Grey area over 1912 Sunbeam racers

The question of sources has a topical ring to it. My announcement that all three of the racing Sunbeams which in 1912 finished 1-2-3 in the Coupe de l'Auto race…

How high is a mountain? Our definition – anything over 1000ft – pales into foothills compared with mainland Europe, and the same thing applies to hillclimbing. That doesn’t make our 1000-yard dashes easy, but tell an Italian hillclimb champ that the record on our shortest hill (Barbon, Cumbria) stands at 20.08 seconds and he’ll think you’ve left out the minutes. Swiss Alps, Italian Dolomites, French Massifs – all have played host to car challenges which in scale tower over ours, and once drew racing’s greatest stars.

People have been pitting cars against gravity since Queen Victoria’s time. La Turbie, now better known as a rally stage, was part of an event in 1897 while in 1898 a true hill-climb took place at Chanteloup-les-Vignes near Paris. Petersham Hill near Richmond-on-Thames held Britain’s first uphill trial in June 1899 and of course Shelsley Walsh began in 1905. But these pioneer events set a style: cramped by laws forbidding racing on public roads, Britain would settle to short, steep sprints on private ground while other European nations were happy to close roads and would eventually even have grand prix cars extended on mountain slopes. The scenic spectacle we couldn’t approach: the feared Grössglockner climb gained 4500ft in height – and that’s a whole Ben Nevis-worth.

For a space between the wars hillclimbs carried similar weight to grands prix, and place names such as Klausen and La Turbie were coupled with the names of Caracciola, Nuvolari, Pintacuda, Lang and Stuck. Large crowds sat down on rocky hillsides to watch local heroes and star names attack roads which carved their way bend by tortuous bend up to cold and lonely summits – where they had to wait until everyone had run and they could motor down.

Maserati, Alfa Romeo’s Scuderia Ferrari and later the works Auto Union and Mercedes teams treated hillclimbs as highly prestigious, even building special uphill variants of their grand prix racers. But once war disrupted competition, hillclimbing and racing came to occupy increasingly separate worlds.

In early years endurance events such as the Prince Henry trials in Germany included daunting ascents, but hillclimbing really took off after WWI, often on roads which would themselves become legends – Italy’s Stelvio Pass with its 46 hairpins, or Mont Ventoux, the ‘Giant of Provence’. Over cobbled or unpaved roads with little protection from a fearsome drop, these were challenges of skill, bravery, and of memory too.

These events attracted all types of vehicle: in 1923 René Thomas took the course record at the Gaillon climb in the 10.5-litre V12 Delage which later broke the Land Speed Record, while through the 1920s Mercedes employed modified 1914 2-litre GP cars, Rudi Caracciola conquering the Semmering climb in 1926 and Adolf Rosenberger scoring FTD at Freiburg and Klausen. From 1921 on the Klausenrennen became seen as one of the great tests, the Nürburgring of hillclimbing: 13½ sinuous miles winding upward along a mountainside, through multiple hairpins alternating with open stretches past Alpine farms, one of them a 2½-mile near-straight where cars came fearsomely close to top speed. Much of it was unsurfaced, with only stone pillars to fend a driver off tumbling disaster. In 1926 Motor Sport called it “the greatest hillclimb event in the world” with “almost the status of a grand prix”, so Britain was aware of what was happening over the channel, although Europe’s top runners had no incentive to ferry their beasts over here to tackle 1000 yards of Shelsley. But that was about to change.

