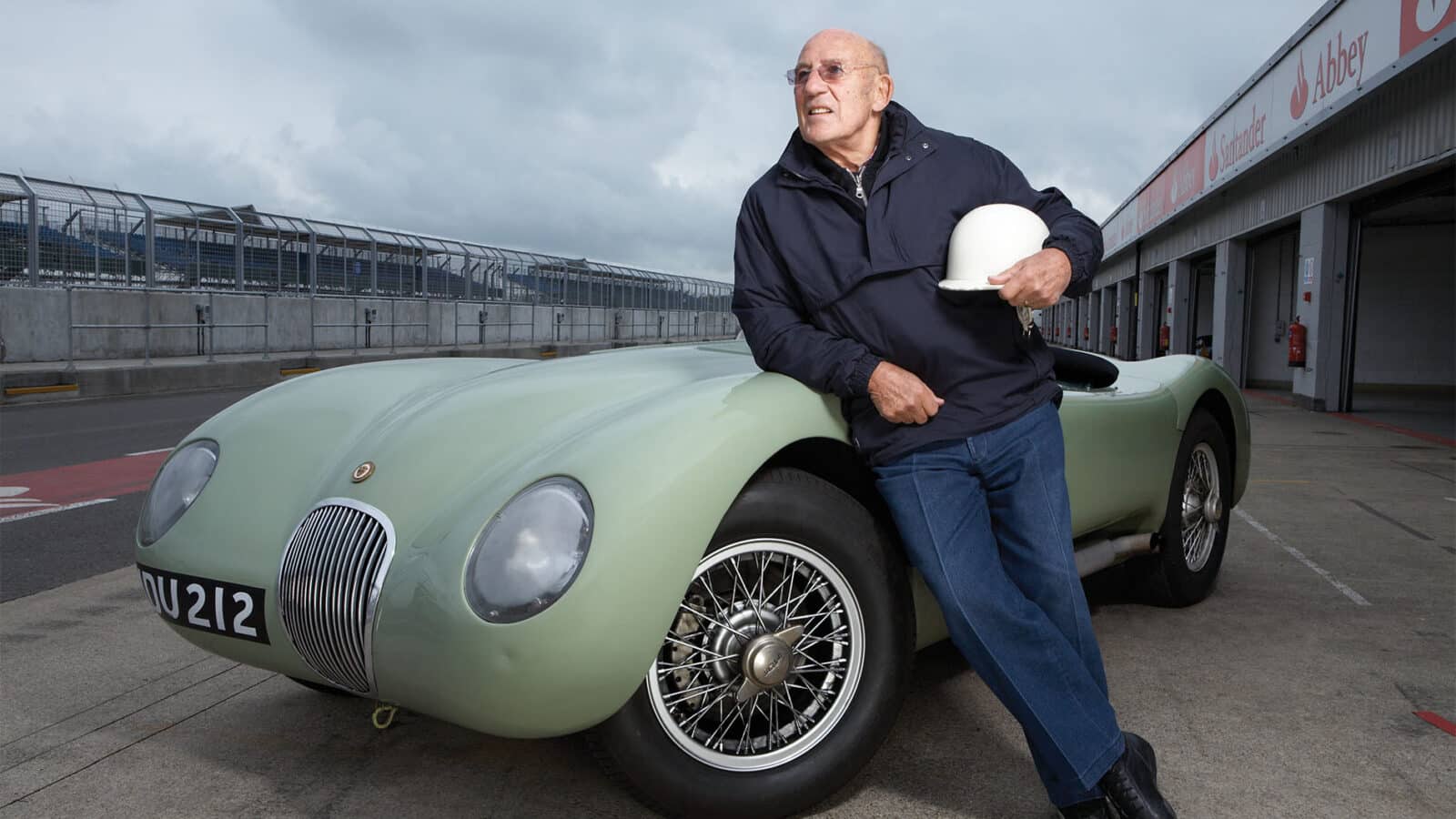

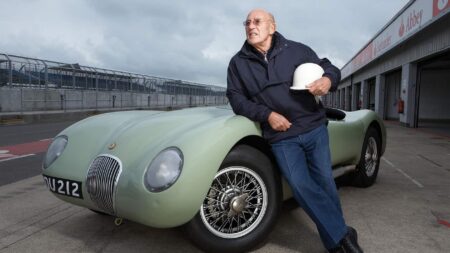

There are other reasons why Stirling might struggle to recall the events of June 29, 1952: for a start it was a far from riveting race on a far from riveting slipstreaming circuit that suited the C-type’s superior aerodynamics very well. “I remember it was extremely hot and having a bit of a dice with a Gordini which I think then broke but not much after that.” No wonder; after Manzon’s Gordini bust a stub axle, Stirling drove unchallenged to the flag winning at an average of 98.2mph, but was so exhausted by the sweltering weather and the heat soak of the straight-six motor that he had to be helped from the car and propped up for the National Anthem by Jaguar team manager Lofty England.

But even if the race did not lend itself to long-term recall, Moss was one of a tiny number of people who absolutely appreciated its significance at the time. Of all the drivers contracted to Jaguar at the start of the disc brake’s development it was Moss who had the ability to see through its many manifest problems and identify its true potential. In Paul Skilleter’s masterly biography of Norman Dewis, there are lurid tales of centre pedals going to the floor at three- figure speeds during testing, for which the only approved protocol was to change down, turn into the fast approaching corner and then spin the car, all of which appeared to leave Dewis entirely unfazed.

“I’d done a lot of work with Norman and Dunlops trying to fix the disc brakes and while there were some terrible problems, we could see that if they could be ironed out the advantage they’d give us would be simply incredible. Back then if you treated conventional drum brakes as we now do discs, you’d be out of brakes in a couple of laps, maybe less. If your brakes were going to survive they had to be managed throughout the race, meaning you could never use them as you wanted. Even then we could see that discs offered the possibility of being able to brake as hard as you could for every corner on every lap for the duration of the race.”

