750 MC National Austin 7 Rally

THIS well-known and well-attended event, the 20th of its kind, takes place on July 4th at the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu, Hampshire, and not at Luton as mistakenly announced…

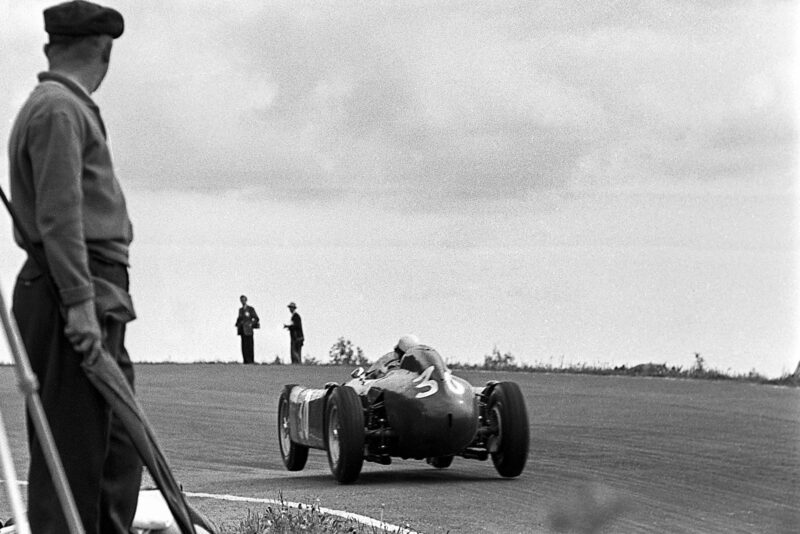

Alberto Ascari rounds Monaco’s Station Hairpin in the brilliant but ruinously costly Lancia D50