In 1930 the AIACR (the FIA of the time) created a championship out of this demanding arena. Already the sport had its specialists – Hans Stuck in an Austro-Daimler for one, and British enthusiasts, excited to find that short, sharp Shelsely Walsh was part of the new series, were thrilled when the German bergkönig (king of the mountains) arrived with his 3½-litre machine and slashed the Worcestershire hill record. His terrific speed, we said, “made even hardened spectators sit up”. Fastest sports car was “the famous Caracciola” in a Mercedes 38-250, a sign of the attention the Stuttgart firm under Alfred Neubauer was devoting to developing its SS and SSK models on hills as well as track. Incidentally, the round after Shelsley was Klausen, 24 times the length…

With an initial 10 varied rounds, the European Hillclimb Championship briefly seemed a parallel to grands prix, with many of the same cars contending. In Italy’s lengthy Trieste-Opicina climb wiry Mantuan wizard Tazio Nuvolari brought newly-formed Scuderia Ferrari its debut victory, first of three in a row in Alfa’s P2 GP car, but during that first year Stuck confirmed his mountain-king title, Caracciola heading the sports car class. Through 1931 the lighter SSKL brought ‘Carratsch’ a second cup, though Austro-Daimler pulled out of racing. But while the championship showed how many climbs there were in Europe, the number of events quickly dropped and the buzz around the title declined. Individual meets had more pull than points-scoring. In addition economic woes stopped Mercedes competing, leaving Caracciola as a semi-independent driving a Tipo B Alfa. Stuttgart would return with a higher aim in view, alongside another German contender currently girding its silver loins…

All this meant privateers could enjoy their 15 minutes of uphill glory: in 1933 British-based American Whitney Straight took his 8C Maserati to Mont Ventoux, fitted twin rear wheels and in front of a huge crowd on this classic hill smashed Caracciola‘s Alfa Romeo record by an astonishing 40 seconds. “All those present,” said Motor Sport, “were absolutely dumb-founded”.

Italy had her star too, in wealthy amateur Mario Tadini – a mid-fielder on the track but an ace on a hill, master of the Stelvio and on his day able to beat Nuvolari. He was 1933 European hill champion, but that was the last of the EHC. Conflicting rules cut the season to four events. Nevertheless, hillclimbing remained a hugely popular spectacle, and new drama was warming up in the workshops.

In a silver blaze of excitement, in 1934 Mercedes revealed a grand prix car of astonishing sophistication built to the new 750kg formula; so did aspiring new marque Auto Union. Both would pit their staggeringly powerful machines against the hills: spectators were about to witness great things.

“Motor Sport called Klausen ‘the greatest hillclimb in the world’”

Klausen Pass, August 1934, the 10th International meeting. Shrouded in rain and gloom, drivers mutter under umbrellas in the makeshift paddock. Snow has thankfully turned to rain, but now there’s a threat of flooding across the course and a rockslide has blocked the straight where cars should be at full throttle. Mercedes, Auto Union and Maserati works teams are here with their grand prix cars; Hans Ruesch, Tufanelli, Whitney Straight are in the unlimited class with Alfas and Maseratis. Penn Hughes and Hugh Hamilton are notable among the Brits, along with Eileen Ellison, who has camped alongside her Type 37A Bugatti.

