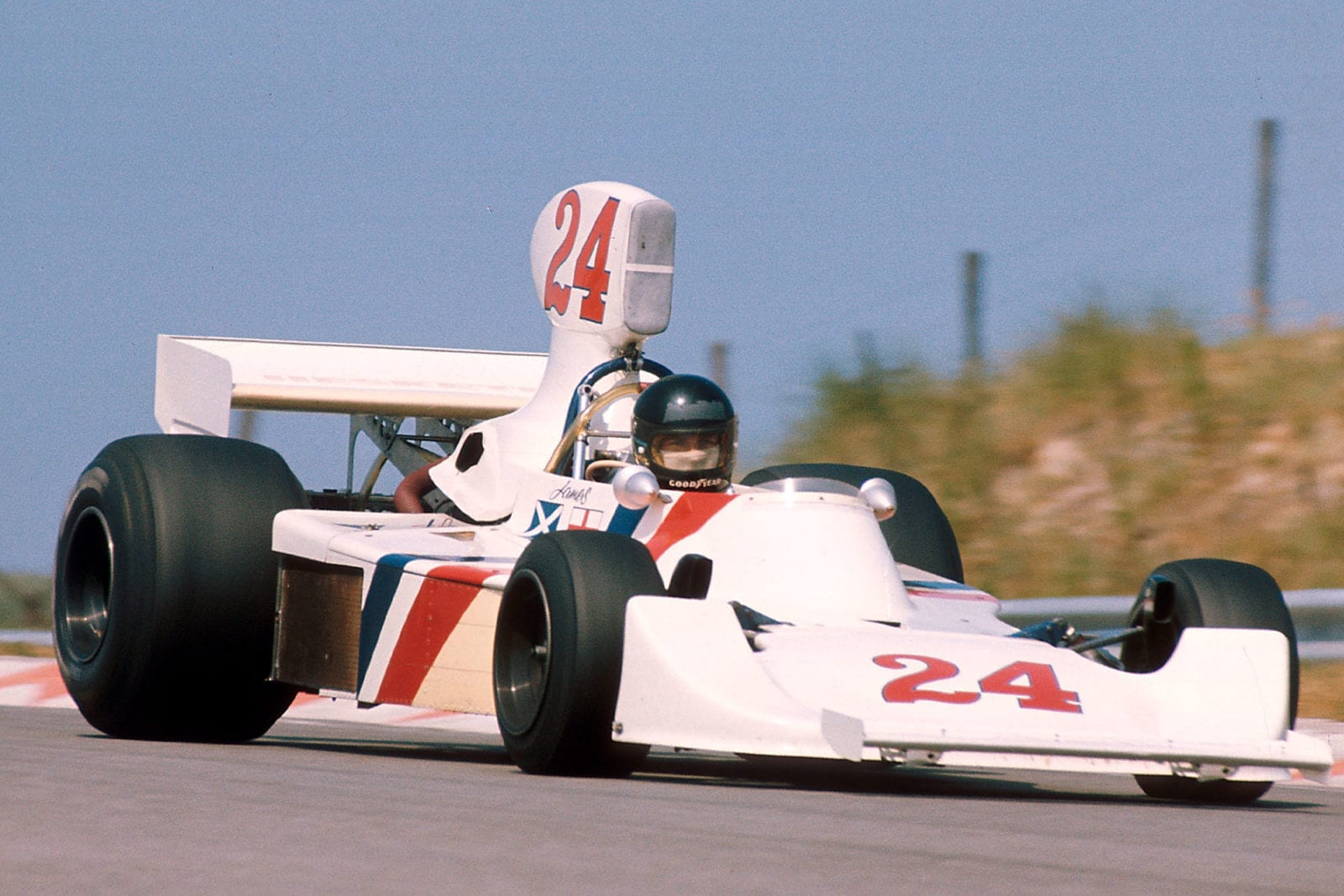

1975 Dutch Grand Prix race report

James Hunt claimed a debut win driving for the swashbuckling Hesketh team

Motorsport Images

An Englishman wins

Zandvoort, June 22nd

Everyone went to the seaside circuit in Holland resigned to the fact that the Dutch Grand Prix would be another Ferrari walk-over. Memories of the way Lauda and Regazzoni had dominated the 1974 race still lingered uncomfortably in the minds of the Cosworth V8 users, even though the massacre was avenged later in the season. The 1975 Ferraris, with their ever more powerful flat-12 cylinder engines and the new chassis with the transverse-shaft gearbox ahead of the rear axle centre-line, has been a resounding success and has been dominating the Grand Prix scene. Whether the Cosworth V8 engine has been powering Tyrrell, Brabham, Shadow, Lotus, March, McLaren or Hesketh running gear, the answer has invariably been that Lauda and the Ferrari have been the combination to beat, with Regazzoni often being a strong supporter of the Maranello cause.

Even before practice began at Zandvoort the tone was “who will be the quickest of the Cosworth-powered cars,” and the first practice did nothing to allay this feeling. The Ferraris were using long thin tail-pipes on their exhausts instead of the more usual megaphone ends and the engines were set for a wide power range to assist acceleration from the too slow, but important hairpin bends on the Dutch circuit. With a strong headwind blowing along the straight and Goodycars supplying everyone with “standard” tyres, there being no “super-sticky” ones for the chosen few, it was not anticipated that the all-time fastest lap of 1 min 18.31 secs set by Lauda in practice last year would be approached, even by the Austrian himself. The race lap-record stands to Peterson (Lotus) at 1 min 20.31 secs set up in 1973 and last year the fastest race lap was only 1 min 21.44 secs by the same driver and car. These sort of times give an average speed of around 116 m.p.h. and apart from the Panorama ess-bend, most of the back leg of the circuit is flat-out in fifth gear for the ace drivers. 1 min 20 secs was going to be a good lap time to aim for, while 1 min 21 secs or longer was not going to be very impressive or of much use for a good grid position.

