I had a good look over it, and sat in it. Somebody even fired it up one day. There were no electronics, it was all mechanical. I don’t know quite what the procedure was to get the turbine going, but I think you had to heat it up and there was some sort of starter. It was just like lighting a big blowlamp.

I liked its simplicity. Although it was four-wheel drive with a turbine, when I looked at it I thought, ‘It doesn’t look massively complicated’. And I always think that’s a good thing, when a design looks simple enough that you could just sit there and do it in five minutes. It gave me that impression.

It was quite a clean car, with a very pronounced wedge shape and a chopped-off tail. Without the radiators and all the rest, it was very tidy. It must have been reasonably good aerodynamically. The suspension was good because the uprights and wishbones were the same all round, although obviously only the front wheels steered. It was all neatly done.

Like the four-wheel drive system, the turbine engine didn’t look overly complicated. You’d expect pipes and wires everywhere, but it wasn’t like that at all. When you stripped the gubbins off the turbine engine, it was just this little device. It was very well executed.

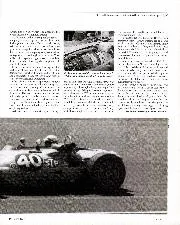

Hill and Leonard lead the way at the start

Getty Images

For a race like Indy, turbine power was perfect: you could produce a lot of horsepower in a relatively compact package; it was better suited to an oval, where you have a lap of fairly constant speeds; it was all fairly progressive and repetitive. I think it was pretty efficient fuel-wise, too, and probably made the most of the pitstop strategy.

Looking at the spec sheet, the engine weight of 2601bs was producing 500bhp when running on gasoline. I guess it was a pretty good power-to-weight ratio in those days. It didn’t really have a gearbox – it basically just powered to the wheels. I think that’s what was so wonderful about it, and made it a lot simpler inside. The weight distribution of 43:57 was pretty much the same as today.