Fuel cap tells of car’s proud history

Marc Wright

Indeed it is Stirling who claims the credit for persuading William Lyons and Bill Heynes to enter the Reims race and to annex the Wisdom C-type for those purposes.

Why Reims? “It’s simple, really. The brakes not only suited the C, they also gave the brakes time and air to cool off.”

Even so, Stirling had fast developed the habit of giving the brakes a quick precautionary stab just before they were really needed to make sure the pads were properly relocated, and while the brakes appear to have worked precisely as they should have during the race, when the car came to be driven away at the end, the few minutes standing still in the sunshine was all it took to overheat the fluid and sink the pedal to the floor once more.

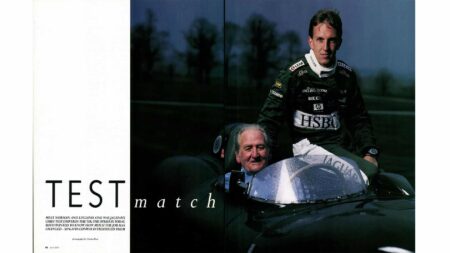

There will be no such problems today. Silverstone is awash, the modern fluid has a boiling point far above that available in 1952 and in this weather and that car no-one, not even Stirling Moss, is going to be flat out, least of all with the world’s worst passenger sitting next to him. Which is me.

He sits in the way he always has, upright and straight-armed. It may not perhaps be the most orthopaedically correct driving position, but it is his trademark and with his record it’s not something I’m going to question. He turns the small key and despite the fob completely obscuring the starter button below, his finger finds it at once. He’s been here before.

“Quiet, isn’t it?” he says with considerable surprise. Those stubby side exhausts look mighty loud but the standard specification of the engine means conversation is still eminently possible above the burble of the just awakened twin-cam straight six.

The gearbox is slow, awkward and not really suited to the free-revving nature of the engine, but so wide is its torque spread that here on Silverstone’s ultra-quick Historic Grand Prix circuit you’d only use the top two of its four ratios. We’re already into third as the pitlane merges into the track, the engine is singing its inimitable tune and Moss is ready to go to work.