Meanwhile, a new Road Traffic Bill was on its way through the House of Lords. Although the bill dealt primarily with mundane matters of safety and vehicle regulation, Lord Brabazon — himself a former racing driver, winner of the 1907 Circuit des Ardennes on a Minerva — stood up to propose an Amendment to the Bill which would give the Minister of Transport powers to sanction the closure of public roads, where and when appropriate, for the purposes of motor racing. “Here in Great Britain,” quoth his lordship, “we have the second-largest motor industry in the world. In motor racing, Jaguar have developed disc brakes and Mercedes-Benz have developed fuel injection. We may even, in the future, see such innovations on everyday road cars. The Government should be prepared to do something to help this great industry, which has pulled us out of so many difficulties through the lean times. There might be clamour against closing the roads, but it would only be for two or three days in a year. Recently, on a main road travelling north, I was held up for 45 minutes by the Quorn Hunt, and nobody said anything at all in expostulation.”

Lord Howe, 1931 Le Mans winner and president of the BRDC, spoke in eloquent support of the value of motor sport and the huge draw of road races on the continent of Europe. The Amendment was also backed by Lord Teynham, the chairman of the AA, and by Lord Strathcarron, himself a keen amateur racer. Only one backbench peer, Lord Moyne, spoke against it, grumbling that when racing took place near his house in Ireland “the quiet of the countryside was spoiled by a fearful and appalling noise that can be heard for many miles.” Ironically Lord Moyne’s first wife, Diana Mitford, later married Oswald Mosley, and their son Max went on to play a not inconsiderable role in the organisation of international motor sport.

Stovebolt would have been eligible for event, so made perfect recce machine

Matthew Howell

But the Paymaster-General, Lord Selkirk, told the debate that the correct procedure for closure of public roads for a motor-racing event would be by way of a Private Bill. “If due provisions are made for the public to be properly safeguarded and local traffic is reasonably undisturbed, it might well find Parliamentary approval. I will readily give an assurance that the Ministry would not automatically oppose such a Private Bill.” Given this assurance, Brabazon withdrew his Amendment.

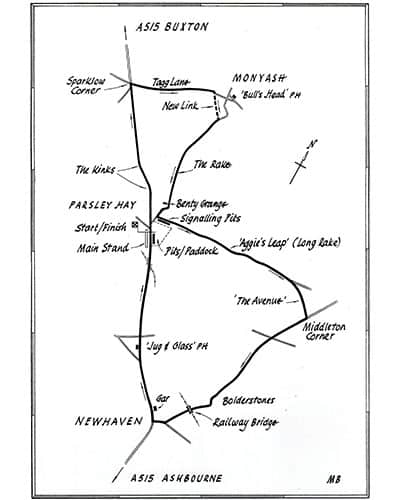

This all sounded most encouraging. But by the time the Lords again debated the matter three months later, the world had changed. Six weeks before, during the Le Mans 24 Hours, Lance Macklin’s Austin Healey 100S swerved to avoid Mike Hawthorn’s pitting Jaguar D-type, and Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes 300SLR ran up the back of the Healey and was catapulted into a crowded spectator enclosure. In all 84 people died, and over 120 were injured. Lurid newspaper headlines around the world called for all motor racing to be banned forthwith. In Switzerland that was actually done, while it was suspended in France and elsewhere. In the second debate Lord Howe did his best to support the Parsley Hay proposal, but it was almost universally opposed, most speakers now agreeing that the proper place for a motor-race was on a private track. Several of their lordships displayed little understanding of motor sport: in the patronising view of one, “all cars that race are prototypes, and all the technical experience gained makes not one jot of difference to the modest little motorcar that is bought by a Bill Jones or a Peter Robinson.”

In theory there was still nothing to stop the Derbyshire County Council presenting a Private Bill, but two months later came another tragedy, this time on a track very close in character to the Peak District proposal. The Dundrod circuit in Northern Ireland, on 7.4 miles of fast, narrow country roads outside Belfast, was once again the scene of the Tourist Trophy, a World Sports Car Championship round that attracted all the top teams. Unwisely, the organisers had accepted an entry from an inexperienced French amateur, Vicomte Henri de Barry, in an apparently standard pale blue Mercedes 300SL coupé. He was quick on the straights but slow through the corners, and right from the start a queue of smaller-capacity cars with more expert drivers built up behind him.