European Touring Car Championship, round one

Brands Hatch, March 18th. The opening round of the European Touring Car Championship at Brands Hatch on March 19th proved one thing at least. Even though the series had diminished…

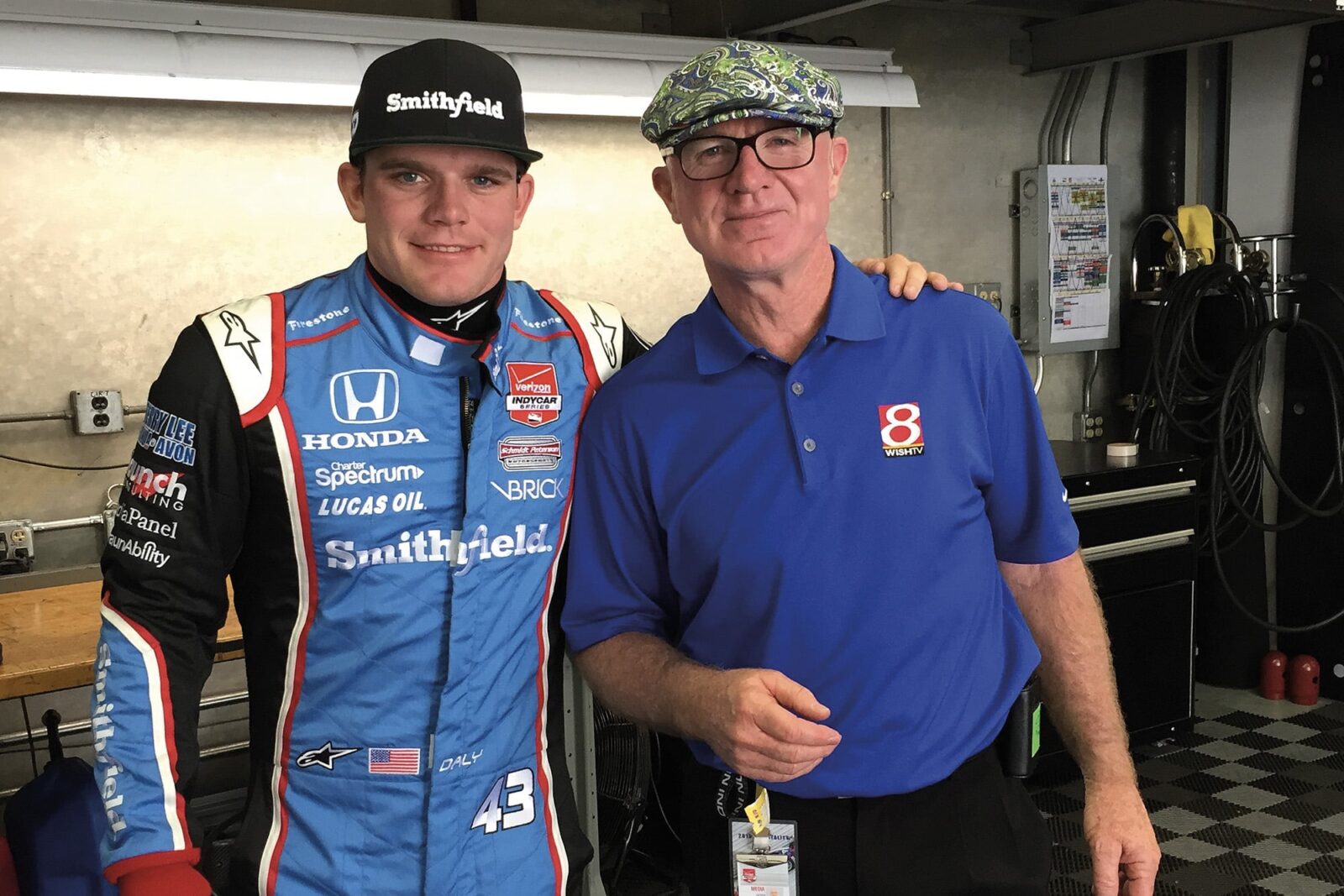

Conor has a chance to crack IndyCar, but Derek made it to F1

Derek and Conor Daly both had to scrap their way through the lower formulas to reach their goal of Formula 1. While father Derek reached the summit, racing for Williams, Ensign and Tyrrell among others for a total of 64 World Championship races, Conor fell short at the GP2 level. But Derek’s experience and management of Conor’s career meant the younger Daly made it to the Indianapolis 500 and has had a stop-start IndyCar career since. Now, Conor is one of the more popular drivers in the American series, and the differences between the two Dalys’ approach to racing couldn’t be starker.

Derek Daly: “Our upbringing and lifestyle couldn’t have been more different. I lived in Ballinteer on the southern outskirts of Dublin, where my father owned Daly’s grocery store. We kept chickens in the back yard, and it wouldn’t be unusual to walk into the kitchen and there’d be Dad, chopping the head off a chicken and plucking it for Sunday dinner.

It was fairly basic. Dad’s only mission was to provide for his family. It was blue-collar, do the best you can. If I wanted a motorbike, when I was 16, I had to work and save money. When I bought my first car, an NSU Prinz, I had to do the same.

