (head and neck support) was available then, but NASCAR hadn’t made it mandatory. Dale certainly wouldn’t wear it from choice – he didn’t even wear a full-face helmet. But over a few months we’d lost Adam Petty, Kenny Irwin, Tony Roper, all from basilar skull fractures in the same type of impact. Almost certainly the HANS would have prevented all those deaths.

“I talked about this a lot on TV, I even demonstrated the device on-air, and I argued passionately with Bill France and other NASCAR officials about their responsibilities for driver safety, which didn’t make me very popular. They still insisted that the driver’s environment had to be up to the driver.

“Then in an ARCA-sanctioned race that October, Blaise Alexander died from a basilar skull fracture. Within days of his funeral, NASCAR announced that henceforth the HANS device would be mandatory.

“Now I’m no longer a racer, I’m busier than ever. And I’m living in the real world now. When you’re a driver you’re spoiled. People get your helmet for you, get your goggles and gloves, get a bottle of water for you, drive you out to your private plane. They’re always there to kiss your butt. That’s not the real world.

“Actually when I was racing I did my best to keep my feet on the ground. I never collected memorabilia, and I gave away all my helmets. I never kept my trophies, either. I always gave them to the guys on the team who did the work. If someone had worked all night building my engine, and I won the race and got the glory, he deserved the trophy more than I did.

“I just know how blessed I was, to be able to race all those years and then step out of the car straight into the commentary booth. This is my 16th season as a TV analyst, but it’s also my 53rd year of being involved with car racing. I guess you don’t get much more blessed than that.”