Recent Even

Recent Even in Pictures. H. W. PURDY ON THE NEW LAysTALL, IA I, VF,RTAN I NC; A VAUXHALL AT THE EASTER B.A.R.C. MEETING. COMPETITORS AT GREENEORD DIRT TRACK ABOUT TO…

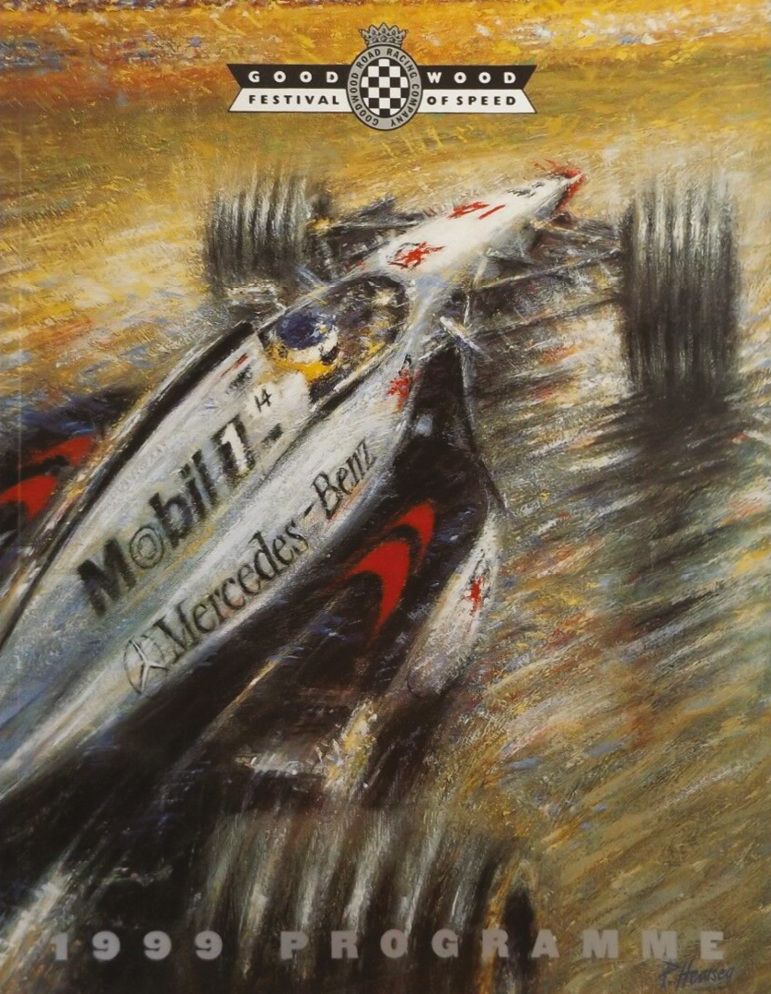

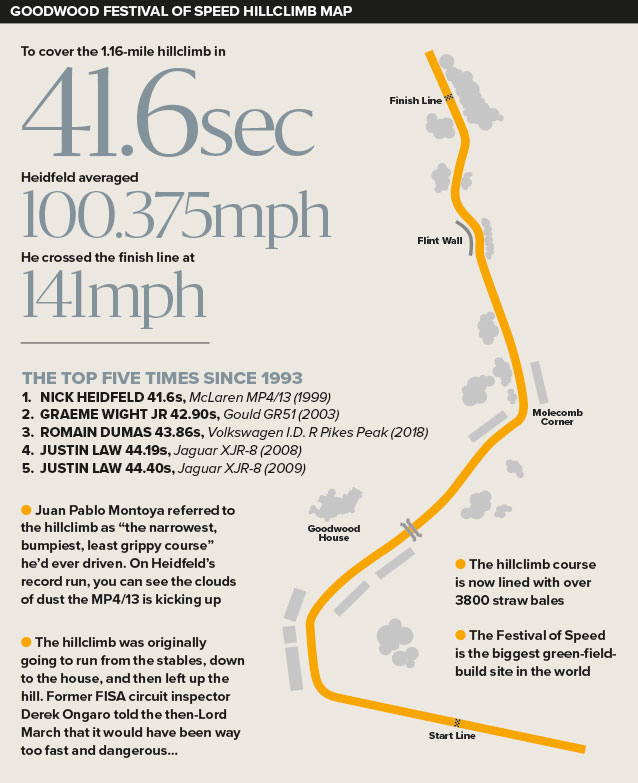

The sun was finally shining down on Goodwood Park after a couple of days of wet weather. The McLaren MP4/13 with a young Nick Heidfeld on board sat with tyre warmers on, ready to climb the 1.16-mile course.

“I was down at the bottom of the Hill with Nick,” remembers former McLaren team principal Martin Whitmarsh, “and I think I was the last one to speak to him. He was young [only 22 years old at the time], trying to make his way into Formula 1, and I remember it distinctly because I did something that was pretty irresponsible. I leant in to speak into his visor and said, ‘look Nick, this is more dangerous than it looks – there’s a crowd, some straw bales, some flint walls, take it easy’. And then, just before he flicked his visor shut, I said, ‘but make sure you don’t get beaten’.”

Seconds later, the marshals pushed him onto the startline, the revs rose on the Mercedes-Benz V10 power plant and the young German disappeared down to the first corner. “As he went round that first corner,” says Whitmarsh, “I remember shuddering, and thinking, ‘what have I done?’”

That 1999 record run is unbeaten, but this summer at the Festival of Speed (July 4- 7) VW is returning to try and take his crown. Having done a 43.86-second run with Romain Dumas at the wheel last year, the team has been away and developed its electric ID R car further.

Goodwood’s now-famous hillclimb traces its roots back to an event organised by the ninth Duke of Richmond, Freddie March, in 1936 for the Lancia Car Club. It was a one-off event, but over 50 years later, the current Duke of Richmond (then the Earl of March) was keen to bring racing back to the circuit, which hadn’t held a motor race since 1966. The Festival of Speed (“I didn’t like the name at the start, it sounded like a drugs party,” admits the Duke) was launched as a tester to see if there was an appetite for motor sport at