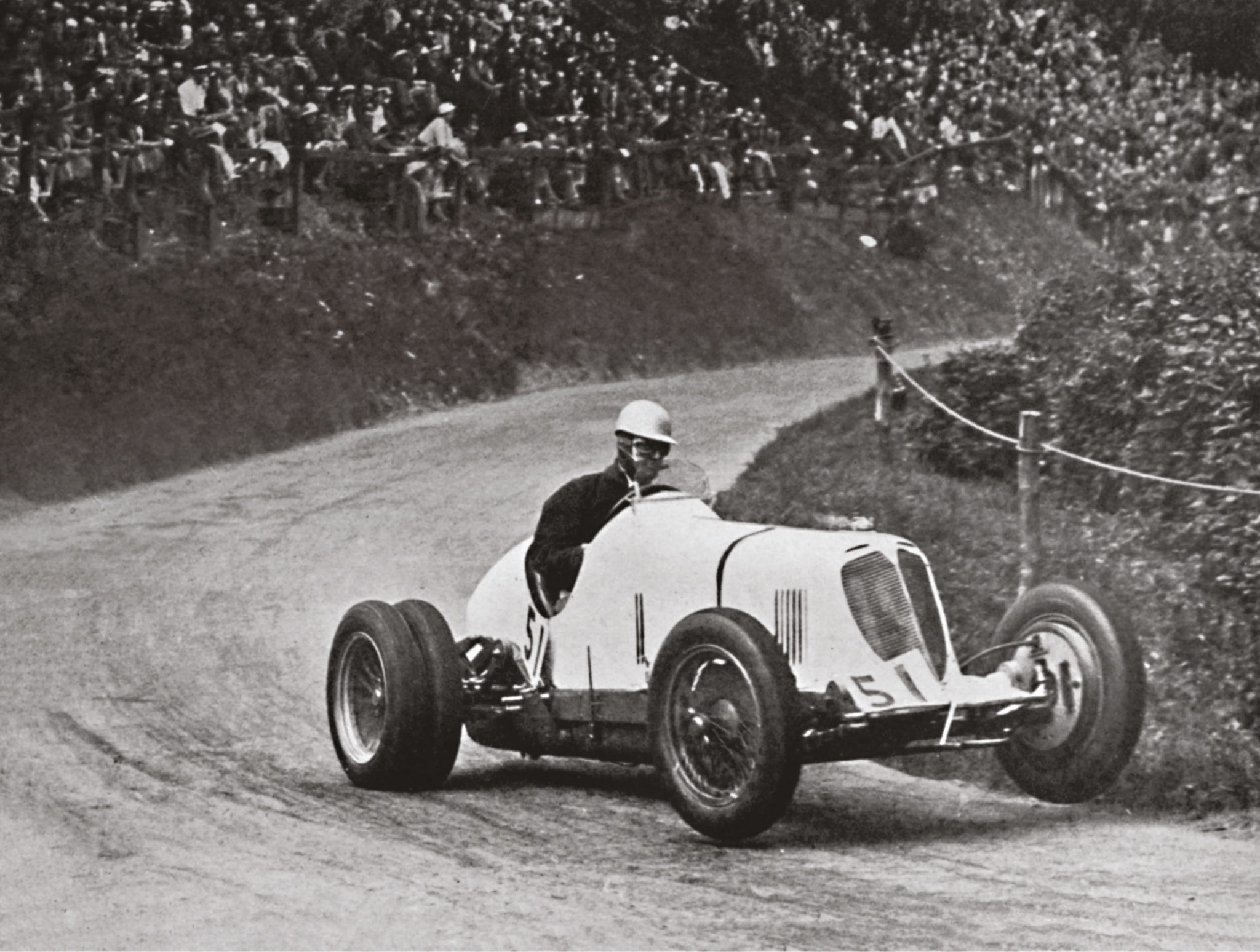

No sign of the innovative 4WD Bugatti 53 that lifted René Dreyfus to a recent record at La Turbie, nor Alfas for Achille Varzi and Louis Chiron, despite a good year for the Scuderia. Everyone is watching the two German stars: Caracciola in his supercharged straight-eight W25 and Stuck, crammed up by his Auto Union’s front axle to make room for fuel and the lengthy blown 4.4-litre V16 behind. As the weather improves the smaller classes set off, Bugattis and MGs scattering gravel on the unsurfaced course. Slowest of all, a Derby takes a laborious half an hour. Finally the big moment: stones shower as Caracciola’s thin tyres struggle to put down 354hp, the barking Mercedes slithering out of each gravelly hairpin, every stone pillar ready to snatch a wheel and flick him down the scree slope. Then the chance to hit top gear and nearly 160mph on the straight before the last curves. It’s an awe-inspiring sight, and sound, excitedly captured by Pathé News: “Caracciola‘s car nearly flies off the handle as he rounds these bends!”

If anything Stuck’s effort looks more impressive, fighting the engine’s efforts to turn him round on every bend, huge four-spoke wheel whipping lock to lock as he balances power against inadequate grip. As you’d expect from the king of the hills it’s masterly, but one bend brings a huge slide until, broadside, Stuck has no more lock left. Then the tall tyres bite, the car straightens and surges forward. But it’s not enough: Caracciola has broken the record with 15min 22.2sec, Stuck 3sec behind. It’s one of the great moments, and swamped by a huge wreath the cherubic German beams as he accepts his trophy. His hill average is under 60mph; months later he will touch 197mph in a streamlined version of the same model.

