Farina stayed with the team for 1951, while contesting other events with his Maserati 4CLT/48. This 05 car was now obsolete, but as the new world champion Farina could negotiate good starting money.

This was the season when Alfa was finally defeated by Ferrari, and when Fangio emerged as clearly the quickest Alfa driver. Fangio took the title; Farina finished fourth in the points. Nino, though, was still a top-class driver, and his comparatively disappointing campaign was largely due to the Alfetta being at the end of its competitive tether. It was overstretched, and Farina did not have the delicacy of touch which Fangio had.

With Alfa Romeo withdrawing at the conclusion of 1951, Farina joined Ferrari, but like everyone else he was outpaced by his young team leader Ascari. This disconcerted him, although he and Alberto were close friends. For the first time in his life Farina had to try too hard, and he crashed a lot. Ascari was the fastest driver of the day — even Fangio acknowledged that — and he piled win upon win, leaving everyone else to pick up the crumbs. But it was still not a bad year for Farina — actually many grand prix drivers would have been very satisfied with it. He was regularly second behind Ascari, and finished runner-up in the championship, too — not bad for a man of 46. To put that in perspective, the runner-up in 2003, Kimi Raikkonen, will turn 46 in 2025!

Ascari continued his domination in 1953, by which time Farina had become a more thoughtful driver less inclined to take risks. He had fewer incidents, and the highlight of his season was winning the German GP after Ascari’s sister car shed a wheel. He remains, at 47, the oldest driver to win a world championship race without sharing a car.

Farina was also retained to drive Tony Vandervell’s Ferrari 4.5-litre 375 which was entered as the ‘Thin Wall Special’ in Formula Libre races in Britain. Given the usual state of the opposition this was akin to shooting fish in a barrel, but it was in this car that he became the first to lap Silverstone at 100mph.

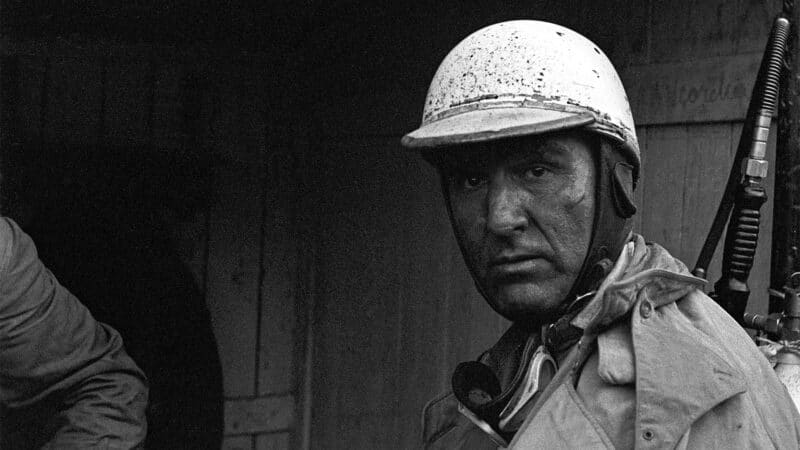

Farina leads Alfa Romeo team-mate Jean-Pierre Wimille in the Grand Prix des Nations at Geneva in 1946

Getty Images

The end of the season saw Farina third in the world championship — he grossed more points than Fangio in second place, but had to shed some — and he was the clear number two over at Ferrari, ahead of Mike Hawthorn and Luigi Villoresi.

Then both Ascari and Villoresi decamped to join Lancia and, at the age of 47, Farina became Ferrari’s number one. He rose commendably to the occasion, but he must have known that Ferrari was in deep crisis with no clear idea where it was going. Even so, in the Argentine GP which opened the season, Farina set pole and led the early stages, though a pitstop for a new pair of goggles perhaps cost him a win.

He then secured victories in the Buenos Aires 1000Km sportscar race (which was unusual because he rarely shone in endurance races), the Circuit of Agadir and the Syracuse GP. He crashed heavily while leading the Mille Miglia but seven weeks later, with his right arm still in plaster, disputed the lead of the Belgian GP with Fangio’s Maserati 250F until his Ferrari 553 developed a fault. Mercedes-Benz had not yet entered the world championship and so that drive at Spa was a good indication of his abilities; Farina revelled in Spa’s fast sweeps where his delicate car control came into its own and where the driver could make a real difference.

Then it all went wrong. While practising for a Monza sports car race, a universal joint on his Ferrari broke and the driveshaft punctured the fuel tank. The car caught fire and Farina was so badly burned that he missed the rest of the season. When he returned in 1955 he was able to race only by taking morphine injections to kill the pain.

With Moss and Fangio now at Mercedes-Benz everyone else faced an uphill struggle during 1955, but Farina still scored a second, a fourth and a third in the opening world championship races. Many drivers would be more then happy with that tally, yet we are speaking of a man pushing 50 and dosed-up on drugs…

It was too much even for Farina. The constant pain, together with the death of his friend Ascari, led Farina to announce his retirement.