Goodwood. It was predicted that 2-3000 people would turn up to the first event in 1993, but on the day 25,000 people poured onto the site, many of them not paying, having trampled clean over the fencing. Indeed, there were so many more people than Goodwood had planned for, the team had to find handbags to collect the cash in. These were then unceremoniously dumped in the back of a Ford Granada.

It was still a low-key affair, though, and the sight of modern Formula 1 teams didn’t appear until the second year in 1994. Ron Dennis sent the McLaren-Peugeot MP4/9 with Martin Brundle as the driver and, sure enough, he was fastest up the Hill in 47.80 seconds. “Yes, we did timed runs from the start,” says Whitmarsh. “Inevitably, when you got there in those days, there was a lot of focus from the other cars to beat the F1 car. In the first year it was reasonably relaxed, but we were obviously keen, and the competitiveness came out of us. We had to be quickest. Year on year, that escalated, and it reached that point in 1999…”

Rumours of special gearboxes being built floated around the paddock, but Whitmarsh is adamant that nothing of the sort was done. “We geared it for the event, but it wasn’t a bespoke gearbox. By that stage we were using tyre warmers – it had escalated quite a lot! I remember watching Martin that first year and thinking ‘the problem with bringing racers to a great spectacle is that it’s going to bring the out worst in us’.

“We used to run the car soft for extra traction, and it would have had a Monaco setup with lower gears and maximum downforce. There weren’t parts made specifically for the Goodwood run, they were all from the quiver of componentry you had available anyway.”

Back to the run: The Duke of Richmond was already waiting in the Top Paddock, ready to congratulate the winner of the timed runs, but remembers it well, just from watching it on the big screens. “The lights went green and newoooow. It was electrifying. You knew as soon as you heard those revs that something was going on. He was taking it right up to the rev limit in every gear, it was absolutely screaming. The whole place went quiet.”

