Lunch with... Roy Salvadori

Britain’s busiest 1950s racing driver remembers the battles and the parties

James Mitchell

When I was first taken, as a small boy in the 1950s, to Goodwood, Silverstone and Castle Combe, Stirling Moss was of course the man we all wanted to see. But probably the second biggest draw in British motor racing, the darling of the crowds for his flamboyant speed and the ruthlessly determined way he drove to win, was Roy Salvadori. A typical national meeting would have separate races for F1, Formula 2, sports-racing cars big and small, saloons and formule libre. As likely as not the tall, debonair Englishman with the Italian name would be in all of them, in a variety of cars: invariably he would be challenging for the lead, and frequently he would be taking it.

Roy earned his living by racing other people’s cars, and the combination of a strong work ethic and generous start, prize and bonus money meant that, by the standards of the day, he made a lot of money. But it also meant that he would usually opt for a busy British weekend with half a dozen races at two circuits, rather than an overseas Grand Prix that might offer international glory but less cash.

He invested his racing earnings shrewdly in his own motor businesses, ending up with both a BMW and an Alfa dealership, and when he sold out in 1971 he retired to Monte Carlo. So it’s in his superb apartment on the start-finish straight of the Grand Prix circuit, overlooking the harbour, that his wife Sue serves us an excellent lunch. Sue, incidentally, must be the only girl in the world who is both the daughter of and the wife of a Le Mans winner: her father John Hindmarsh won for Lagonda in 1935.

Roy was born in Essex, of Italian parents, in 1922. In 1946 he went to look at an MG he’d seen advertised: he thought it was a sports car, but it turned out to be an R-type single-seater. He bought it anyway, took it to the first post-war British race meeting, at Gransden Lodge, and came second in his first race. “Maybe I should point out,” he says modestly, “there were three starters and two finishers.” The MG was followed by the ex-Dobbs Riley Special. He got it checked over by Monaco Motors of Watford and was horrified when the manager, one John Wyer, presented him with a bill for £15. But in those immediately post-war days old racing cars were cheap, and in 1947 he bravely bought, in half-shares with a friend, the ex-Nuvolari, ex-Kenneth Evans Alfa Romeo P3 Grand Prix car. “It scared both of us. The first race I did with it was Chimay, a very dangerous circuit, partly with a loose surface. The Alfa weaved all over the place, took up the entire width of the road. When you overtook another car you were never sure which side you’d pass it. Everything was very new to us: we didn’t have any experience. The gearbox was playing up, so I did the whole race, start to finish, in top gear. I finished fifth. But it made a nice holiday.”

A 14-year-old Maserati 4C followed, which Roy ran in the 1948 British GP at Silverstone, and in 1949 he campaigned a more modern 4CL Maserati which was prepared by Prince Bira’s White Mouse Garage in Hammersmith. That car was destroyed in a fiery accident during the Wakefield Trophy in Ireland, and financial constraints kept Roy out of racing until 1951. By now competitive single-seaters were more expensive, so he bought a Le Mans Replica Frazer Nash.

“My first meeting with it was the May Silverstone in 1951. I was leading, a big thing for me then, ahead of Bob Gerard, Tony Crook and the other Frazer Nashes. So I was feeling pretty good about life. At Stowe we came up to lap a group of slower cars which were having their own battle. I tried to overtake them all, but it couldn’t be done. I got on the loose stuff.”

Thanks to a newsreel cameraman who happened to be on the spot, the horrifying accident that followed was later seen in cinemas up and down the country. The marker drums that delineated the airfield track were filled with concrete. The Nash hit them and cartwheeled into the air, over and over. Roy was half thrown out but caught his feet in the steering wheel and was flung around like a doll, with the car rolling over him. Among other injuries, he sustained a triple skull fracture and brain haemorrhaging.

“Crash helmets weren’t mandatory then. I didn’t wear one: they were expensive, and you saw the Italian stars like Farina in their leather caps, and you thought, that’s the thing, that looks good. Anyway, at Northampton hospital they decided they could do nothing for me, and pushed me into a corner. They rang my parents, but told them I was unlikely to be alive by the time they got there. A priest was summoned and gave me the Last Rites.

