1969 Monaco Grand Prix race report: Hill knocks ‘em for five

Graham Hill is ‘Mr Monaco’ as he takes his fifth win at the principality; Williams’ Piers Courage and Rob Walker’s Jo Siffert round out the podium

Graham Hill, driving for Lotus, on his way to his fifth Monaco Grand Prix win

Motorsport Images

It will be a sad day when the “do-gooders” and “improvers” in our midst cure all the problems surrounding the Monaco Grand Prix the way they have dealt with the Belgian Grand Prix. Racing through the streets of a town should always be part of motor racing, not the whole of it nor the ultimate, but the complete racing driver should be able to drive to the precise limits that street racing demands and cars should be designed to withstand the rigorous test of such a race, just as they should withstand the flat-out blind of the Italian Grand Prix at Monza.

Ever since the Grand Prix round the streets of Monte Carlo was inaugurated in 1929 it has been a classic event, and apart from very minor modifications the circuit has remained unchanged since that day. Suspensions still get compressed as the cars change direction from the horizontal to steep uphill on the fast right-hand bend at Saint Devote; they become light on their wheels as they breast the rise before the Casino square; their swervability is tested severely as they swing left and right across the cambered Casino square in front of the Hotel de Paris; brakes are really pressed hard at the foot of the hill down to the Mirabeau hairpin, and steering lock and an ability to slide the rear wheels out of line are called for at the tight left-hand hairpin where the old station used to be.

Another violent change of vertical direction is experienced at the Portier corner where the cars run on to the seafront road; then it is all acceleration and speed along to the curved tunnel and out into the sunlight again and very fast downhill with the brakes hard on for the chicane. This leads on to the harbour front and along the concrete to the Tobacconists Corner, bouncing over the hump just before it.

Then it is hard left between stone walls, and along the Promenade that is normally forbidden to motor vehicles. At the end it is really heavy braking, and still on a left curve before swinging hard right round the hairpin bend where the Gasometer used to be. Hard acceleration up through the gears and you are past the pits and braking heavily to start Saint Devote corner again. All this in less than 1 min. 30 sec. if you are any sort of Grand Prix driver, and in 1 min. 25 sec. if you are a potential Grand Prix winner.

After the crashes to the two Lotus cars at Barcelona, due, it would seem to failure of the rear aerofoil struts, and the collapse of a Brabham aerofoil almost at the feet of members of the CSI, some drastic action was imminent, and I would have thought the Formula One Constructors Association would have taken some unified action to direct any controlling thoughts that were germinating in the minds of the members of the FIA Sporting Committee.

“Lotus, as only Chapman and his chaps can manage, built up two more Lotus 49 cars to replace the two that were destroyed in Spain”

However, all the Grand Prix contenders arrived at Monaco with full aerodynamic assistance as before, with a few more struts and bracing wires for luck, and even before practice began on Thursday afternoon there was some ominous poking around by members of the organising club on behalf of the FIA Monte Carlo was not its usual radiant self, but it was dry and warm and ideal for some fast motoring and it was not long before there was plenty to be seen.

Team Lotus, as only Chapman and his chaps can manage, had built up two more Lotus 49 cars to replace the two that were virtually totally destroyed in Spain, and they were basically the two cars used in the Tasman races. Hill had 49/10 which had been hastily built “down under” after Rindt had crashed his original Tasman car, and the second one at Monaco was basically 49/8 which Hill had campaigned in the Tasman series.

As Rindt was still on the sick list with head injuries, Attwood took his place in Gold Leaf Team Lotus. The car of Hill had the oil tank mounted over the gearbox, and that of Attwood was to very early specification with the oil tank in the nose. After the wreckage in Spain no-one would have blamed Lotus for giving Monaco a miss, so all credit to them for producing two more cars. Both had full-width rear aerofoils and wide nose fins.

The two immaculate McLarens had aerofoils front and rear, as well as nose fins, and both had the new design of front wheels, now cast in one piece, whereas the prototype wheels in Spain were of riveted construction. Hulme was driving M7A/2, and McLaren was driving the 1969 car, M7C-1.

Brabham and Ickx had as usual the Brabhams BT26-2 and BT26-3 respectively. with nose fins, and two aerofoils, the rear ones having perspex deflectors at each end before practice began, but they were removed before the cars went out.

The Matra International team had two 1969 cars, Stewart driving MS80-02, and Beltoise driving the Spanish GP winning car MS80-01. In addition to their normal complement of aerofoils and movable nose fins they had alternative nose cowlings with aluminium “straighteners” longitudinally on the cowling. They also had their 1968 car as a standby. Naturally all the Lotus, McLaren, Brabham and Matra cars were powered by Cosworth V8 engines and the power was used through Hewland gearboxes.