The expected Ferrari domination materialized with Lauda and Regazzoni recording virtually equal times, the Swiss being fastest by a mere hundredth of a second, with 1 min 20.57 secs. Among the opposition was a single ray of hope in James Hunt, with the Hesketh 308/2, who just cracked 1 min 21 secs, by three-hundredths of a second, but everyone else was in the comparatively unimpressive category, while a few were down-right slow by ace-Grand Prix standards, but nevertheless very fast by normal standards. While all the leading teams were unchanged as regards drivers and cars, there had been some re-shuffling among the lower orders. The Harry Stiller-sponsored Hesketh 308/1 activity had ceased, so Graham Hill snapped up Alan Jones for the number two spot in his Embassy-sponsored team, alongside Tony Brise. “I had to have young Jones,” said Hill, “I used to race against his dad in the Tasman series.” Ian Scheckter was having another go with one of Frank Williams’ cars, and Jacques Laffite was back in the team. The Hesketh hire-car 308/3, driven in Sweden by Torsten Palm was back as Hunt’s Spare, all white and pure once more, and Wilson Fittipaldi’s little Brazilian team were pleased to have got a new car completed, their third altogether, this one having neater tubular front wishbones. Gijs van Lennep was driving Morris Nunn’s Ensign in place of Wunderink, who was still on the sick list, and there was a brand-new Ensign in the paddock, but it was not due to be run just yet. The Vels Parnelli team were missing once again, Andretti having a more important race to contest in the U.S.A., and a newcomer on the scene was Hiroshi Fushida with the blue and white Maki from Japan, though it looked as though it had been built in England, with its Cosworth V8 engine, Hewland transmission and Melmag wheels.