“But I proved them wrong. I slowly recovered. My face was pretty bashed about, and I had a dreadful persistent ringing in my right ear. I’ve had to live with that ever since: I’m completely deaf on one side. In all my racing after that I could never really hear what the engine was doing. I just worked off the rev-counter and the gauges, and the vibration through the seat of my pants. I was never any good at Le Mans starts, because I couldn’t hear the starter or when the engine caught. Once I brought my Aston into the pits complaining of a misfire, and when they opened the bonnet they found there was a rod out the side.”

Three months after the Silverstone crash Roy was racing again, in an XK120, and during 1952 he raced that and the repaired Frazer Nash. The accident hadn’t slowed him, but costs were mounting, and from then on he raced other people’s cars. Wealthy Irishman Bobbie Baird offered Roy his Ferrari Tipo 500 for the 1952 British Grand Prix. This led to several more races in Baird’s 2.7-litre sports Ferrari, which they shared in the Goodwood Nine Hours. The rules said that no driver should do more than two hours without a break, so every two hours Baird was sent out to do one lap before Salvadori got in again. He got the Ferrari up among the works Jaguar C-types and Aston Martins, and then into the lead. A dead battery and a black flag for a faulty rear light dropped them to third by the end, but John Wyer, now Aston Martin’s racing chief, was impressed.

“Bobbie Baird was such a nice chap. His father owned the Belfast Telegraph, a very big paper in those days. Bobbie had a drink problem, but they dried him out a couple of times, and the second time it worked. He married his nurse, Isobel. Then he bought a new 4.1 Ferrari, a terribly nasty car. In morning practice for a Snetterton meeting he turned it over. I was in the same session, so I stopped. He’d been thrown out, but he seemed to be all right, just winded. The marshals were looking after him, so I got back in my car and went back to the paddock. Then I heard he was dead: a broken rib had punctured a lung.”

In 1953 Roy signed for Connaught in F1 and F2 events, and Aston Martin in major sports car races. When these commitments allowed he also drove for Ecurie Ecosse in its C-type Jaguars, and for Syd Greene in the Gilby Engineering 2-litre Maserati A6GCS. Syd was a tremendous enthusiast who was prevented from racing because he’d lost an arm in an accident. His teenage son Keith was as keen as he was, and went on to a life-long career in racing, first as a driver and then as a brilliant team manager. In 1954 Gilby added an F1 Maserati to the stable, and the green 250F was Roy’s main mount in single-seater races for three seasons. Much of the money for the Maserati’s purchase came from Esso, which also paid Roy a £10,000 a year retainer to remain loyal to its fuels and oils. A typically busy day was the June Snetterton in 1954, when Roy ran the two Maseratis and a C-type in six races and scored four wins, a second and a third.

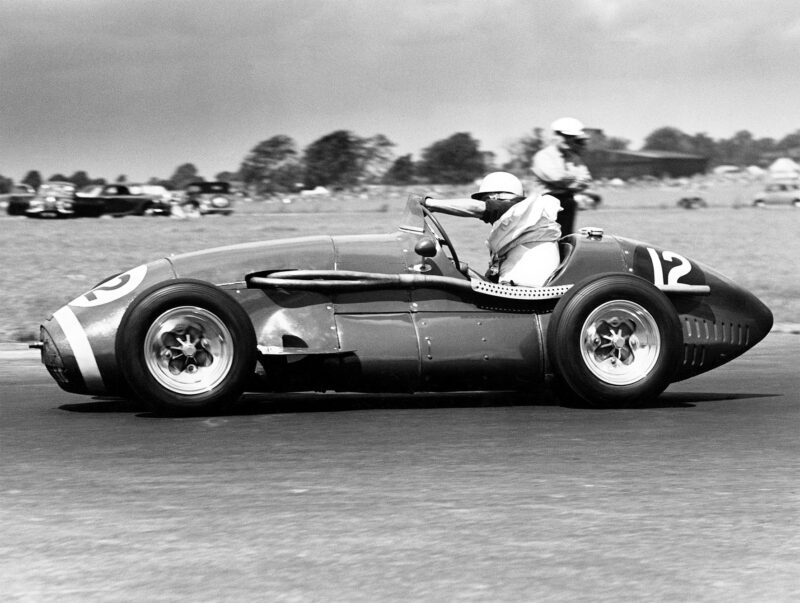

Crash helmet and flapping shirt in the 1952 Connaught

Motorsport Images

“Sometimes I raced four or even five cars in one meeting. Some had left-hand changes, some right-hand changes. The 250F had a central throttle pedal. Torque curves, rev ranges, braking points, gearchange points, they were all different. I’d try not to talk to anyone between jumping out of one car and into another, to keep my concentration, but basically it was instinctive. I don’t know how I did it, really.

