“I kept thinking, ‘How on earth does one steal a march on the rest?’ Really what we were looking for was another 50 horsepower, but where were we going to get that particularly bearing in mind that I was working for a man for whom the Ford Motor Company was the only company in the world?”

Gardner went through his files and plucked out the proposal he had originally sent to Granatelli. After doing some calculations, he concluded that if he had a car with four front wheels and two rear wheels, he could reduce the amount of lift generated by normal front wheels which would in turn allow him to back off on the front aerodynamics. “Hey presto! My calculation was that that would equate to 40-odd horsepower. When I showed everything to Ken, he said, ‘Good grief! What’s this?’, but actually it wasn’t as difficult to sell him the idea as I’d expected.

“On the way back from the 1975 South African Grand Prix, I talked my way into First Class for a bit, in order to talk with Jackie Stewart about it. I don’t know if it was turbulence or something in his drink, but he had a fit of choking! He’d never seen anything like it before.”

Once the idea was accepted in principle, the first task, of course, was to find a tyre supplier. Tyrrell was contracted to Goodyear which raised no objections and promised support. “Leo Mehl asked what size we’d want and I said, ‘Well, ideally I’d like nine-inch…’ We compromised on 10, which was Mini-size, of course. People always wondered how we kept the project secret, but we operated a very simple principle, and it’s still the most reliable: if you don’t want people to know, don’t tell them! Yes, the Goodyear people knew about it, but there were a lot of racing Minis in those days, with people doing peculiar things with them, and they had small wheels, so perhaps that helped provide a bit of fog…”

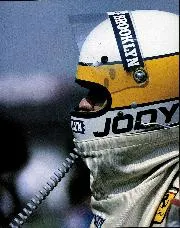

Despite his misgivings, Scheckter took the quirky Tyrrell’s only win at Anderstorp ’76

Grand Prix Photo

From the rollover bar forward, the first P34 was a new car, but fundamentally a simple one: “The rear was straightforward 007 (the 1975 four-wheeled car) just bolted on. It was very much the prototype didn’t have any bag tanks in it, for example: it was purely a test vehicle, but weighted up to what I thought the race car would probably be. In fact, the aerodynamics were fairly appalling, so it didn’t gain anything from that, but inherently it was quicker than 007 the turn-in, and so on, was marvellous. After testing at Paul Ricard, in late ’75, we started work on building the proper race car.”

The P34 made its debut at Jarama, round four of the 1976 World Championship. Only one car was entered for Patrick Depailler, Jody Scheckter sticking with his regular 007, which qualified 14th – 11 places behind the six-wheeler…

“Jody,” said Gardner, “would drive the P34, but you knew it wasn’t with total commitment. He did win at Anderstorp but, you know, you’d see his head go on one side… Patrick, on the other hand, took to it like a duck to water. He was a committed racer, liked everything about the P34, and was very good to work with occasionally he’d be a bit.., mercurial, but he was French, after all!

“Patrick was the first driver to test the car, at Silverstone, and his immediate impression was it was very quick. He also said it turned in beautifully if anything, we had to keep a tight rein on him!”

It wasn’t all straightforward, however. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there were problems with the tyres, and also with the front brakes. Because of the construction of the tiny Goodyears, if the carcass were stiffened up, in order to control the profile at high speed, so also was the sidewall. In those days, F1 tyres were still cross-ply – wonderful for spectators, who revelled in the sight of cars sideways, but less so for engineers.

Car had sizeable top speed advantage at Watkins Glen

Grand Prix Photo

“If they’d been radial-ply,” said Gardner “it would have been possible to stiffen the carcass, and not the sidewall to separate them but with cross-plies it wasn’t.

“The first time I saw the car, coming down the straight at Silverstone, I was horrified, because I could see the tyres literally being sucked off the rims. As soon as the driver touched the brakes, they just collapsed down onto the rim. In fact, they never lost pressure it was just one of those hair-raising things, and luckily the drivers couldn’t see it! Later on, we put little windows in the cockpit sides to allow the drivers to see the tyres, to pick up the shadow across them. Whatever Ken may have said, those windows were not put in to allow spectators to see the drivers’ hands at work!