Qualifying

Championship leader Niki Lauda qualified his Ferrari 1st

Motorsport Images

The first practice session had been from 10 a.m. until 11.30 a.m. under cloudless skies, and after lunch the glorious weather and practice continued. From 1 p.m. to 2 p.m. the lappery continued and while Regazzoni was not so fast Lauda went much faster, down to 1 min 20.34 secs. However, two more drivers joined Hunt in the elite class, these being Scheckter with Tyrrell 007/2 and Reutemann with Brabham BT44B/1. All three were greatly encouraged by being faster than Regazzoni on the afternoon times, but they were still slower than his morning time, so the end of the first day saw the two Ferraris on the front row of the grid. The Maki did not appear after lunch as the oil pressure disappeared from the Cosworth engine and the small team had no spare engine. That the Zandvoort circuit is not a very difficult one for a skilled driver of a Formula One car was shown by ten drivers recording times within the span of three-quarters of a second. To most people one whole second of time is difficult to visualize, let alone three-quarters, and in that space were Emerson Fittipaldi, Jarier, Brise, Brambilla, Laffite, Watson, Mass, Pryce, Pace and Depailler; a situation that brought forth some discussion on the validity of the existing method of timing practice laps.

Saturday was another hot and hazy day, but the headwind on the main straight was stronger which prevented the fast ones going any faster, but allowed a few more to get a bit closer and join the under 1 min 21 sec group. World champion Fittipaldi just scraped into this group, as did Tony Brise with the Hill car. Apart from the two Ferraris which were recording “ace” times at every session, no-one else got below the 1 min 21 secs barrier. Although the two Ferraris were dominating the scene it was not without a certain amount of untoward excitement. Lauda had the rear suspension come adrift on his car, and later had the nose section and front aerofoil mounting collapse, while Regazzoni had his engine go off song, requiring a complete change at the end of Friday, and on Saturday he had a misunderstanding when passing Scheckter, who was going relatively slowly, and the Ferrari clobbered the front of the Tyrrell, both cars being slightly damaged. There were a certain amount of excited shouting in Italian and Afrikaans, but it soon died down.

Conditions did not alter for the final hour of practice and just to convince everyone, Lauda improved his time to 1 min 20.29 secs, consolidating himself yet again on pole position. Fittipaldi appeared to have the measure of things and once more broke the 1 min 21 sec barrier, but there were no other “ace” times, though one or two drivers improved their lot, moving up from a lowly place on the grid to a not so lowly place. Competition among the mid-field runners was very intense, the second place of decimals on a lap time pushing a driver back another row on the grid. Lauda and Regazzoni had complete command of the front row of the grid, with Hunt and Scheckter behind them, their times almost being equal. Then came Reutemann, his best time being made in the spare Brabham, alongside E. Fittipaldi, with Brise the only other driver in the “ace” category. From Jochen Mass in eighth place with the second of the works McLarens, to Peterson in sixteenth place in Lotus 72/R9, there was less than half a second difference, and in this tiny gap were Pace, Jarier, Brambilla, Pryce, Depailler, Watson and Laffite, so that even if the two Ferraris were out on their own, there was going to be a very close pair of Cosworth races, for only a quarter of a second separated the five Cosworth-powered cars in the “ace” class. Rather dejectedly at the back was Ickx, who looked as if he had retired from Grand Prix driving, but had omitted to tell anyone.

Race

Lauda leads the field through the spray

Motorsport Images

Sunday started off another bright and sunny day, but it did not last, for grey clouds came front the east, bringing rain and by mid-day everything was covered up and the whole paddock sheltered from the heavy rain, only the poor unfortunate spectators being unable to do anything about the conditions. Dutch laws do not allow noise-making on Sunday mornings so there was no untimed test-session as is usual at other races, but with the weather looking settled at “wet”, the organisers agreed to do a short test-session before the start of the Grand Prix so that everyone could try out their cars on wet-weather Goodyears and with suspension and aero-dynamic settings for slippery conditions. The race was due to start at 2.15 p.m., but after the test-session there was a reluctance to get on with the job as the rain had stopped and it looked as though conditions might improve to “dry”. It was more than 30 minutes after the scheduled starting time that cars began to leave the pits on the warm-up lap round to the dummy-grid, by which time many teams had opted for “dry” conditions. However, while the cars were on their way to the start the rain came down again, and there was a rush to change tyres and adjustments to full “wet”. Eventually the 24 cars were ready to go and the two Ferraris led them up to the starting grid, ready for what looked like 75 laps of wet misery.