Though the EHC had gone, national series continued. In 1935 a dramatic new road was opened over Austria’s towering Grössglockner Pass and within days it was the scene of a new hillclimb, requiring over 90 gearchanges. It proved a disappointing meet – it poured with rain and the German teams failed to show, leaving the field to Tadini’s Alfa Romeo. Close behind came a young Britisher called Richard Seaman in his black ERA. One month later on the 12km Freiburg climb (“regarded as a grand prix”, said Motor Sport) he would score another second, to Stuck’s 5-litre B-type Auto Union. That did not go unnoticed. Grössglockner did not host another climb until 1938, and by then Seaman would be in white Mercedes overalls.

“Mercedes prepared three special machines for 1939. The mountain business was that important”

The next time Auto Union competed would be notable too – for the wrong reasons. On Italy’s Stelvio Pass Tadini cemented his reputation by ascending the zig-zag rise 17sec faster than the supernaturally talented Nuvolari in a similar Tipo B. Meanwhile, we reported that “the miserable Varzi” had “a tough job taking the long German car to the top. The Auto Union was hopeless on the hairpins, and he had to reverse on five of them. His discomfiture delighted the Italian spectators, who loudly proclaimed the virtues of the Alfas and Maseratis. So offensive did their demonstration become that the announcer appealed for sportsmanship.”

By now German machinery had such a hold on this arm of the sport that the Deutsche Bergmeisterschaft, centred on prime climbs at Freiburg, Feldberg and Kesselberg, was pre-eminent, crowning home winners as de facto European champions. Stuck paid his famous visit to Shelsley with a short-chassis twin-wheeler, but 1936 brought a hillclimbing slump as events were cancelled; Mercedes struggled with its latest W25 and Bernd Rosemeyer snatched Caracciola’s European drivers’ title and took team-mate Stuck’s mountain crown with victory at Freiburg.

With the new 3-litre grand prix formula of 1938 the big cars were redundant – but not in hillclimbing, which was effectively unlimited. Those long mountain tests still offered a perfect backdrop for the display of German might – now echoing to more sinister power. The Grössglockner would run again – as part of the German series. Austria had now been subsumed by the Hitler regime.

Perhaps learning from the Stelvio, Auto Union brought a short-chassis C-type 6.1-litre V16 hillclimb special, and on a shortened rain-soaked course run in two heats Stuck defeated the Mercedes W125s of Walther von Brauchitsch and Hermann Lang. Herr Seaman declined to compete due to the road state.

Stung, Mercedes prepared three special hillclimbers for the 1939 event, all with narrow front brakes and glycol cooling, their radiators rear-mounted for traction: one lowline 3-litre V12 154 (Lang had already won the Vienna Höhenstrasse climb in one) plus a pair of W125s enlarged to 5.66 litres. The mountain business was that important.

Even on this eve of war the entry was packed, and heavy rain did not stop 30,000 spectators lining the bends to the gloomy summit. After practice both Lang and von Brauchitsch chose the older straight-eights, ignoring the available twin wheels as being too wide, but it was Hermann Müller’s Auto Union which triumphed in the first heat. Perhaps Stuck wasn’t invincible. Now thunderstorms and fog took a hand, slashing visibility. In the awful conditions no-one could match Müller’s best, but a multiple spin in heat two lost him 23 seconds, handing this last hillclimb crown of a great era to Mercedes and Hermann Lang. Stuck finished third.

After the war hillclimbing in Europe created new championships, sometimes contested over the fabled climbs of the 1930s, and new hillclimb aces. But while the grand prix world occasionally looked in – Porsche’s 804 at Ollon-Villars in ’62, Jim Clark’s Indy Lotus 38 three years later – the two disciplines increasingly diverged.

