It wasn’t a success. “Couldn’t get out of its own way in 1983,” recalls the ever cheerful Needell today. “It really was a disaster – as the speed rose it just ran out of power.”

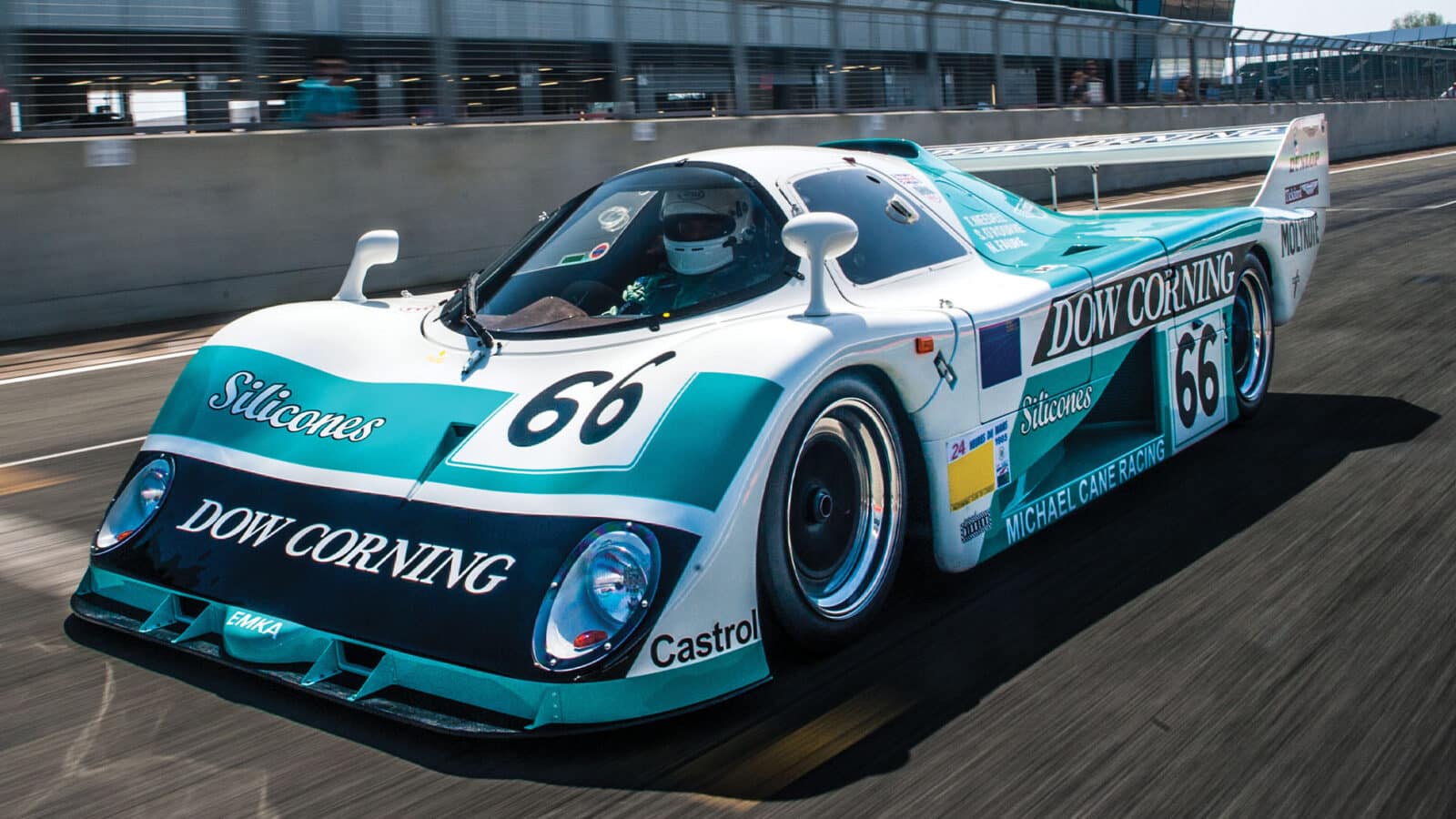

The car made its debut at the 1983 Silverstone 1000Kms, boasting the red bodywork of its Virgin sponsor and carrying a C83/1 chassis plate. In Tiff’s hands during qualifying it proved only slightly slower than the Nimrod that had made its debut in the same race the year before and gone on to record a highly creditable seventh place finish at Le Mans. The race itself proved somewhat trickier, perhaps inevitably for such a new car. Tiff drove with O’Rourke and Jeff Allam but electrical issues slowed the car before wheel-bearing failure brought its run to a halt after 165 laps.

At Le Mans the car’s paucity of power was shown in rather starker light, especially against Porsches running qualifying boost in practice. With Nick Faure replacing Allam in the driver line-up, it managed a 3min 42sec lap, 26sec off the pole time, 7sec behind the Nimrod using the same engine and good enough only for 25th place, a scant half second quicker than the fastest car in the C2 category. “The car got up to 180mph and just stopped,” Faure remembers today. “That would be pretty inconvenient anywhere, but at Le Mans without the chicanes? It was completely hopeless. Porsches were pinging past us going 50mph faster, and more…”

The race was a grind, the car suffering a litany of faults and failures and circulating slowly even when functioning properly. But it got across the line, 17th of 20 finishers and last but one of the Group C contenders, at least earning the Motor Trophy for the first British car home. And that, it seemed, was that. The EMKA didn’t race again in 1983 nor the following year. But its moment in the sunlight was still to come.

The EMKA-Aston Martin’s rebirth

Booming Tickford V8 delivers plenty of punch

Jayson Fong