The flag fell and the two Ferraris hung momentarily with spinning rear wheels, while Scheckter made a superb start and moved up alongside them, his left hand wheels on the grass verge. Lauda found grip and accelerated away, but Regazzont was slow and Scheckter got his Tyrrell into second place as spray enveloped the whole scene. In the confusion Depailler clouted Brambilla’s March and as the field rounded the Tarzan 180-degree corner, the orange March came to rest with a broken rear suspension and the Tyrrell had a deflating right front tyre. While Lauda led Scheckter, Regazzoni, Hunt, Mass, Pryce, Fittipaldi, Reutemann, Pace and Jarier on the opening lap, Brambilla reversed his damaged March up the pit lane to retire, while Depailler limped round to the pits for a new front wheel. With so much spray coming off the tyres no-one got too close to the car in front, and Lauda looked confident in the lead. Fittipaldi dropped back behind the two Brabhams and after Jarier in tenth place a gap had opened up before Peterson came along leading Brise, Donohue, Jones, Laffite, Watson, Ian Scheckter, Ickx, van Lennep and Evans. Behind the BRM and dropping back, were Wilson Fittipaldi and Lombardi, while Depailler was last but making up ground.

Barely had the race order sorted itself out than the rain stopped, and equally quickly the track dried out, especially on the “racing-line,” the passing cars assisting with the drying process. At the end of lap 7 Hunt had made his decision and peeled off from his fourth place in the high-speed procession and headed at speed down the empty pit lane to the Hesketh pit where the mechanics were waiting for him. In less than half a minute he was on his way again with four new wheels, and “dry slick” tyres, joining the race in nineteenth position. Mass had stopped at the end of lap 7 as well, and rejoined the race just behind the Hesketh, while at the end of the lap 8 Reutemann stopped for a tyre change. On the next lap Emerson Fittipaldi stopped for “dry” tyres and with the track drying visibly it was obvious that the rest would be in soon. Lauda was still in the lead, driving off-line on the wet parts of the track to keep his knobbly tyres cool, and trying to build up as much a lead as possible before making his stop. At the end of ten laps Jarier, Watson and Wilson Fittipaldi stopped for “dry” tyres and the race situation was Lauda, Scheckter and Regazzoni well out in front, then a gap to Pryce, another gap to Pace, a gap caused by Jarier peeling off, then Peterson, Brise, Donohue, another gap, then Jones, Evans, the elder Scheckter, van Lennep, and then a very long gap from which Watson had peeled off. On “dry” tyres now came Emerson Fittipaldi who had rejoined the race just in front of Hunt, then Reutemann and Mass, the gap from which Wilson had peeled off and then Depailler. Already Lombardi had been lapped by the leading Ferrari.

Jochen Mass (foreground) and Tom Pryce attempt to get to grips with the slippery conditions.