You can still experience what whole glorious minutes of petrol-powered Alpinism looks and sounds like – with many venues dotted around Europe where today’s inheritors of the tradition chase uphill glory. Just don’t expect to see Vettel or Verstappen standing around on a chilly mountain top waiting for the downhill return.

Current climbs to watch, plus defunct ones to drive

France St-Jean-du-Gard-Col de St-Pierre

Date 13-14 April 2019 Length 3.1 miles Average speed 84mph Entry Sports-racers, single-seaters, road cars Nearest town Alès Nearest airport Montpellier. www.asa-ales.fr

Part of both French and European hillclimb championships, this climb starts with a series of hairpins opening into a faster section above a valley, with some alarming drops on the way to the Col de St Pierre finish. Contenders range from Osella-Judds to classic Simcas. Set in the beautiful Cevennes National Park, castles and ruins abound, while a historic train from Anduze to St Jean du Gard offers the perfect way to view the mountainous landscape. Then head north to Florac with its C12 château, or west to the dramatic Gorges du Tarn.

Czech Republic Ecce Homo Šternberk

Date 1-2 June 2019 Length 4.8 miles Average speed 104mph Entry Sports-racers, single-seaters, FIA Historics Nearest town Sternberk Major airports Vienna, Prague. eccehomo.cz

Gaining its name from a statue of Jesus on a nearby peak, the annual Ecce Homo climb winds through dramatic volcanic scenery in Moravia. Cars start in Sternberk town, through hairpins to fast, open reaches toward the finish. Even the quickest cars take over five minutes. EHCC and FIA Historic round. Fly in to Prague or Vienna and enjoy those grand capitals but don’t miss Olomuoc, 10 miles away, destroyed in the Thirty Years War but rebuilt in baroque style and boasting the 115ft-high Holy Trinity Column.

Italy Trento-Bordino

Date 6-7 July 2019 Length 10.6 miles Average speed 71.4mph Entry Sports-racers, single-seaters, historics Nearest town Trento Nearest airport Milan, Venice. scuderiatrentina.it

Longest active climb in Europe, up the shoulder of Monte Bordino through bends too bewildering to count. But the route slices through villages on the way, so grab a seat at a bar or restaurant with a view of cars flying past drains and doorsteps. But once you’re there you’re staying until it’s over. Combined EHCC and FIA Historic round. Nearby Trento boasts medieval frescoes and Renaissance buildings among fabulous scenery. Lake Garda is an hour south, with historic Vicenza, Verona and Brescia easily reached.

France d’Etretat Bénouville

Date 25 August 2019 Length 1 mile Average speed 81mph Entry Sports, single-seaters, road cars, classics Nearest town Etretat Ferry services Caen, Le Havre, Dieppe. asacotedalbatre.com

European hillclimbing isn’t all long mountain ascents. France has a healthy range of short British-style climbs. Popular with Brits, the friendly event at Etretat between Le Havre and Dieppe has classic cars mixing with F3 Dallaras above a pretty seaside town set between towering cliffs. With a rise of 164ft it’s not so much a hillclimb as a canted sprint, but an excellent excuse for a Normandy excursion. Take the ferry to Caen, exploring ancient Bayeux and the D-day relics at Arromanches. Don’t miss medieval Honfleur.

Switzerland Ollon-Villars. Ended in 1971 but was very popular with Brits including Patsy Burt, Innes Ireland, Jim Clark. Retro event due in 2020.

Switzerland Klausen Pass, Glarus. Classic climb and superb driving road, surprisingly unspoiled thanks to newer alternative route nearby.

France La Turbie, Nice. Legendary ascent, still a stage on Monte Carlo Rally and Tour de France, passing super-quaint Ezé with Riviera backdrop.

Italy Mont Cenis, Susa. First run in 1902. Take the Col du Mont Cenis route out of Italy and drive in the tyre tracks of Nazzaro, Campari and Varzi.