“I’d clear about £27,000 in a good year, which was a lot of money in those days. I had a simple deal with Syd Greene: the mechanics got 10 per cent of all start and prize money, and we split the rest 45/45. But Esso would pay a big bonus for a win, because they liked to use it in their press advertising. Second place was no good to them, so it really mattered if you won. But at Aston Martin John Wyer would pool the start and prize money and split it equally between the drivers, so we all got the same amount whether we won, or finished fourth, or retired.

“I did have a reputation as a hard driver with certain people. I wouldn’t be hard with most of my team-mates, but there were some tough drivers about, and you just had to hit back. If you were being deliberately baulked, you had to let them know you were quite prepared to put your car where there might be a shunt. If you did that often enough they’d respect you.”

A memorable confrontation was Roy’s tussle with Ken Wharton’s V16 BRM at the 1954 Easter Monday Goodwood. The BRM was chucking out oil and fuel, and Roy in the Gilby 250F was being badly held up, but he couldn’t get past. Getting angrier and angrier, he tried to force his way past at Lavant Corner. “Ken was a hard driver too, and he wasn’t going to let me through. We collided, and we both spun. We both restarted, but my clutch exploded a lap later, bits of shrapnel came out through the bodywork, and Ken won the race. We didn’t have a nasty scene afterwards or anything like that. We just didn’t talk to each other – which in the friendly atmosphere of motor racing then meant just as much, really. Later the Duke of Richmond & Gordon sent me a silver cigarette box and on it was engraved ‘In acknowledgement of a splendid show at Goodwood’. So I thought, well, he realises I was robbed of that race – until I found out he’d sent exactly the same box, with the same inscription, to Wharton!”

A stand-out Ecurie Ecosse drive came in the 1953 Nürburgring 1000Kms. Roy did the first stint, with the C-type not particularly happy over the bumps, but soon after his co-driver Ian Stewart took over he came in to say the car was handling so badly that it should be retired. Roy got in again and drove to the end. “It was completely falling to pieces. Every 14-mile lap I’d come round thinking, I’ll stop this time, but then as I approached the pits I’d say to myself, I’ll just try one more lap. I wouldn’t say I liked the Nürburgring. I respected it. You’d look forward to a race there, and once you got there you’d wonder why you’d been looking forward to it. Anyway, we finished second, and then as Wilkie Wilkinson of Ecurie Ecosse was taking the C back to the paddock the front suspension collapsed. The fuel tank had come adrift, too, and was only being held in place by the body.”

Roy’s contract with Aston Martin, having started in 1953, endured more than a decade. He had a great relationship with the often terrifying John Wyer. “He was marvellous. You really wanted to do well for him. He was very methodical, kept detailed notes of every race, with extremely frank comments about the performance and behaviour of every driver. It was a wonderful team – drivers like George Abecassis, Peter Collins, Reg Parnell. We used to party pretty hard. I can’t believe what hooligans we were. At one hotel a sofa got pushed through a plate glass window and the police were called. Fortunately the copper who interviewed me didn’t seem to know much about motor racing, so I gave my name as M. Hawthorn of Farnham. Parnell was the instigator of a lot of it. He was bloody quick, too, such an under-rated driver – he could sort out most of the Aston team. George was great company. He used to say, ‘When I crash an Aston Martin, I get a bollocking from Wyer. In the war, when I crashed my aeroplane, I got a medal.’ You can never replace these people.

Bare-headed and besuited in the Dobbs-Riley from 1946

Motorsport Images

“At Le Mans in 1955 the rule was that, whatever order the Astons were in at the end of the first lap, we should stay like that, so we didn’t race each other and wear our cars out. Well, Peter Collins and I had the most terrific dice, swapping places all round the circuit, and then when we approached the pits we would sort ourselves into the right order so it looked like we were behaving ourselves. On one lap I was trying so hard I spun at Arnage, and Peter waited for me while I got going again, roaring with laughter. Peter was such a nice chap.