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

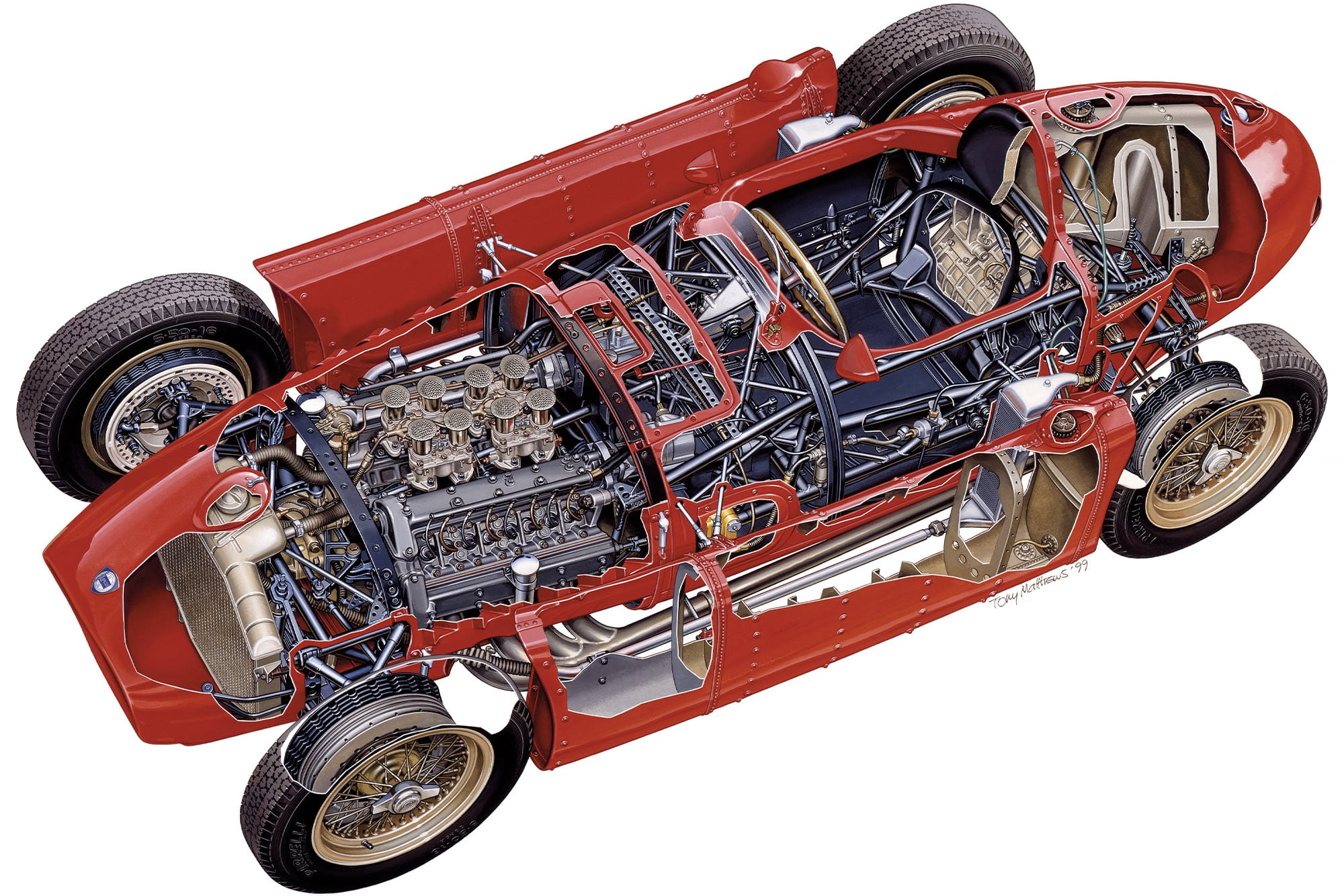

Rudi Uhlenhaut, the engineer behind the stupendous W196 Mercedes, described the Lancia D50 Formula 1 machine as “the only car we really feared”. Although the W196 and Maserati 250F were the highlights of the 1954-55 F1 campaigns, it was the stubby, compact, pannier-tanked D50s that would go on to have a lasting legacy.

This startling new 2½-litre F1 design was also, by the standard of the time, tiny. The D50 was the latest, and potentially the greatest, post-war product of the veteran engineer Vittorio Jano’s enduring genius. But while he was responsible for its overall concepts, he was not only assisted in its detailing by an outstandingly capable design team, he could also draw upon the frontier- technological capability of Lancia itself.

Ever since the vintage period of the 1920s, Lancia & C. Fabbrica Automobili had been famed for its technically advanced and highly sophisticated motor cars. By contemporary standards it offered the very best production car performance, handling and roadholding available anywhere on the global market. Post-war, the svelte Aurelia line emerged, and in 1950 when Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina styled the B20 Coupé with its sloping fastback tail treatment – making what Cisitalia and others had been doing look respectable – he set a trend for 2-plus-2 Gran Turismo cars, which was subsequently adopted by all other high-performance GT manufacturers.

“The F1 programme started just five months before the new formula”

However, when company principal Gianni Lancia decreed that the works team would no longer use the Aurelia Coupés after 1952, he set his heart upon building a true and specialised sports racing car series to project the sophisticated Lancia message to an international audience. His engineering team was headed by Jano, then 62 years old and rightly revered for his glory days with Alfa Romeo between the wars. For Lancia his engineers developed a superb series of ultimately 3.8-litre V6-engined sports racing and Competizione Berlinetta cars under the D-series programme, entitled Tipi D20, D23, D24 and D25.

Lancia won the dangerous and car- breaking Mexican Carrera Panamericana, the punishing Targa Florio and the majestic Mille Miglia through 1953-54. The next logical step for Gianni Lancia’s ambitions was to enter the new 2½-litre F1, which the FIA had announced for 1954-57. Big, roly-poly Gianni was the son of Vincenzo Lancia, the company’s founder and Fiat’s greatest racing driver of the pre-World War I period. Gianni ran the family company in conjunction with his widowed mother Adele. They authorised their experimental department to commence an F1 programme in August 1953, just five months before the new formula was to start. Gianni set the target of a debut at the French Grand Prix on July 4, 1954, the event at which Mercedes-Benz would make its re-entry into grand prix racing. Lancia signed double World Champion Alberto Ascari and his inseparable friend and mentor Luigi Villoresi, both from Ferrari, while Direttore Jano’s engineers in the Via Caraglia design offices knuckled down. When the F1 Lancia D50 finally made its debut in Spain, it was only the second totally new car, after Mercedes-Benz, to be built to the 2 ½-litre formula, because Ferrari, Maserati, Gordini and Connaught were all using enlarged 2-litre F2 equipment at that time.

