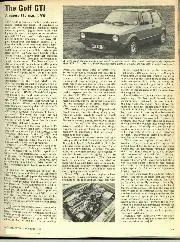

The Golf GTI

A superb 110 m.p.h. VW The art of civilising the high-performance engine reaches new heights of excellence as each year of increasingly regulation-bound motoring passes. Jaguar have taken such high-performance…

RECENT war laws and activities seem to be causing some unnecessary worries. Immobilisation, for instance. It is perfectly logical to suppose that paratroopers might try to seize cars and to immobilise accordingly. If they have managed to hold up the advancing L.D.V. Corps and troops, they will have time to uncross plug leads and stick wires back into coils, and find substitutes for ignition keys. Something more drastic is called for, the easiest of which seems to be to remove the distributor rotor. This has given rise to terrible tales of police who see a key in place or a door unlocked and either let all the air out of the owner’s tyres according to one school, or waste hours standing guard, according to another. Extremists tell of further bits of machinery being removed by the police, although official instructions suggest that this is not encouraged unless a police mechanic is consulted. Surely, in the ease of all open car when a bit of engine must be detached, the logical procedure is to leave the ignition key in place, so that any doubting constable can spin the engine on the starter to make sure it has been immobilised. If steering, gear-change or road wheels have been locked this should be evident, and the only possible snag might concern a locked fuel tap, when the engine might start up on the float chamber contents, and run long enough to give the impression it was not immobilised. So open-car owners should not need to worry over what is, after all, a sensible regulation. Nor can we imagine the police tampering with any closed vehicle of which the doors are locked and the ignition key removed. Quite how a girl of fourteen will combat a desperate paratrooper, or how just locking up a saloon will prevent such a gentleman from smashing a window and using a skeleton ignition key to get away, I cannot see. Nor can I quite comprehend why the law looks at private cars and conveniently forgets other vehicles. I hope conscientious motor-cyclists will devise their own immobilisation schemes, and I hope that pedal cycles left un-attend for long periods will be placed under lock and key.

The ban on purchase of new cars without licence, which came into force on July 20th, may well stimulate the used car business. If you hardly agree, may I remind you that new car registrations have averaged over 3,000 a month since war began, and that the figure for May was 3,603? Although this represents a decrease of 24,665 over May, 1939, it does show that there is still an appreciable buying public left, which must now look to the secondhand market to meet their requirements. Properly re-conditioned used cars may well be in steady demand, especially as basic and supplementary fuel rations are assured up to the end of October.

This voluntary offering of aluminium wear is highly commendable, but the piles of ancient pots and pans, and the truck-loads of brass-knobbed bedsteads you see about, look a little lonely beside the acres of old cars that still occupy breaker’s premises. I realise that good money will eventually have to be paid for this metal, whereas the pots and pans are gifts from patriotic housewives. However, it occurs to me that probably quite a lot of garages and secondhand traders would willingly give away at least one old car apiece, perhaps as some return for having been granted extra petrol, and given, in some cases, useful Government repair contracts. If a band of enthusiasts went round asking to be allowed to tow away such cars and break them up in some appointed place, so that the aluminium, iron and steel thus recovered could be deposited in local scrap collections in convenient form, I think quite a reasonable response would be forthcoming. Doubtless, extra petrol would be willingly granted by local authorities to the tow-car, and this seems a chance for club members, especially in country districts, to have some fun and do good work of National Importance at one and the same time. Moreover, they could be relied on to spare good motor cars and real veterans . . .