Confined to Paris, deprived even of a driving permit, he found some freedom to begin work on plans for a revolutionary road-going saloon car. Among many innovations were a rear engine, all-round independent suspension and three seats abreast with the driver located centrally, a mere 50 years before the McLaren F1… Simultaneously, he was being touted as a potential Minister for Sport, and planned an abortive Bugatti assault on Indianapolis with Raymond Sommer.

As has already been documented in these pages, Bugatti teammate ‘Williams’ had formed an SOE network in Paris. After his capture by the Gestapo a new group, CLERGYMAN, rose from the ashes, headed by Robert Benoist. At Benoist’s request, Wimille and his wife were recruited by Bugatti secretary Stella Tayssedre, and in the months leading up to the Normandy landings the group collected weapons and ammunition dropped by the RAF so as to arm the volunteers of the Forces Francaises de l’Interieur.

Hours after D-Day, Benoist was captured in Paris and the remainder of the group were ambushed at the farmhouse meeting-spot. At the first sign that something was amiss, Wimille grabbed Cric and made to dive through the ground-floor window. He fled under gunfire while the petrified Cric remained rooted to the spot. The entire group, save Jean-Pierre who was by now hiding in a stream, were rounded up. Several — Benoist included — would die at the hands of the Nazis.

Wimille linked up with a column of Americans making their way to Paris. Cric, meanwhile, was imprisoned at Fresnes before being put on a train for Germany and a fate at best uncertain. Just out of Paris she escaped, and ultimately made her way to the house of friends, where she and her husband were reunited.

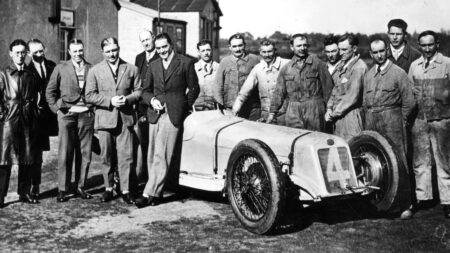

Wimille won the first postwar race, in the Bois de Boulogne in 1945

Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Wimille was back in the Armee de l’Air when the war ended, and was only granted permission for leave at the last minute so that he might take part in the first post-war Grand Prix. This was in Paris’s Bois de Boulogne on 9 September 1945. His late arrival meant his starting from the back of the grid, but the 4.7-litre Bugatti monoplace (the old Type 59/50B) was easily the most powerful car in the field, and he won convincingly.

The only works team to intimate a return to racing in 1946 was Alfa Corse, and Wimille was keen to capitalise on his brief pre-war flirtation with Portello. He would be the only foreign driver in a team of Italians. At St Cloud he failed to finish owing to atypical mechanical problems. Next, at Geneva, Wimille was unceremoniously punted off the track by (of all people) Tazio Nuvolari, while leading; he still managed to trail home in third.

Nuvolari chases Wimille at the Grand Prix des Nations in Geneva before bumping him off the track

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Then came the Turin race, where Wimille set a blistering pace. He was leading team-mate Varzi by a country mile (and had notched up the fastest lap in the process) when his pits ordered him to let the Italian by. Legend has it that he came to a halt 200 metres before the line, and calmly waited for Varzi to come by before he took the flag. Afterwards, Wimille just shrugged and suggested that, “If you are not willing to respect team orders, you might as well remain independent.” Sadly, the opinion of Signor Angelo Daffonchio, of Tortona, has not been recorded: the Italian national lottery was linked to this race, and Signor Daffonchio had drawn the ticket corresponding to Wimille’s car. Although the second place earned him 5 million lire, the team orders had cost him another 20 million lire.

Over the next two years, Wimille drove six more races for Alfa Corse. The Alfa Romeo 158 was by far the best car of its epoch, and perhaps this superiority has conspired with the Fates to deny Wimille the fame he deserves: having spent the Thirties racing substandard Grand Prix cars, it is ironic that the majority of fine drivers after the war did not have suitable machinery to compete with him. An indication of his ability can be seen, however, in his performances against team-mates Varzi, Farina, Trossi and Sanesi. Of these six races for the team, he won five and ceded another certain victory to Count Trossi in the other.