Ascari and team with fresh-painted prototype D50 in early testing

Getty Images

Jano and his specialist engine designer, Ettore Zaccone Mina, decided that no matter the approach with a 21⁄2-litre unsupercharged engine, its ultimate power would never be spectacular. So to achieve optimum performance it was sensible to make it as small, compact, and as light as possible and install it in the minimum possible chassis structure. Having minimised size and weight, the finished car would have the best possible handling and traction to fully exploit the advantages of its good power-to-weight ratio. To save both space and weight, Jano employed his preferred V8 engine as a structural chassis member, its compact crankcase and heads accepting chassis loads where otherwise extra engine-bay triangulation tubes would be required.

Jano had selected a 90-degree vee configuration for his new engine, for both compact packaging and optimum structural integrity since it had to perform double duty as an integral structural member. The unit was angled within the chassis to pass its propshaft to the left of the driver’s seat into an offset transaxle input, enabling the seat to be dropped as low as possible within the high-sided cockpit.

On test, the new unsupercharged V8 engine developed 250bhp at 8000rpm. Initially its bore and stroke dimensions were 74 x 72mm, which meant a displacement of 2480cc, but alternatives were tried, including a short-stroke 76 x 68.5mm for 2486cc, and an almost ‘square’ alternative of 73.6 x 73.1mm, 2499cc.

Ascari tries D50 prototype in testing at Caselle airport as mechanic changes angled V8’s spark plugs

Getty Images

Naturally, the firm’s considerable preceding experience with V6 sports racing engines re-emerged in this new design. A chain-drive system for the twin overhead camshafts was one similarity, while the cylinder head structure itself also derived from the sports car units. The cylinder block casting was one-piece, in unit with the crankcase, in ‘siluminum’ light alloy with inserted wet cylinder liners. The cylinder heads were also designed as siluminum castings.

In prototype form, Lancia used special Weber carburettors tailormade to the V8, but when they gave trouble, Solex Type 40P11 twin-choke downdraught carburettors were adopted instead. They were fed with cool intake air through a nose-top duct. Ignition was by twin Magneti Marelli magnetos, driven off the inlet camshaft tails on each cylinder bank. The prototype D50 featured two neat magneto-cooling air scoops on its scuttle. Later a single central scoop was adopted, feeding cooling trunks to both magnetos and fitted with a flap, which the driver could open or shut as he pleased to help cool his nether regions…

With development, the V8’s power output would increase from around 250bhp at 7000rpm to a peak of some 275bhp at 8000rpm. This front-mounted power unit drove a propeller shaft connecting it to the rear-mounted transverse-shaft five-speed gearbox, final-drive and clutch assembly.

The car’s front suspension fed loads directly to the engine, demanding peerless precision in manufacture. Each complete D50 chassis was precision surface-finished under a giant Genevoise GSIP machine, all mounting faces on the frame being machined in situ to exceptionally fine tolerances.

The chassis itself was a welded steel multi-tubular spaceframe in c30mm tube stock derived directly from D-series sports car experience. Abaft the cockpit, the large transaxle casing provided additional structural duties to support the transverse leaf-spring for the rear suspension and also to locate the de Dion tube’s central sliding- block guide.

Jano had tirelessly investigated the science of suspension behaviour, cornering and handling. He had studied the complex variables involved in combinations of weight distribution, dynamic weight transfer and suspension geometries, castor, camber change, the effect of roll-centres, etc.

While his preferred front suspension was independent by coil and wishbone, he adopted the de Dion axle system with a transverse leaf-spring at the rear. The de Dion tube was small and light by contemporary standards, curving behind the differential housing and located fore- and-aft by parallel radius rods on each side. A sliding block system on the back of the final-drive case provided lateral control.