“The sports car race at the 1956 May Silverstone was a bit of a story. There were four DB3S Astons for Stirling, Peter, Reg and me. There were six D-types, including Mike Hawthorn and Des Titterington. My DB3S was actually my own car, which I’d bought from the works on the basis that they could borrow it back when they wanted. Des and I made joint fastest practice time. Stirling’s contract gave him the pick of the cars, but when he asked John Wyer to try mine John pointed out that he would have to ask me, as it was my car. Well, he didn’t ask me: if he had I’d have let him have it. But he asked me to try his car in practice, and I told him I preferred it with the 6.50 tyres – he’d opted for the 6.00s. He was changing down for Stowe, and I was taking it in top. The downside of that was that unless you got it right you’d be understeering off the circuit, whereas in third you’d be right in the power band and you could just floor it to get some pull from the back.

“Stirling led away from the Le Mans start, but I screwed myself up and went by on the inside under braking for Stowe, and unfortunately I pulled two works D-types through with me. Then at the next corner, Club, a D-type came nosing up the inside. I assumed it was Mike, so I moved to the right, so he would have to go round on the outside. I knew Mike would know the score, he’d know Salvadori wasn’t going to let him through on the bloody inside. But he kept coming and I thought, ‘Oi, Hawthorn, you’re making this a bit dangerous.’ What I didn’t realise was that it wasn’t Mike, it was Titterington. Then the Jaguar spun in a cloud of rubber smoke, and Collins and Parnell in our Astons and an Ecosse D-type crashed into him. It was a four-car pile-up.”

Salvadori went on to win from an aggrieved Moss, and there was an enquiry afterwards, as some felt that Salvadori had squeezed Titterington at Club. “The only verdict they reached was that we should all be more careful on the first lap. Well, it’s no bloody good telling a racing driver that, is it?” But Roy took no part in the enquiry because, having also won the small sports car race earlier in the day in a works Bobtail Cooper, he was once more in Northampton hospital. Fighting for second place with Archie Scott-Brown’s Connaught in the Formula 1 race, the Gilby 250F had broken a driveshaft, locking up the rear wheels, and the car hit the bank at Stowe and overturned.

The high point of Roy’s Aston Martin career was of course the 1959 Le Mans 24 Hours. “I didn’t really like Le Mans, but I loved the week we’d have there, staying at Aston’s hotel at La Chartre. In 1958 I’d been partnered with Stuart Lewis-Evans, who was probably seven inches shorter than me, but for 1959 I was with Carroll Shelby. We were the same height, so we could make ourselves comfortable in the car. But Carroll was suffering from a stomach bug, so I drove for 14 of the 24 hours. We were in the lead by 10pm, but four hours later the car developed a dreadful rear-end vibration. I stopped at the pits but they could find nothing wrong, so I continued, but it got worse and the car was bouncing all over the road. I went slower and slower. I thought it was probably transmission, which was always the DBR1’s weak point. When I came in for my fuel stop they discovered that the offside rear tyre had lost part of its tread. We’d now lost the lead to the P Hill/Gendebien Ferrari, and I had a terrific row with Reg Parnell, who said, ‘You silly bugger, why didn’t you realise it was the tyre?’ That upset me and I must have said something, because there was a very tense atmosphere in the pit until John Wyer calmed us all down.

“The Ferrari was now three laps ahead, and we needed to make up the lost ground. What you have to do if you want to drive as fast as possible at Le Mans is stick rigidly to the rev limits and not make any duff gear changes, but be absolutely flat out as far as braking and cornering are concerned. That’s because brakes and tyres can be replaced, but the engine and gearbox can’t. If you look at the lap times, even while we were saving the mechanicals, you’ll see we were going like hell. We whittled away, kept the pressure on, and then at 11am on Sunday the Ferrari blew its engine.”

After 10 years of trying, Aston Martin had won Le Mans. If it could win the Tourist Trophy at Goodwood, it could take the World Sports Car Championship from Ferrari. Roy was paired with Stirling Moss for this race: Stirling led from the start, Roy consolidated that lead during his stint, and when he brought the DBR1 in to hand back to Stirling they were three minutes ahead of the sister car of Carroll Shelby and Jack Fairman. “I made sure I’d left the car in first gear for Stirling, and then as I was about to get out of the car I felt wet on my back. The fuel was coming out of the hose before the mechanic had got the filler cap open. Then we were on fire. I leapt down the bonnet, kicking the mechanic who was changing the front wheel on the head, and rolled over and over on the little strip of grass between the pitlane and the track. Then an ambulance man wrapped me in his coat and got the flames out.” Stirling took over the Shelby/Fairman car, drove it for the rest of the race and won. His burns bandaged, Roy watched from the pits as Aston took the title.