Enzo Ferrari did not want to get involved with the Monaco GP for various personal reasons, and the entry list left open the actual entrant of the lone Ferrari, letting people assume that Amon was the entrant, but as he had a full complement of staff men from Maranello, it was all a bit pointless. He had two cars to choose from, 0019 as his first choice, and 0017 as a spare, and both had the nose fins moulded into the fibreglass fairing. They were also using the hydraulically-controlled aerofoil on the first car, both cars being powered by the crisp sounding Ferrari V12 engine, without which no Grand Prix meeting is complete.

BRM had three works cars for Surtees and Oliver, and were backed up by Parnell’s earlier car for Rodriguez. Surtees was driving 138-01 fitted with the latest 48-valve engine and BRM gearbox and his spare car also had the new-type engine, but drove through a Hewland gearbox. This car was new and had been built up around the number of the car that Surtees crashed at Brands Hatch, so that on paper it was 138-02. Oliver had as usual 133-01, with 48-valve engine and Hewland gearbox, and all the cars had small pannier fuel tanks along each side of the cockpit, mounted very low. They also all had nose fins and aerofoils back and front.

To complete the entry of 16 cars, there was Siffert with the Walker/Durlacher Lotus 49, Courage with the Frank Williams (Racing Cars) Ltd scintillating Brabham-Cosworth V8, Elford with the Cooper-Maserati V12 of Antique Automobiles Ltd., and Moser with a Brabham-Cosworth V8 that had started life as a 2½-litre special for Courage to race in the Tasman events. Having been built as an 100 mile “sprint car” it had insufficient petrol-carrying capacity, so it was fitted with the two outrigger pannier tanks that McLaren experimented with last year. The little Swiss driver missed the first practice session.

Qualifying

Jackie Stewart put his Matra on pole

Motorsport Images

During last year’s race, Attwood, in his vain pursuit of Hill, set up a new lap record in his BRM of 1min 28.1sec, which was 0.1sec faster than Hill’s best practice time. With a year of progress in engine power and tyre development alone a time of 1min 30sec would have to be a lowly starting point, and the faster drivers anticipated getting well below the existing record, though just how far below nobody was prepared to guess.

“Stewart, Hill, Ickx and Siffert who set the pace, and recorded times that seemed almost unbelievable”

It was Stewart, Hill, Ickx and Siffert who set the pace, and recorded times that seemed almost unbelievable. Stewart’s Matra went sick in its Cosworth engine department so he took the second car, which curtailed Beltoise’s practice, and Siffert caught his left side nose fin on the fence as he braked for the Gasworks hairpin and that stopped his practice abruptly. He had been really braking on the limit, the whole car skittering and juddering as the front wheels nearly kicked, and it was while doing this that he clipped the fence. It spun the car through 180 degrees and ripped off the fibre-glass nose in a shower of bits and pieces, but apart from that, no damage was done; however, he had got down to 1min 26.5sec, which had caused embarrassment to a lot of works drivers.

Another private runner who was excelling was Courage, with the Williams Brabham, and he was only 1sec slower than Siffert and having terrific fun and enjoying himself enormously in some splendid uninhibited fast and furious driving. He said “but don’t tell Frank”, though the owner must have been delighted at the performance.

The new works BRM engines were very flat on initial pick-up and neither Surtees nor Oliver were very happy, while Amon was downright miserable about his Ferrari for it was cutting-out completely on hard acceleration just after he changed gear. When the engine fired again, on full throttle, the jerk was giving him a real pain in the neck. Stewart hit a kerb and broke a rear wheel, which let the tyre deflate, and Surtees put a big kerb mark in a rear wheel rim, though it did no other damage.

The two McLarens were very neat and tidy, and the owner put in some competitive laps without any drama or fireworks. In spite of having a hurriedly-built car, Hill was in great form and trying hard, being second fastest overall, but Attwood was learning his way along, not having driven a Lotus 49 before.

It was Stewart who really made things hum, and he got down to an incredible time of 1min 24.9sec, the Matra accelerating away from the Gasworks hairpin like a dragster. The podgy little Matra MS80 looks almost as wide in the track as it does long in the wheelbase, the tiny 13” low-profile Dunlop tyres adding to this effect. Atmospheric conditions being good some fast laps were expected, but over three seconds off the lap record was quite fantastic, and on the first day of practice as well.

