Was Stirling Moss’s 1955 British Grand Prix win a fix?

It’s 70 years since Stirling Moss’s first Formula 1 victory. But was the win handed to a British driver on home soil? Mike Doodson re-opens the case of a motor sport mystery – and finds the answer

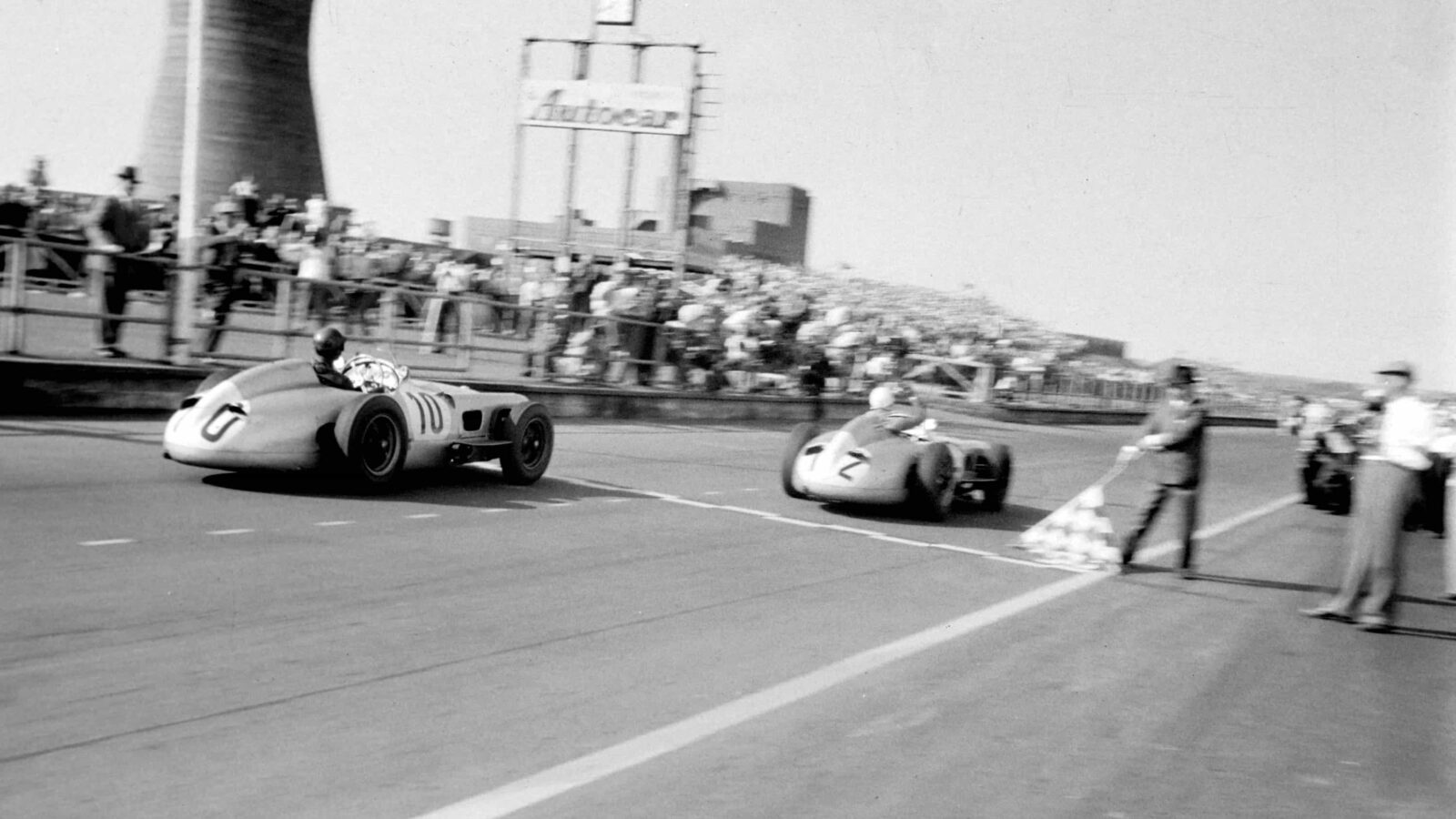

Stirling Moss leads a Mercedes 1-2-3-4 at Aintree, with Juan Manuel Fangio just 0.2sec behind. A brilliant win for the ‘Boy’ or a gift from the Old Man?

Getty Images

This was a race which has been the subject of debate and argument almost since the flag fell on it. Not that it had been a particularly complex duel on that hot, dry summer afternoon, apart from the one vital question that needles to this day: did Stirling Moss win it or was it gifted to him by Juan Manuel Fangio, his two-time Formula 1 world champion team-mate at Mercedes?

