Castellotti and Musso, both abnormally brave, were killed in Enzo’s cars, and thereafter he was predisposed to look outside Italy. “He was getting criticised to hell in the press,” said Phil Hill, “and of course the Vatican pitched in, saying racing should be banned, Ferrari was a killer of young men, and all that stuff…”

That being so, the Old Man decided against more homegrown drivers, but at the same time – as often with this unpredictable man – that put him into conflict with himself, for in his heart what he wanted most to see was Italians winning for Ferrari.

There followed a classic Maranello fudge. For 1961 the factory F1 drivers were Hill, Wolfgang von Trips and Richie Ginther, but Eugenio Dragoni (later a controversial Ferrari team manager, but then operating the small Scuderia Sant-Ambroeus) reached agreement to enter a fourth car occasionally for a promising Italian.

“It was my first big race. Was I nervous? Of course! Stirling Moss was in it”

Lorenzo Bandini, another star of Formula Junior, seemed the logical choice, but eventually Baghetti got the nod. Predictably, the Italian press tried to stir a rivalry between them, but to no avail. “I was surprised to be chosen because he was better than me,” said Giancarlo, “but we always got along well – no one could ever be an enemy of Lorenzo.”

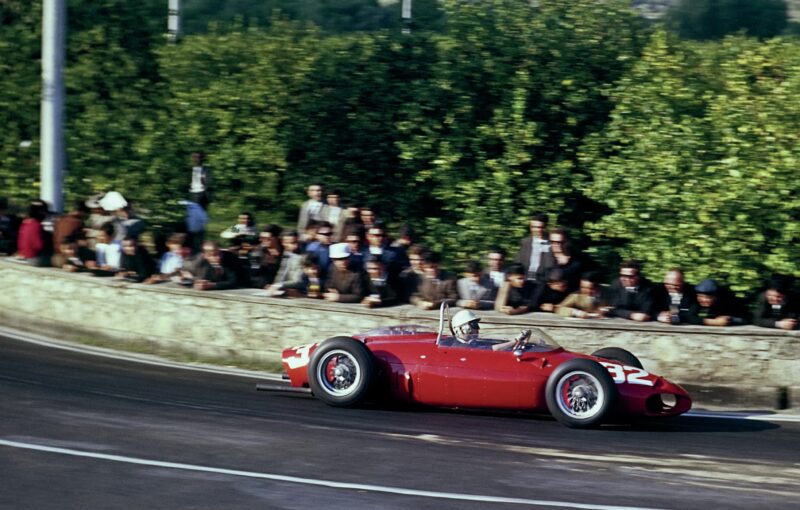

In April 1961 both went to the grid at Syracuse, Sicily’s wonderful open-road circuit, Bandini in an elderly Cooper-Maserati, Baghetti making his F1 debut in the ‘private’ Ferrari. As Maranello’s only representative, he qualified second, a tenth away from Dan Gurney’s Porsche, and if few outside Italy had heard of him, after the race his name meant rather more: he won it.

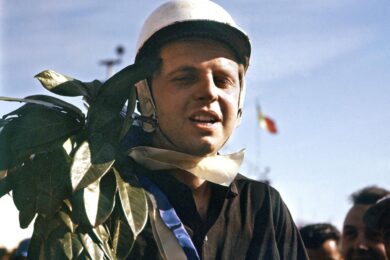

Debut victory at Syracuse, beating Gurney’s Porsche

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

“It was my first big race,” said Giancarlo, “and was I nervous? Yes, of course – Stirling Moss was in it! I knew in practice that I had more power, but it was all new to me, and Gurney was never far away. I just tried not to make mistakes –I remember one big slide, when I nearly hit the wall, but that was all. They carried me up on their shoulders afterwards… it was hard to believe I had won.”

Baghetti’s car was actually the first rear-engined Ferrari, which had made its debut at Monaco the year before, driven by Ginther. In 2.5-litre form, it never raced again, and by midseason had metamorphosed into a svelte F2 car, which took von Trips to a conclusive victory at Solitude.