Motorsport Images

Naturally this situation did not last long, for pit-stops for “dry” tyres were happening thick and fast and at the end of lap 11 Pace, Peterson, Donohue, Laffite and Evans all stopped and the pit lane was a busy place. As Peterson set off he collected the Ferrari team co-ordinator, who was prancing about in the pit-lane, upending him and breaking one of his legs. The Lotus was undamaged and Peterson got on with his racing. At the end of lap 12 Scheckter, Pryce and Brise stopped and the situation was Lauda still leading, with Regazzoni now second, Jones third, but it was all still relative, though what really mattered was that of those on “dry” tyres the order was Hunt, Jarier, Fittipaldi, Reutemann, Mass, Peterson. Next time round it was Lauda who was heading for the pits, leaving Regazzoni in the lead, and Jones was also in the pits. After Regazzoni had gone by there was a long gap and then came Hunt, Jarier, Fittipaldi, Pryce, Scheckter and the rest, the crucial point now being that Hunt had a clear road ahead of him. Lauda rejoined the race after Hunt had gone by and just ahead of Jarier, but during the next two laps while he was acclimatizing himself to the new conditions Lauda was passed by Jarier in the Shadow. As Regazzoni had gone into the pits for tyres one lap after Lauda, the situation was now all sorted out with Hunt out in the lead with no traffic in front of him, Jarier second, Lauda third, Fittipaldi fourth, Scheckter fifth, Regazzoni back in the race in sixth place, followed by Pryce, Reutemann, Mass and Peterson. Apart from Pace, whose stop had taken too long because a wheel baulked at going on the locating pegs, everyone had made good stops, Ferrari, Hesketh and McLaren being particularly fast and it was good to see the progress made since the notorious situation in the Spanish GP two years ago. The race was now on its seventeenth lap, with conditions now very dry and all things equal to everyone, apart from minor differences in wing angles and roll-bar settings, depending on how things had been adjusted before the start.

Profiting from his early stop, which had meant an unobstructed run in and out of the pit lane and a clear road ahead of him as soon as he had settled down to the dry conditions, Hunt now had a sizeable lead, but stop-watches soon showed that Lauda was gaining on the Hesketh. As Jarier was between the Hesketh and the Ferrari it meant that the Shadow was being urged along on two counts, one to gain on Hunt, the other to stay ahead of Lauda. The new race was now on in earnest and a most interesting situation it was, for the Ferrari did not appear to have any superiority over the Cosworth-powered cars, it being no faster down the straight and Lauda was driving as hard as he knew how. Hunt was driving for his very life, knowing that his pursuers were closing on him yard by yard, tenth of a second by tenth of a second, but he was determined to keep going as hard as he could and above all not to make any mistakes. The three contenders for the lead were now well ahead of the rest of the runners, with Scheckter in fourth place and Fittipaldi in fifth place, but in trouble with a gearbox that would not select fifth gear. He was followed by Regazzoni, Pryce and Reutemann, while Mass had dropped back due to a throttle control that was playing up. In the excitement of pit stops and the new pattern no-one seemed to notice that Ickx never got as far as “dry” tyres, his Cosworth engine blowing up out on the back of the circuit. With the new situation at the front now so interesting, the happenings among the tail-enders almost passed unnoticed, though Evans was seen to retire the BRM with the final-drive unit breaking up, spoiling his excellent record of steady finishes in the sad and lonely car from Bourne.

Hunt soaks up the pressure

Motorsport Images

At 30 laps Hunt had an eight-second lead from his pursuers, but Lauda had the Shadow in his sights and Jarier was beginning to look in his mirrors as much as he was looking forwards. Fraction by fraction Hunt’s lead was being whittled away, but he had no intention of giving up, and when it was down to five seconds Lauda was ready to take second place from Jarier, but the Frenchman had other ideas. The only way to pass an equal car at Zandvoort is to out-brake it past the pits into the long 180-degree Tarzan bend, diving through on the inside and forcing your rival to run wide up the banked turn. As they started lap 39 Lauda did exactly this, except that Jarier was not accepting the manoeuvre and stuck to his line, so that Lauda had to do some desperate braking and scrabbling about to avoid being run into. Twice more Lauda tried it on and twice more Jarier was unimpressed and the order was unchanged. This little fracas took the pressure off Hunt for a brief moment, and for a couple of laps Lauda sat close behind Jarier wondering what to do about the situation. As they came down the straight to complete lap 43 the Ferrari was that much closer to the Shadow and while still on full song Lauda pulled out of the Shadow’s slipstream and side-by-side they went past the pits. This time Jarier had no option but to run wide and Lauda was by, but it was a tense moment, and Grand Prix racing at its best. Now Lauda could really get to work and catch the fleeing Hunt. Almost unnoticed Emerson Fittipaldi had retired when his Cosworth engine blew up and Watson had succumbed to vibrations that were shaking the back of his Surtees to bits. For one lap Jarier followed Lauda, holding third place, and then made a spectacular disappearance from the race when a rear tyre literally exploded in a shower of bits of rubber. This was on a fast right-hand bend and the Shadow driver was very lucky not to be hit by other cars as he spun out of control. There was now only four and a half seconds separating Hunt and Lauda and still a long way to go. In a secure third place was Scheckter, followed by Regazzoni and after a gap Reutemann was fending off a spirited attack from Peterson; then came Pryce, unhappy about the feel of his brakes and the handling of the car in general, and he was followed by Mass still struggling against the odds with his unpredictable throttle response. The only other car on the same lap as the leaders was the Brabham of Carlos Pace, unable to make up for his long pit-stop. Donohue was leading the also-rans but few people had eyes for anyone but the two cars at the front of the race.