Fangio and Moss, brothers in arms before the race

The W196s of, from left, Karl Kling, Piero Taruffi, Moss and Fangi

While that race of 70 years ago and its 0.2sec winning margin have become a rabbit-hole down which this magazine and a galaxy of its writers have cheerfully burrowed over the decades, it was not something that greatly bothered the media back in 1955. The explanation for that, I suggest, is that the regular newspaper hacks regarded that year’s Formula 1 drivers’ championship as all but settled, with Fangio arriving at Aintree with a 14-point advantage over Moss (27 points to 13) and only two rounds left to run.

“The race has become a rabbit-hole down which a galaxy of writers have cheerfully burrowed”

Lest we forget, the F1 calendar of 1955 had lost four events (in Germany, Switzerland, France and Spain), all cancelled by worried promoters in the wake of the Le Mans disaster that had cost dozens of spectator lives in June. Britain’s mid-July event would be the fifth round, with the final contest not now due to take place until Monza, in September. Bearing in mind that Fangio, 44 years old at the time, had won three of the four pre-Aintree events, and that Moss, still a relative youngster at 25, had yet to break his grand prix duck. The Argentine veteran was all but guaranteed his third title.

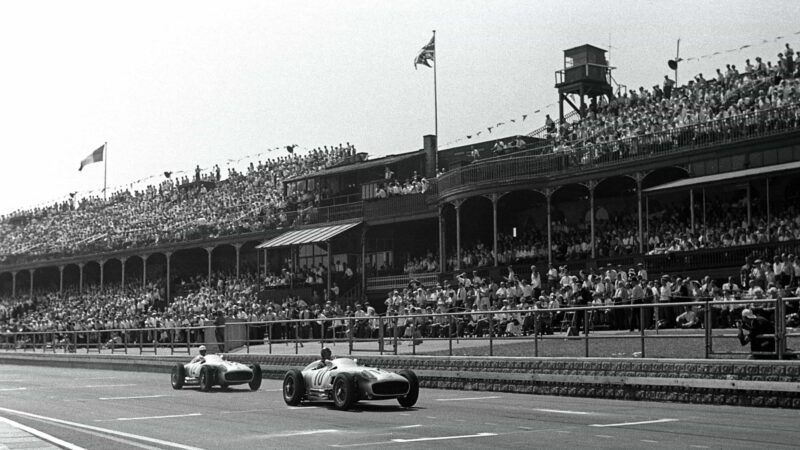

In 1955 the all-new Aintree circuit hosted the British Grand Prix for the first time, with as many as 150,000 in attendance

Getty Images

The FIA’s points allocation then was 8-6-4-3-2, with a bonus point for fastest lap. Although this meant that there was a mathematical possibility of Moss surpassing Fangio, the Englishman made no secret of his hitherto worshipful attitude towards his team-mate. Fortunately for us students of track history, the ‘Boy’ was about to break the mould by actually tackling his hero and taking the race to him for the first time. Or did he?

What is clear about that Saturday afternoon at Aintree is that there was some place-swapping between Mercedes’ two aces, at least in the early stages of the 90-lap, 270-mile event. Moss had narrowly beaten Fangio to pole position for the first time that year, by 0.2sec, only to be relegated by him in the first-corner mêlée.

Within three laps Moss had ducked back into the lead, only to be re-passed on lap 18. But as Richard Williams helpfully remarked in a piece about Mercedes’ 1955 season in The Observer in 2021, “an adroit piece of work in lapping a backmarker under braking for a corner [on lap 26], forcing Fangio to fall back, allowed Moss to build a cushion; this was a trick he had learned from Luigi Villoresi at Monza a few years earlier, while trying to follow the Italian’s Ferrari in his HWM.”

Was Mercedes racing chief Alfred Neubauer – in the suit – giving the British public a home hero victory? Moss said not…Although Williams was not present at the race, our own Denis Jenkinson was able to take up the story. “By Lap 40 Moss had increased his lead to 9sec, due to nipping through some slower traffic while Fangio had to wait.”

However, another Motor Sport regular, Michael Tee, has a quaint alternative explanation for the suddenly increased gap between the battling Benzes, one which had nothing to do with Villoresi’s ‘trick’.

Tee, photographing the race at the far side of the circuit, told our own Simon Taylor in 2014 that Fangio had lost the time in a grassy off-road diversion close to where he was standing. He claims that encountering the great champion post-race, he was given a reproachful finger-wagging, which he interpreted as a rebuke for having moved his position, thereby depriving the unfortunate ace of using him as a braking-point marker.

“The ‘Boy’ was about to break the mould by tackling his hero and taking the race to him”

As the race wore on, Mercedes team chief Alfred Neubauer put out signals requiring his drivers (there were four of the silver cars in the race – Moss, Fangio, Karl Kling and Piero Taruffi) to slow down. According to Jenks, in a book published to celebrate Hugh Hudson’s glorious biographical Fangio: Una Vita a 300 All’ora film in 1980, Neubauer had decided that the race should be Moss’s. In fact, Fangio had previously agreed to a similar scheme in 1954, when he yielded the lead to team-mate Kling in a ‘demonstration’ race at the AVUS circuit.