Before practice finished officialdom was already “clucking” and “ticking” about aerofoils, though why this wasn’t done immediately after Barcelona no-one knows. Presumably the CSI were hoping that aerofoils would quietly disappear from whence they came, and save anyone making a decision. After practice there were various meetings and discussions, the first approach being to formulate some sort of limitation on size and construction, but eventually it was agreed, not unanimously, that aerofoils that were not part of the bodywork would no longer be permitted.

McLaren and Ferrari were pleased to call a halt to aerofoil development, though everyone felt that the decision should have been made before practice began. In consequence of the CSI decision the times recorded on Thursday were cancelled and practice began all over again at 8:15am on Friday morning, all the cars running “naked” except for nose fins, and deflectors on the engine covers on McLaren’s own car and Amon’s Ferrari. The ignition system had been changed on the BRM engine in the Surtees car, but it still was not competitive, though it was better, and Amon was having the same fuel system trouble on the spare Ferrari as he experienced yesterday.

Siffert’s car had been patched up with layers of fibreglass but before he got very far the Cosworth engine blew up and that was the end of his practice. With the short time available between the decision to abandon separate aerofoils and the second practice session no-one could do much about suspension settings and most of the cars looked a bit unstable under heavy braking and were wandering a bit on hard acceleration out, of the Tobacconist’s Corner, but it was only a question of re-adjusting everything to unloaded suspensions.

There was minimal difference in lap times and everyone seemed to be getting on with the job and learning all over again about anti-roll bars, spring rates and shock-absorber settings, things they seemed to have forgotten about since the inception of aerodynamic assistance.

It was still Stewart who set the pace, back in his own car, but Hill was right behind him, and Ickx, Brabham and Courage were not far away. The Parnell BRM was still using an old 1968 engine, so Rodriguez had little hope of keeping up, and all Elford could do with the old Cooper-Maserati was hope to go fast enough not to get in the way. The scavenge oil pump stopped working on Oliver’s car and he ground to a stop in a cloud of smoke when the crankcase filled with oil, and Ickx had to walk back through the tunnel when a rear hub carrier broke on his Brabham. As the chequered flag ended practice Beltoise came in slowly with a broken drive shaft, and the hurly-burly of street racing was beginning to take its toll.

The final practice was on Saturday afternoon, after two Formula Three Heats had been run, and there was plenty of time to make good damage or make modifications. Siffert’s car was fitted with the team’s 1968 engine, Surtees had the engine changed in his BRM to try and improve things, and the number one Ferrari had a small petrol header-tank mounted above the engine to try and cure its problems.

Conditions were still not typical Monte Carlo, but were ideal for fast driving, with dry roads and no glare. Having thrown away all aerodynamic devices there was nothing left but to return to suspension adjustments, and many mechanics found that they had forgotten which spanner to use for anti-roll bar adjustment, or shock-absorber adjustment.

As the afternoon session went on everyone got back into the old pre-aerofoil groove and there was some very fast and furious motoring. Even though there was no question of anyone having to qualify the pace got more and more furious, and at one point you would have thought the race had started for everyone seemed to be driving right on the limit and the pace was ridiculous. It was one of those unpredictable occasions when something sparked off a burst of enthusiasm and onlookers began to say “Wait a minute, the race is tomorrow, not today”.

Stewart got down to a shattering 1min 24.6sec, Beltoise was less than a second slower, the Ferrari went properly for a brief moment, and Amon recorded 1min 25.0sec. Hill stuck at 1min 25.8sec, Surtees had a good go with the BRM and did 1min 26.0sec, a time which Siffert equalled, even though he was using a 1968 engine.

The pace in midfield was really competitive, as can be judged by McLaren and Hulme doing 1min 26.7sec and 1min 26.8sec, respectively, well under the existing lap record, and yet being on the sixth row of the grid. The first 12 cars were all well within the existing lap record and the price paid for this mad thrash, that was unpremeditated, was that the Ferrari broke its differential and Brabham and Ickx broke drive-shafts within sight of each other. Stewart’s time of 1min 24.6sec compared with the existing record of 1min 28.1sec was really stupifying. The ravages of the final practice session were not as bad as they might have been, and with the race starting at 3pm on Sunday there was adequate time to get everything set up for the race.