Inboard space was at a premium in this compact little package, and so the drum brakes were mounted outboard. Jano had minimised the new car’s wheelbase by abandoning the successful inboard-mounted brakes of the sports car in favour of this all- outboard system. Then, to concentrate fuel load well within the wheelbase, he conceived the D50’s most distinctive feature, two long pannier fuel tanks outrigged along each side of the car between its front and rear wheels. They ensured minimal handling change between full and empty tanks, and Jano also believed they would help clean up aerodynamic turbulence – and therefore drag – between the wheels. The Lancia D50 emerged notably short, squat and light. Its centralised weight concentration imparted a low polar moment of inertia, making it the nimblest of contemporary F1 cars. It consequently required a sensitive and capable racing driver to exploit its attributes to the maximum, without the layout’s inherent ‘nervousness’ then denting his confidence in the car.

Eugenio Castellotti

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Despite three-wheeling up Raidillon, Castellotti retired with gearbox trouble

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Everything about the new cars and the works team, from its gigantic Lancia Corse transporter to the well-pressed blue overalls the mechanics wore, and all their carefully thought-out tailor-made equipment, exuded impeccable toolroom class and quality, with that indefinable addition of Italian style and flair.

After a protracted and delayed development period, which led to several early race entries being cancelled through the new formula’s maiden season of 1954, two new D50 cars finally ran in their public debut in the late-season Spanish GP at Barcelona. Despite both Ascari and Villoresi retiring there, they had created a great impression. After extensive testing at Monza and, extraordinarily, on the Sanremo street circuit, fuel tankage was increased from 160 to 200 litres to enable D50s to tackle a 500km GP non-stop. A full team of five D50s was flown to Argentina for the opening round of the 1955 World Championship.

“Had Ascari not crashed into the Monaco harbour, he could have won”

Out there the cars could not handle adequately on the Buenos Aires Autodrome’s geometrical curves. Both Ascari and Villoresi spun off, the former after leading laps 5 to 22, the latter in young Castellotti’s car after his Lancia’s fuel pump had failed. It seemed that the D50s’ intentionally neutral-steer characteristics certainly gave a high level of adhesion in high-speed curves, but the drivers received little warning of an incipient breakaway, and when either the front or rear tyres lost adhesion they did so almost instantaneously, and with little chance of recovery.

Lancia’s home race, the Turin GP in Valentino Park, followed on May 27. An extra 15bhp had been squeezed out of the engines – 106bhp per litre – and starting from pole position Ascari won impressively after pressuring Luigi Musso into running his leading works Maserati 250F off the road. Castellotti and Villoresi finished third and fourth. On Easter Monday, 1955, the team contested the Pau GP in southern France; Ascari had looked certain to win until a rear brake pipe split. He continued after a stop, with only front brakes operative, and still finished fifth. His team-mates’ D50s placed second and fourth.

Ascari then qualified on pole yet again for the Naples GP at Posillipo on May 8, winning easily while Villoresi ran only third. There was no team car available for Castellotti that weekend, but these were immensely encouraging results. Two weeks later, Lancia Corse entered the season’s first European round of the World Championship, the Monaco GP, in force, with four D50s for the usual works trio plus 56-year-old Louis Chiron, the local ace who had won the 1954 Monte Carlo Rally in a Lancia Aurelia.

Pride before the fall: four of the five D50s in the Monaco pits, 1955. A magnificent sight

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

A fifth D50 was also on hand as a practice muletto, and Lancia’s paddock line-up looked truly magnificent. Ascari qualified on the front row alongside two Mercedes-Benz W196s. In the race, he couldn’t hold back the German cars until all three struck trouble. Then, just as Ascari was approaching the end of the lap – which would have seen him pass Moss’s leading Mercedes, by this time stationary in its pit – he slid on spilt oil at the harbourside chicane and crashed clean through the quayside straw-bale barrier to plunge into the harbour. His car vanished in a smother of spray, steam and straw, shocked spectators bursting into cheers of relief as Ascari’s bright blue helmet broke the water’s surface. Boatmen recovered him barely injured, save for a broken nose, shock and a soaking. His battered, salt-water streaming car was winched out that evening.

