Page 37

Matters of Moment, July 1981

The Farnham Fuss There has been a fine fuss going on in Farnham, Surrey, because the Urban District Council has…

The Farnham Fuss There has been a fine fuss going on in Farnham, Surrey, because the Urban District Council has…

* Only clubs whose secretaries furnished the necessary information prior to the 14th of the preceding month are included in…

Jaguar Drivers Club To celebrate their 25th birthday, the JDC are holding a special anniversary rally at Woburn Abbey on…

Seven different winners from seven races. That hard to believe statistic underlines the competitiveness of this year's European Formula Two…

Acropolis Rally Simple societies of centuries past had simple rules; if you did wrong, you got the club. Civilisation has…

The VSCC Race Meeting at Oulton Park on June 13th had a big attendance (paying spectators 4,000 they said), and…

In the May issue I made reference to Edward Eves of Autocar, telling the story of Henry Royce buying the…

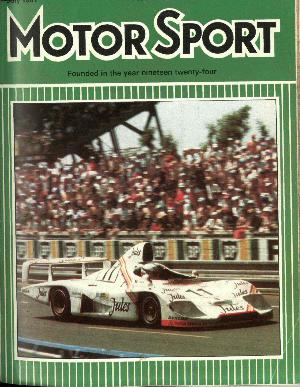

In winning the Le Mans 24 hour race with Derek Bell, Jacky Ickx not only gave Porsche another victory for…

Blydenstein's tiny turbo boosts Astra 1.3 The distinction of the smallest turbocharged engine we have tested now belongs to the…

Due to production schedules, D.S.J.'s reflections and notes on the cars at Monaco appear before the main report of the…

If at first . . . Last month we dealt in some detail with the conception of the Lotus 88,…

Richard Noble's efforts over the last six or seven years will be put to the test in October when he…

The biggest technical interest in the pits was the ingenuity shown in cheating the 6 cm. ground clearance rule: the…

"Racing for Britain"; support for promising young drivers Under the laudable new scheme "Racing for Britain", whereby motor racing enthusiasts…

In April 1976 we published intimate information about the unsuccessful Sunbeam "Silver Bullet" Land Speed Record car and as we…

A Section Devoted To Old-Car Matters A date with Tom Delaney The other day I had a most interesting conversation…

Brooklands had such a large following in its hey-day that it is difficult to appreciate how many people drove there.…

Arab Information Sir, It was with much interest that I read the reference to the Arab cars and particularly the…

It seems that the ridiculously high prices charged for the older vehicles may be on the wane. At a recent…

Aviation for Everyone — then and now The so-called Great War of 1914/18 removed some of the remoteness, if not…

Formula 1 has submitted a tender for standardised gearboxes for 2021, but will teams support the idea? The FIA has opened a tender for gearboxes from the 2021 season onwards as…

Time is running out for Mercedes to find a fix for the porpoising issue that has cost it car performance

The long-running saga of who drives the second Red Bull in 2021 finally came to a conclusion last week with the not-unexpected news that Sergio Perez would be replacing Alex…

They have made the right PC noises since, reaffirmed their commitment to each other, Ferrari, Felipe and Fernando – Alonso would say that, wouldn’t he? – but Massa must know…