Race

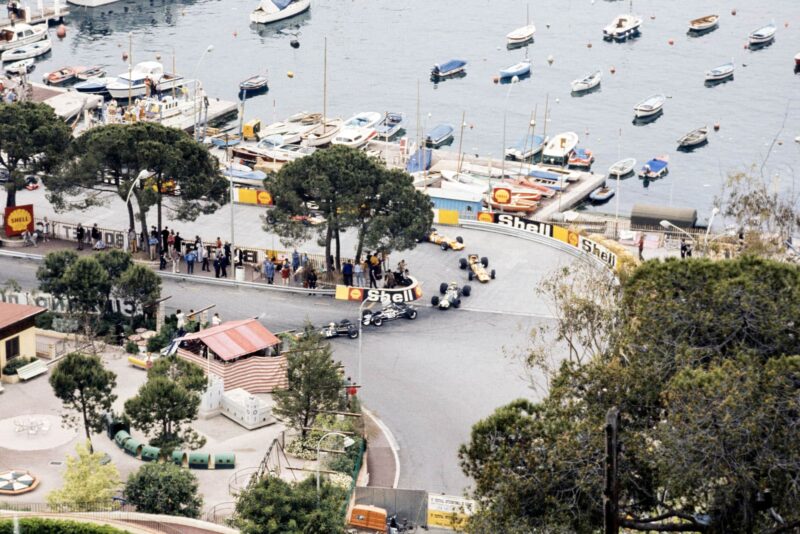

The field threads through the Gasworks Hairpin at the start

Motorsport Images

Once again the sun refused to break through the overcast, though the air was warm, and after Prince Rainier had opened the circuit by driving round in a Lamborghini Espada, followed closely by an orange Lamborghini Miura, the cars lined up for the start, which was given by Paul Frere, the new Race Director. It was interesting that the two works Brabhams were side-by-side in row 4, and the two works McLarens were side-by-side in row 6.

Hulme was feeling far from well, suffering from some sort of influenza bug, and could not concentrate for very long. Hill’s Lotus had a deflector plate fitted over the rear end of the car, McLaren’s car had an engine cover with a built-in spoiler at the end, as did Amon’s Ferrari.

“There was some bumping and boring among the cars at the end of the field, and Oliver ended up on the side of the road with a bent front suspension”

The two works BRM cars had pannier fuel tanks and Oliver had nose fins on his car. It was a good clean start, but just round the first corner there was some bumping and boring among the cars at the end of the field, and Oliver ended up on the side of the road with a bent front suspension on his BRM.

In no time at all Siffert and Amon left the rest of the field behind, and though Beltoise led them for two laps Hill was soon by into third place. Ickx and Courage got past Siffert on the fourth lap and the Lotus of the Swiss sounded a bit flat.

In only five laps Stewart was leaving the Ferrari behind and running away from everyone, completely unchallenged, while Amon was also leaving the rest behind. Hill, Beltoise, Ickx and Courage were nose-to-tail and Siffert was keeping ahead of Surtees, Brabham, McLaren, Attwood and Hulme. At the end came Rodriguez and Moser, followed by Elford in the old Cooper-Maserati.

Apart from the group racing for third place all serious competition had fizzled out, Stewart was dominating everyone in a masterly and easy fashion, and Amon was on his own in second place.

On lap 10 Brabham was following Surtees along the sea front, approaching the tunnel, and had just decided to pass the BRM on the right when the Bourne car had its gearbox go wrong and virtually stopped abruptly. The two cars collided, the left rear wheel and hub carrier being torn off the Brabham, the right front suspension of the BRM being creased, and the two cars flew apart.

The BRM skated to a stop on the left of the road close to the seawall with its front wheels pointing in all directions, about 100 yards from the tunnel, the errant Brabham wheel, hub and brake unit landed at the entrance to the tunnel, and the Brabham skated through the tunnel on three wheels and with no brakes, out the other end, and stopped on the right hand side of the road about 100 yards after the tunnel exit. It was all so impossible, yet miraculous, that Brabham actually laughed about it, and both drivers walked back to the pits.

The blast through the tunnel provides a unique challenge in Grand Prix racing

Motorsport Images

By this time Stewart had 9sec lead over Amon, and at Monaco that is an unassailable lead. Behind these two Beltoise was hanging on grimly to Hill, but just behind them lckx and Courage were really getting worked up. Already Elford, Rodriguez and Moser had been lapped, but on lap 16 the little Swiss coasted his orange Brabham into the pits with a broken universal joint in a drive-shaft, and on the very same lap Rodriguez disappeared when his BRM engine suddenly died on him.