He began the 1957 F1 season with a BRM contract. “Raymond Mays could really lead you up the garden path. He was very charming when he wanted to be, made you believe he could make you World Champion. Because BRM had had a lot of braking problems, I specifically agreed with Ray that only Lockheed should be allowed to develop and modify the brakes. First time out at Goodwood I spun in practice when a brake locked. Then on the warm-up lap they all locked on. It happened again on the first lap of the race. The marshals couldn’t push the car and had to heave it off the track. Ray promised me Lockheed would be summoned to sort out the brakes before the next outing, which was Monaco. In qualifying there the brakes were still jamming on and I failed to qualify. At the hotel I bumped into the Lockheed rep, who said BRM had made their own modifications to the braking system and had not involved Lockheed. I found Raymond Mays, told him what I thought about it, and left the team forthwith.”

He had a couple of Vanwall drives at Rouen and Reims, and then concentrated on his rides with Cooper, which was doing more and more F1 events with 1500 and 2-litre Climax power. He and Jack Brabham made a good team, and in 1958 Roy’s little 2.2 Cooper was second in the German GP, third in the British GP and fourth in the Dutch. Any pleasure he might have felt from the second place at the ’Ring, his best ever Grand Prix finish, was wiped away by the death of his friend and former team-mate Peter Collins; but that season he was fourth in the World Championship behind Hawthorn, Moss and Brooks. “In the Cooper team old Charlie Cooper kept it all together. He was the businessman, the disciplinarian, and he always told John what to do. When we got back from a race on Monday, Charlie would ask John to hand over the start money, then he’d go through John’s pockets to see if he’d kept any back.”

Aston Martin was now developing its DBR4 Grand Prix car, and Parnell approached Roy and Jack Brabham to drive it. They agreed verbally, but then Coventry Climax told Cooper that it was preparing a full 2.5-litre engine for the new season, and John Cooper tried to get Jack and Roy to stay. Jack agreed, and of course went on to be 1959 World Champion. Roy, having given his word to his old friends at Aston Martin, stood by his verbal agreement.

Moss (21) leads Salvadori away during controversial 1956 May Silverstone meeting

Motorsport Images

But the nimble little rear-engined Cooper made the Aston out of date almost before it appeared. Apart from second place in its first outing at the 1959 May Silverstone, the DBR4 was never competitive. Nor was its 1960 replacement, the lighter, all-independent DBR5. In 1961 Roy drove for the Yeoman Credit team of F1 Coopers, and in 1962 for the Bowmaker-backed Lola team alongside John Surtees, which produced a string of retirements. But he was as busy as ever in British racing. At Crystal Palace he raced four cars in four races – Yeoman Credit Cooper and E-type, Cooper Monaco and Jaguar 3.8 for Coombs – and won all four. Then at Oulton, in the 3.8, a tyre burst at Cascades and he went upside down into the lake.

“When I undid my seat harness I was floating inside the car. My chest was exploding and I started to swallow water. I thought, what a way for a racing driver to die, by drowning. I was trapped until a marshal got one of the back doors open and pulled me out.” Soaked and black with mud, he was given a lift back to the pits by 3.8 rival Graham Hill, put on some clean overalls and went out to practise the F1 Lola for the Gold Cup. He qualified on the third row, but a broken throttle cable put him out of the race.

“When we raced at Oulton Park we used to stay at the Chester Country Club. You never booked in those days: you just arrived. One year [private entrant] Tommy Atkins told me I had to behave myself and get a decent night’s sleep before the race. So I took a single room and went to bed early. I’d just got to sleep when there was a knock on the door, and the hotel manager said, ‘I’ve got a young lady here who says she does your timing, can she sleep on your floor?’ In she came, and I’d just got off to sleep again when there was another knock. It was Jim Clark, complete with girlfriend, with nowhere to sleep. They squeezed in, too. I got no more sleep that night because Jimmy snored.

Roy was fourth in 1951 F1 World Championship for Cooper, including his third at Silverstone

Motorsport Images

“Another time we were having a bit of a party and I counted 41 people in one hotel bedroom. The lady in the next-door room was knocking on the wall saying, ‘My husband’s a racing driver, he needs to sleep. If you don’t quieten down I’ll send him in to sort you out.’ After a while there was a knock on the door and Graham Hill came in, very pompous, but in no time at all he was having a beer. In the end a tearful Bette came in and asked him to come back to bed.”