Castellotti had been delayed, but he salvaged second place for Lancia, while Villoresi and Chiron finished fifth and sixth. Had Ascari not crashed, he could have won. Lancia Corse salvaged its car, but not the company’s independent future.

Ascari’s D50 in the Gasworks Hairpin, 1955 Monaco GP, before his dive into the harbour

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Having forsaken sports car racing for F1, Gianni Lancia allowed his contracted drivers to take other sports car rides. Four days after that Monaco ducking, Ascari accepted Castellotti’s offer to try his brand new works Ferrari 750 Monza sports at Monza; the car left the road in the high-speed left-hand curve at Vialone, and he was killed.

Italian racing was devastated. Poor Villoresi – Ascari’s lifelong mentor and friend – would not contemplate racing again for some time. The Lancia Corse racing programme had been built largely around Ascari and his skills. Now it simply collapsed. Gianni and Adele Lancia decided it would not compete again until a later date, although Jano was permitted to take one car to the Belgian GP for Castellotti as a private entry.

“At Monza four D50s emerged, standard except for prancing horse badges ”

There the youngster covered himself in glory during practice, beating all the Mercedes W196s for pole position. But in the race, he could not string together such rapid laps, and after running third his car’s gearbox seized. Behind the scenes, Lancia was in dreadful difficulty. For five wild years, Gianni Lancia had permitted his engineers’ creativity to run riot, almost regardless of cost. The company’s finances collapsed, with the Italian press avidly stoking the fire of its insolvency. Beset by anxious creditors and labour unions, the Lancias, mother and son, decided to sell it to cement and finance millionaire Carlo Pesenti. The family lost control of the great Vincenzo’s creation. But the Lancia Corse hardware was too valuable and had too much potential to go to waste. After protracted further negotiations involving Lancia, Fiat and Ferrari – and probably some prompting from the Italian government – Gianni Lancia’s friend Agnelli of Fiat donated some £30,000 annual sponsorship to Ferrari if it would continue to race the D50s against Mercedes for its country. This was a great coup for Mr Ferrari, whose own outdated cars had become obsolescent and uncompetitive. Now he had fallen heir to the world’s finest F1 machines outside Stuttgart.

On July 26, 1955, a formal ceremony at the Turin factory witnessed six of the eight D50s handed over and transported to Maranello, accompanied by spares, drawings, tools, transport and an almost complete streamliner body, intended for the Italian GP at Monza. Engineer Jano was obliged to leave Via Caraglia in a new-broom operation by Pesenti, so he followed his D50s to Maranello. Initially, it was rumoured that the powerful, compact and lightweight Lancia V8 engine would appear in a Ferrari chassis, but in practice for the Italian GP at Monza, four D50s emerged in completely standard form as before, save for fresh Ferrari prancing horse badges. But all of them encountered terrible Englebert tyre problems on the new banked speedbowl section and, rather than risk an accident, all four were wisely withdrawn before the GP. It was a bitter blow for Italy, as they were the only Italian cars with any hope of challenging Mercedes.

De Portago in what for 1956 had become a Lancia-Ferrari. It would bring the title for Fangio

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

This incident truly highlighted the obsolescence of Ferrari’s Belgian Englebert tyres compared to the Pirellis around which the Lancias had been designed. Then two D50s were taken to England to run in the minor Oulton Park Gold Cup race, driven by Hawthorn and Castellotti, but neither handled well on the parkland circuit, and Hawthorn merely inherited his second place. For 1955, Ferrari would work hard to develop the D50 into a more handleable, user-friendly proposition for his drivers, and Juan Manuel Fangio would make the most of it, winning the 1956 World Championship in Lancia-Ferrari cars, while team-mate Peter Collins also shone brightly, winning his first grands prix.

In retrospect, the compact, low polar moment, centrally weight-concentrated Lancia D50 was a matching predecessor to Jackie Stewart’s Derek Gardner-designed Tyrrell 005-006 cars of 1972-73. Once developed, both designs brought World Championship honours to truly great racing drivers. But for Alberto Ascari, and the Lancia family, the introduction of the glorious D50 had led to disaster…