An MV cut-back sparked John’s four-wheeled conversion, first testing the water with Vanwall, then racing Cooper, then Lotus, soaring FJ-F2-F1 within 1960. On the rebound post-Ferrari ’66 he joined Cooper-Maserati, rather like Lewis Hamilton jumping to Williams mid-year, and the fire he put under them forged Mexican GP victory by season’s end. For John, having enabled Maserati to humble Ferrari was just delicious! In contrast, at his Team Surtees works at Edenbridge in 1970 I asked him about the Chaparral he had been driving in the Can-Am Championship. Talk about a straight answer: “That Chaparral was without doubt the worst racing car I have ever had the displeasure of sitting in.” His 1969 BRMs were “not just appalling, but unsafe too” – and he told me why he had walked out of Ferrari in mid-1966, something upon which we shook hands not to confide in his lifetime. “It finally became a shouting match with Dragoni – and a bit with Forghieri too – and then Dragoni said that if I insisted on finishing my season with Ferrari, they could no longer guarantee my safety in the cars. I could only read that as a threat.”

His wins for Ferrari included the Nürburgring 1000Kms (twice), the Syracuse GP (twice), the German GP (twice), the Italian GP, the Sebring 12 Hours and the Monza 1000Kms, in the rain, despite failed screen wipers. Never forget that he drove again for Ferrari, in the 1970 512S endurance cars. Mr Ferrari – who habitually addressed him as ‘Giovanni’ had always kept the door open – he loved his motorcyclists, like Nuvolari, Varzi, Taruffi and so many more. And of course John was Mr Lola T70 – developing the open Can-Am roadster and the closed T70GT with Eric Broadley. John shone in British Group 7 racing, won at St Jovite, Riverside and Las Vegas to become the first Can-Am Champion, and later developed and engineered his own Surtees Formula A/5000, F2 and, from 1970, F1 cars.

Surtees in the Ferrari T-car at Monza, 1964

Grand Prix Photo

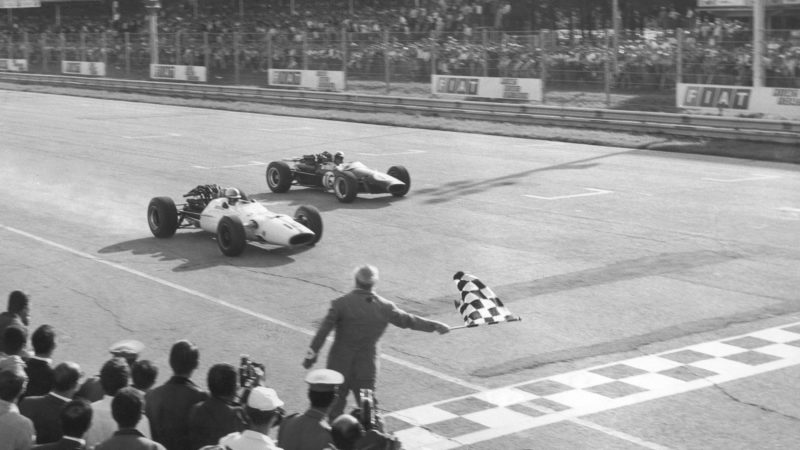

But his exploits 50 years ago in the slimline 1967 Lola T100 – his 1600cc Formula 2 car – really shone. On consecutive weekends he won at Mallory Park then at Zolder in Belgium – first running rings around young upstart Jacky Ickx’s Tyrrell-Matra in pouring Leicestershire rain. So who was the rainmaster that weekend? In a two-heat race at Zolder John, Jim Clark, Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Jack Brabham all locked into a bare-knuckle street fight. The last five laps of the second heat remain an almost-forgotten classic…