Having driven privately-entered DBR1s at Le Mans in ’60 and ’61 – he finished third in 1960 with Jim Clark – Roy was offered Briggs Cunningham’s Tipo 151 Maserati for the 24 Hours in 1962. But he couldn’t squeeze his tall frame into the Maserati’s coupé body, so he shared Briggs’ E-type instead, and they finished fourth overall and won their class. In 1963 he was in a Cunningham E-type again.

“On Saturday evening I was going through the Mulsanne kink, which was just about flat in the E – you had to feather the throttle just a bit – and suddenly I felt the car sliding. Oil.” Bruce McLaren’s Aston Martin had blown its engine comprehensively moments before. “Several people had already gone off, so I was a late comer, so to speak. There were cars up the bank and in the trees. An Alpine was on fire on the other side of the track – that was a Brazilian called Bino Heinz, he was burned to death. I hit the bank with a huge impact, and somehow I was shot out through the E-type’s back window onto the road. I was lying on the tarmac and there was another driver nearby, unconscious [Jean-Pierre Manzon, whose René Bonnet had also gone off]. I was drenched in fuel because the tank had ruptured, and I remember the E-type’s horn going off, this weird sound, and then it all flared up. I was lying in the road soaked in petrol, my car was burning and the flames were coming along the trail of petrol towards me. But I literally couldn’t move. Finally I stretched my hands out, managed to get my fingernails into the grass verge and pulled myself up this little earth mound. That’s all I remember. In the early hours Sue came to the hospital and sneaked me out, drove me home to England.”

Through the early 1960s the hectic British racing schedule continued in cars as diverse as Ferrari 250LM, Cooper-Maserati and AC Cobra. His last works Aston Martin drive came with the team’s swansong in the Coppa Inter-Europa at Monza. Roy’s Project 214 Aston battled wheel-to-wheel throughout the three-hour race with Mike Parkes’ Ferrari GTO until, in the closing laps, Roy outfumbled Mike among the backmarkers and won what Wyer regarded as the finest victory of his career. Wyer then left Aston for the Ford GT40 programme, and asked Roy to be involved in its development. “The early GT40 was a big disappointment. There was something peculiar about it: it wasn’t a nice car, and I had no confidence in it,” says Roy. “We eventually discovered the aerodynamics were all wrong, and the back wheels were coming off the ground. I reeled off all my complaints to John Wyer, and he sighed heavily and said, ‘Anything else, Salvadori?’ I said, ‘You don’t believe me, do you? I’ll give you a demonstration.’ So I took him round MIRA, and I showed him how the doors were lifting so much at 150mph that I could put my hand through the gap. He said hastily, ‘Put your hands on the wheel, Salvadori, drive the thing.’ I said, ‘Look at the bloody bodywork, it’s swelling.’ Then there was this explosion and the front bodywork disintegrated, all there was left were shreds of fibreglass and the remains of the wire fixings. But I did drive a GT40 in my last race, at Goodwood in 1965. I finished second to a CanAm McLaren, and won the GT category.”

In 1965 the Chipstead Group, with which Roy was involved, bought Cooper, and he found himself racing manager of the Cooper F1 team. It was the twilight of the team’s F1 days, but they had young lion Jochen Rindt, and when John Surtees fell out with Ferrari in the middle of the 1966 season they had him, too.

“We managed to get on with John Surtees, which was an achievement in itself. He was so angry with Ferrari, so determined, that he went well for us. So did Jochen, so did Pedro Rodriguez. Some of Jochen’s races with the car were fabulous. But John Cooper couldn’t bear it that we were paying Rindt £50,000. He didn’t understand that by having Jochen, who was a brilliant driver and a rising star, we were much more attractive to sponsors. We weren’t paying the money, the sponsors were. If we’d run an unknown driver we wouldn’t have got that backing.”

Talking to Roy evokes an era of motor racing that has disappeared: the friendships, the rivalries, the parties, the accidents. Roy himself is surprised that he’s still here to tell the tales.

“I never reckoned I’d be around to retire. I was sure it was all going to come to an end with a big accident. All of us used to think that. We wouldn’t have been human if we didn’t. I’d given myself a span, I thought I knew exactly when I was going to buy it. I just hoped my accident was going to be a big one so I didn’t have to linger. You knew it was bloody dangerous, but you didn’t want to stop.

“Anyone who can come back from a painful accident and still be as fast as he was before must either be brave or thick. I suppose in my case it was a bit of each.”