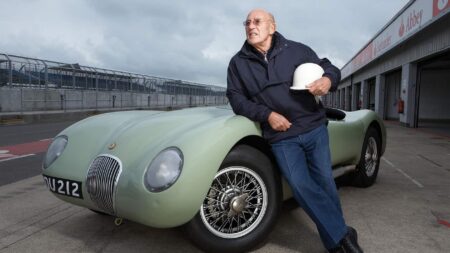

A very different EMKA-Aston Martin appeared at the start of the 1985 season. It was developed from the ’83 car but was so heavily evolved it was given a new chassis number, the C84/1 it wears today. “You’ve got to mention Richard Owen,” implores Tiff.

“He was the man who did all the work. He transformed the car.” And so he did. Owen is a race car designer and engineer who had been responsible for the Shrike and Aquila racers. His career involved stints at BRM, TWR and Williams and he was drafted in by Cane to see what could be done to make the car quicker.

“The brief was to find another 20mph top speed,” says Owen from his Towcester office where he remains as busy as ever. “I had a look and saw pretty quickly that the problem was the intake into the engine: it was simply being starved of air. So I did a new rear wing for it, and new suspension for some reason or other, but the big difference was redesigning the air intake in the tail.” Owen does not recall removing the ground effect tunnels, but there is no sign of them today.

Whatever he did, it worked. This time in Le Mans qualifying Tiff went nine seconds faster than the car had gone in 1983, good enough for 13th, ahead of three Group C Porsches and, gratifyingly, both of Bob Tullius’s IMSA Jaguar XJR-5s. It was the fastest normally aspirated car on the grid.

High tail exposes EMKA’s lack of ground effect – but that makes it great fun to drive

Jayson Fong

Needell started the race. “I had a riot. All the Porsches were being quite conservative with their fuel so I just weaved my way past. Having been so slow in 1983, the thing now just flew down the straight.”

Owen had found the required 20mph and quite a lot more. By the time of the first fuel stops and entirely on merit, the EMKA lay third, an almost impossible turnaround in fortune from its previous visit to France.

“I could see the Joest and Canon cars up ahead and had no trouble staying with them,” says Tiff.