Just as the Tyrrell pit signalled to Stewart to switch off the auxiliary oil scavenge pump, which they use in the opening laps to make sure the crankcase is scavenged properly, Amon disappeared when the Ferrari differential broke, so that now Stewart really had nothing to worry about. On lap 19 Tyrrell signalled the little Scot to use no more than 8,500rpm, instead of well over 9,500rpm, and Stewart had time to pick his way round some of the more severe bumps and drive to give the car an easy time.

“Ickx and Courage were very evenly matched and having a real go, running in the classic American speedway style of wheel-to-wheel, and hub-to-hub”

Only 20 laps had gone and the race as such was all over, as far as the lead was concerned, but Beltoise was still hounding the number one Lotus, though he was not making much impression. With Ickx and Courage it was a different story, for they were very evenly matched and having a real go, running in the classic American speedway style of “wheel-to-wheel, and hub-to-hub,”. As Beltoise passed the pits at the end of lap 21 there was a bang from the Matra and a drive-shaft broke and the Frenchman coasted out of sight.

On the very same lap the Matra could not believe their eyes for Stewart failed to appear, and his car had also broken a drive-shaft, just like that, when he was taking it easy and not straining anything. This meant that Hill found himself in the lead and Ickx and Courage were now racing for second place, which was a lot more serious than racing for fourth place, as they had started out. As they finished lap 27 Ickx had a gear-change go wrong, and as the car hesitated Courage was past, but the young Belgian soon recovered himself.

Wearing an all-enveloping American crash helmet, Hill was only recognisable by the white stripes on it, and Ickx was similarly covered up, only his racing number distinguishing him, but Courage could be seen to be gritting his teeth and working really hard to keep the private Brabham of Williams in front of the works Brabham.

At half-distance, or 40 laps, Hill had a very comfortable 20sec lead, but second place was still wide open, even though Ickx had got in front again on lap 32. These two young lads were putting on a splendid show, driving right on their limits and giving nothing away to each other. A hopeful flag marshal at the Gasworks hairpin kept showing Ickx a blue flag, but he was wasting his time, neither of them were giving an inch and neither of them expected it. It was first-class racing. They were 34sec ahead of Siffert in the flat-sounding Walker Lotus, who was keeping ahead of McLaren, but Attwood was finding his feet in the works Lotus and slowly creeping up on them.

The very off-colour Hulme was already lapped, and Elford had been lapped twice, and that was all that was left of the 16 starters. Hill seldom puts a foot wrong on the Monte Carlo Circuit, as his four previous victories have proved, and the 27th Monaco GP was no exception. He was lapping at a very comfortable 1min 27sec to 1min 28sec and continually increasing his lead, so that by lap 50 it was 23sec.

Hill waves to the crowd after sealing victory

Motorsport Images

On lap 49 as Ickx led Courage along the sea front, before the tunnel, the left rear suspension and hub carrier casting broke and the car lurched across the road in front of Courage and ended up on the footpath, the young Belgian boy being unscathed, and the car was virtually undamaged apart from the breakage.

It was now all over, Courage could relax a little, Hill could ease off, merely maintaining a comfortable lead, and Siffert was safely in third place. Behind the Swiss it was not so secure, and Attwood was relentlessly closing on McLaren, not always a measurable amount on each lap, but getting closer as the race progressed.

The Lotus finally caught the McLaren on lap 59, and moved up into fourth place, but it was still 18 sec. behind the Walker/Durlacher Lotus. Although the gap fluctuated on some laps it never really showed signs of diminishing and the order remained unchanged to the end of the 80 laps, the only change in the situations being that Hill lapped McLaren on lap 71. For the second year running Hill has driven a very unlikely winner, yet kept it going to win, this one making his fifth Monaco victory.—D. S. J.

Monaco Mutters

- The driving of Ickx and Courage was a joy to watch, they were really having fun. Stewart’s driving is so smooth and effortless that he makes everyone else look like beginners.

- Monte Carlo is not Oliver’s circuit. Last year he crashed before the end of the first lap, this year, after the first corner.

- Aerofoils or Gimmicks. Could it be that everyone has been working up a blind alley for nearly a year? Superchargers were outlawed, alcohol fuel was outlawed, streamlined bodywork was outlawed, and now aerodynamic assistance is outlawed. There won’t be much progressive thought left in Grand Prix racing soon.

Monaco Formula Three

Run on Saturday with two Heats before Formula One practice and the 24-lap Final afterwards, the two Swedish drivers Peterson and Wisell had a very good scrap that lasted until just before the end, when Wisell shot up the escape road at the chicane. Engine trouble in Heat 1 put Jaussaud too far back on the grid for the Final to be in contention, and Dubler was forced out in Heat 2 with engine trouble when he had a commanding lead.