“You know,” says Heidfeld, “I don’t remember Martin telling me to get the record just before my run. He did tell me afterwards that he was pretty worried…” Heidfeld had been fastest in 1997 and 1998 with the previous McLarens, but this particular year wasn’t going so well. “The thing that was different in 1999 was that we weren’t the quickest up until that final run. The quickest was Bernd Mayländer in a Mercedes-Benz CLK-GTR. We just wanted to be quickest and at that moment we weren’t, so there was a situation. That was also different for me, because up until that point… That was the only time I thought ‘OK, now I have to beat the other guy and push a bit more, I can’t just go and have some fun’. It was a different mindset for me.”

The MP4/13 was dancing all over the Tarmac from the moment it left the line, and it looked very much on the limit. “Yes,” remembers Goodwood historian Doug Nye, “he was visibly going like hell!” Long-time Goodwood commentator Marcus Pye was down at the startline for the run. “We were very much aware of what we were watching. I guess there was an air of expectation about it. I have stood on that startline for years and the fact that Nick shot away with absolutely no fuss, there were no spinning wheels, we knew: this is business. It was snaking all the way to the first corner; it was snaking all the way past Goodwood House. Near the top of the Hill, I can see it now, it sends shivers down my spine, the revs were stratospheric, and the car was darting around. It was a magnificent run; it couldn’t have been any better. And we’ve seen nothing like it since.”

“It was very emotional, but Nick was pretty calm, typically German”

“It wasn’t totally on the limit,” admits Heidfeld. “The biggest issue that day was that it was the first time it had been dry all weekend. Obviously, you didn’t have many chances to practise, you just went up a few times during the weekend. Being the first dry run, you had no markers, and you didn’t really know where the limit was. You have a bit of memory from the last couple of years, but I couldn’t be totally on the limit. From the inside, it didn’t feel as mad as it looked. It is obvious from the YouTube video that I had to work relatively hard to keep the car in a straight line. But it all felt controlled.”

Heidfeld averaged just over an astonishing 100mph across the resulting 41.6 seconds that it took to get to the top of the Hill. Once past the finish line and in the Top Paddock, he did a 180-degree burnout and calmly got out of the car. “I was there when he jumped out,” says the Duke of Richmond, “and it was very, very exciting and emotional. But Nick was, well, pretty calm, typically German! That run was a fantastic moment, but in some ways it burst the bubble.”

“Afterwards,” says Whitmarsh, “I went to see Charles and just said ‘we can’t do this anymore. We can’t come and pretend we’re not racing if we’re being timed. There’s a competitive spirit in us, that’s why we’re in motor racing. We don’t want to get beaten!” The arms race was progressing at too fast a pace – the teams had tyre warmers on the startline, and young drivers were expected to push harder than they perhaps should have been. From the following year, there was a gentlemen’s agreement that modern Formula 1 cars would no longer do timed runs, and Nick’s record has stayed safe for 20 years. Every year there are requests from hillclimb drivers to come and do a timed run, but Goodwood is proud of the fact that the record is held by a World Championship-winning F1 car. If it is to be beaten, it should be by a suitably special car and driver. Despite Heidfeld saying that he could have gone faster in 1999, 41.6 seconds has been a tough time to beat – even Sébastien Loeb gave it a shot with his Peugeot 208 T16 Pikes Peak car in 2014, but didn’t manage better than 44.6 seconds.

Second-fastest of all time is Graeme Wight Jr in a hillclimb Gould GR51 (42.90 seconds), while at last year’s event, Dumas in Volkswagen’s I.D. R Pikes Peak did the 43.86-second run. Come July 4-7 this year, might Heidfeld’s record finally be broken?

“Having the record is a very special thing for me,” says Heidfeld. “When I did it back in 1999 I never thought we would still be speaking about it over 20 years later! It is always special when people come up to me, all over the world, with a sparkle in their eye and say that they were there in 1999. They remember where they watched from, they remember it so vividly. They really enjoyed it, and that makes me so happy.”

Despite contemporary Formula 1 cars running untimed since 1999, a few drivers have pushed hard when there wasn’t a clock on them. Video footage does show how close they got to Heidfeld’s time, though…