Slowly but surely Lauda whittled away the gap until the Hesketh pit-stopped giving Hunt the time gap for the Ferrari was close enough to be seen by the leader, but still the English driver did not give in and began to look for any help that might enable him to retain the lead a little longer. They were now about to lap the faster runners and Hunt planned his every move with care and forethought. On lap 57 the Ferrari was right behind the Hesketh and next time round it looked as though Lauda might make his bid to outbrake Hunt, but at that moment they lapped Torn Pryce and Hunt made the most of the situation as Lauda was put off his stroke. Two laps later they lapped Mass and once more Lauda was put off balance, and for ten laps he had to work away at retrieving lost ground. Now they were passing some of the slower cars and Hunt took every opportunity afforded him, nipping past one before the “chicane” on the back of the circuit, in a desperate scrabble so that Lauda got hung up, waiting to pass another just before the flat-out sweep onto the long straight so that Lauda’s run-through onto the straight was hindered. So it went on, with Hunt doing a superb job of fending off the Ferrari, using every trick in the book. At times Lauda had the nose of his car right under the tail of the Hesketh, but never at a point on the circuit where there was any hope of passing, and Hunt was making sure it stayed that way.

With two laps to go they had got past all the slow traffic, as well as lapping the faster cars and entirely unnoticed Scheckter disappeared from third place when his Cosworth engine blew up and equally unnoticed Peterson retired from fourth place with no petrol getting to his injectors. All this left Regazzoni a distant third, Reutemann fourth, a lap down, followed by Pace. But no-one was very interested for it was now or never if Lauda was going to win his fourth Grand Prix in a row. Hunt had other ideas and having fought for his life this far he had no intention of throwing it all away by a last-minute false move. Going into the last lap Lauda was close, but not close enough to try a passing manoeuvre and he had no choice but to follow the Hesketh for the final lap, having been following it at varied intervals since lap 43.

A proud Hunt stands on the podium after winning

Motorsport Images

A joyous James Hunt swept past the chequered flag to bring the first major victory to the Hesketh team and his own first Grand Prix win, and what a magnificent win it had been. It was Grand Prix racing at its very best and the best possible victory for an English driver, the first since Monza 1971. D.S.J.

DUTCH GRAND PRIX – Formula One – 73 laps – Zandvoort – 4.226 kilometres per lap – 316.95 kilometres – Wet and dry

Zandvoort Azides

Dr. Harvey Postlethwaite, the designer of the Hesketh was suffering from Dr. Sodt’s law. He went home on Saturday night to carry on working on a new Hesketh car.

Ferrari may have been beaten, but to finish second and third is something a lot of teams would like to do.

Jochen Mass ended up in the catch fences when his Mc-Laren decided to respond to the throttle just when he did not want it to.

Tony Brise lost a lot of time on the drying track before making his pit stop and though he was lapping as fast as the leaders afterwards, he could not make much headway against a whole lap handicap.