Here we acknowledge the contribution to the story of our colleague Nigel Roebuck, who had the advantage of having been present at Aintree for the ’55 British GP, albeit only nine years old at the time. Later, as a seasoned F1 writer, he had an opportunity to quiz both Moss and Fangio: those conversations appeared in these pages in 2003. “It is entirely possible, as Moss [now] says, that Neubauer whispered in Fangio’s ear before the start, that Stirling was permitted to win,” Roebuck recounted. “But he seemed to have had an edge throughout that particular weekend, and had beaten Fangio to pole position. In the race, his fastest lap was almost 2sec faster.”

By the 1955 British GP, Fangio was on course for his third drivers’ world title

Moss remained nonplussed. “Don’t ask me if he let me win that day, because in all honesty I don’t know,” he told Roebuck, “and it was something we never discussed subsequently. I can tell you that there were no prearranged tactics between us, no team orders from Neubauer.

“Perhaps it was suggested to Fangio that he should let me win, because it was the British Grand Prix. It’s quite possible. But he wasn’t the kind of guy who would ever have let me know it, unlike some drivers of the recent past. He had too much class for that.”

So, Roebuck mused, had the great Juan Manuel privately decided to allow his young team-mate to win his first GP victory that afternoon? Could there even have been a technical quirk which had disadvantaged him? On the one occasion when Roebuck was able to interview Fangio, he did not hesitate to put that question to him. The great man’s response, he records, was typically enigmatic: “I don’t think I could have won, even if I’d wanted to. Stirling was really pushing that day, and his car had a higher final drive than mine. It was quicker.”

Moss was fired up for the British GP, taking pole, fastest lap and a narrow victory. He’d go on to win another 15 world championship races

Getty Images

Jenkinson’s account in his 1973 book Fangio gives weight to the assumption that while Neubauer had instructed Fangio to yield to his British team-mate once the race was underway, the younger man had been entirely left out of the plot. Indeed, as he told Roebuck, Moss had neither received any instructions from Neubauer nor come to any sort of an arrangement with Fangio. As far as he was concerned, the 1955 British Grand Prix was a straight fight. Nor, intriguingly, did he ever acknowledge that he had the slight edge under acceleration that he would have had with the higher axle ratio that Fangio so punctiliously mentioned to Roebuck.

“I don’t think I could have won, even if I’d wanted to. Stirling was really pushing that day”

As a result of Fangio’s later-race surge, the two Silver Arrows were nose-to-tail as they approached the finishing line. Moss appeared to lift off, enough to allow Fangio to draw almost level, only to floor his Mercedes and assure himself of victory. “I backed off on the last lap,” Moss told Roebuck, “because I wasn’t sure of what we were supposed to do — but when the Old Man was still behind me at the final corner, I can tell you I gave it everything on the run up to the line!”

Thus the question lingers. Did Fangio gift the race to his team junior? By deliberately holding station behind him for the latter half of the race, we can surmise that it was his (or Neubauer’s) intention to present Moss with his first grand prix win, in his ‘home’ race at Aintree. But then there was Fangio’s catch-up flurry, seemingly in defiance of the boss’s signals, which put them nose-to-tail on the last lap. What was going through his mind?

With the race ended, the restless minds of motor sport writers began to question the result. Right: Aintree’s last British Grand Prix gets underway in 1962

Getty Images

Here, the final word on this decades-long mystery goes, deservedly, to Doug Nye, Motor Sport’s house historian, in the foreword that he asked Fangio to provide for the splendid 1987 book Stirling Moss: My Cars, My Career which was put together in collaboration with Nye. While written by Fangio in the calm of his long retirement, it reveals a deal brokered between the two men that may have made sense at the time, but which neither of them would respect.

Addressing himself directly to Stirling in the book, Fangio wrote: “Then there were the times when we raced each other from start to finish, until the ’55 Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, when you finally agreed with me that the battle between us should only last until we had gained a certain advantage over the competition. Then Neubauer had to show us the ‘Langsam’ pit signal [slow down] and whoever was in front stayed in front, and whoever was second stayed second.”

“Then there was Fangio’s catch-up flurry, seemingly in defiance of the boss’s signals”

Here is the proof that there was indeed an agreement between the two men not to engage in combat on track once the order was settled and they were signalled to cool down. It’s a great idea, of course, but one which will never sit comfortably with competitors whose overlying ethos is to win, come what may.

The deal made in Belgium in 1955 did not survive. At Aintree, there was no denying that both Fangio and Moss ultimately chose to disobey it.

If only we had known this at the time. It would have been a lesson to the cavalcade of team bosses who decreed, sometimes in written contract, that team orders might be put into operation. If greats like Fangio and Moss couldn’t keep their word, what chance that the likes of Villeneuve/Pironi, Prost/Senna, Piquet/Mansell, Vettel/Webber, Hamilton/Rosberg and their teams would have done the same?

The lesson? In Formula 1, any attempt to keep a good man down is ultimately doomed to fail. The craving to win will always defeat good intentions.