There was no motor sport in our lives, and certainly no interest on my father’s part. But one day, when I was 12, I was coming back from school and there was a truck with Sidney Taylor Racing on the side. I tell Dad, and it turns out he knows all about it, Sidney’s sister is a customer. He says: ‘At seven o’clock tonight I’ll take you to see the car’. Off we go.

The next day, he takes me to Dunboyne, where there was a road race. Also in that race was Mo Nunn, who’d go on to establish Ensign. We sat on the grass banks and watched the cars. I remember the colours, the noises, the smells. That was the day I was hooked: ‘I’m going to be a racing driver,’ I told myself.

Conor was born in America into a racing family. As a baby, he’d be dropped at the Racing Babies crèche while I went to stand in front of TV cameras, reporting on the Indy 500 and other races. It was a very different start, but just because he had a father with connections doesn’t mean he didn’t have to work hard. As Al Unser Jr once said: ‘Yes, my Dad opened doors for me, but I always had to walk through the doors myself.’

The ’79 Ensign in South Africa

Grand Prix Photo

I believe that’s so true because, in our sport, you can’t hide anything. Any weakness becomes evident as our sport makes such demands, physically, emotionally and intellectually of drivers.

As he grew up, Conor never knew me as a racing driver, only a media person. Somebody had to tell him I was once a driver, so I don’t think it was awkward. He looks like a Daly, and walks and runs like me, which is awkward, but his temperament is the complete opposite of mine. I was a Type A personality; aggressively go-do-it, make your list, get your notes, get it done, follow through. He’s the opposite. He’s laid-back, placid, easy-going.

When he made the transition into racing cars, I think he was 14 or 15, I told him: ‘I’ll help you in every way I can, but you have to pull me through the sport. I’m not going to pull you through it. I don’t need to live through you. It’s too dangerous, too expensive, too big of a time and lifestyle commitment. So, as long as you’re pulling me, I’ll help you in every possible way.’ I went on to manage him, handle his deals, coach him and keep him on the straight and narrow.

“Dad found a sponsor for the Indy 500, then the car burned to the ground!”

At the start of my career, I did things by the seat of my pants. I part-exchanged a Ford Anglia and £400 for an old Lotus 61 Formula Ford, bought from Eddie Jordan. Then David Kennedy and I decided we needed to race in England if we were going to make it. We needed new cars fast, which needed lots of money. We booked tickets to Australia, discounting work at the Keystone oil pipeline in Alaska, because it was too cold and needed expensive specialist clothing, and worked down the iron ore mines. We made a small fortune.

Once home, I won the 1975 Irish Formula Ford championship, then bought an old bus and converted it into a race car transporter to live in. Mum made the curtains and Dad made the mattress, friends helped fit wooden seating and doors. Then I went to England.

Eventually, the lorry broke down outside the Hawke factory in Southend, so I lived in it in the car park! After winning Formula Ford in 1976, including the Festival at Brands Hatch, I left the lorry and hiked back to Dublin. I have no idea what happened to it.

It paid off, as Derek McMahon called me and offered a drive in Formula 3 for 1977. To give you an idea of times back then, at the first F3 test at Thruxton, I didn’t even have a mechanic. There was just the car in a Commer van and me, yet I won the championship. It was just ahead of the time when you had a fleet of engineers, spare parts and so on. About 13 months after winning the Festival, I got my first test with the Theodore Formula 1 team.

I don’t think I had enough comprehension of the engineering to set-up a racing car, which ultimately meant in F1 I drove on instinct and reflex. If I wasn’t going fast enough, I drove harder. Looking back, I’d have preferred a year in Formula 2 to learn the ropes before going to F1.

But Conor has the ability and tenacity. I compare him with Nigel Mansell. Mansell had the talent, the grit and the mental skills, even when people said he was no good. As soon as Mansell won, he won a slew of races. To me, he’s a stand-out World Champion because of how he did it.”

Conor Daly “Dad wasn’t the only competitive person at home. Mum [Beth] was quite the competitor. She raced jet skis at World Championship level around the time I was a baby, and she would feed me between heats and races. One way or another, I’d be at races with Mum or Dad. It was a big part of our lives.

She knew that the cars were safer than in Dad’s day, so she wasn’t overly concerned about me going racing in that respect. Yet in terms of career prospects and long-term stability, Mum knew it would be difficult. There are seven billion people in the world, and only 20 get to race in Formula 1 and 33 compete at the Indy 500. So she’s super-supportive and, like all good mums, she’s my biggest fan.

Dad was tough on me but never forced me to race. We went to the kart track because my neighbour wanted to go, I thought I’d tag along and try it. I had to show that I was prepared to do whatever it took to be the best I could be. I was reading go-kart set-up books when I was 13 or 14, through to early high school.

Conor Daly on the way to finishing 12th at Toronto during the 2015 IndyCar season

Getty

My path to racing was helped by the buzz I was creating in karts. That’s what people want to see, and Dad was then able to get out there and make approaches, which brought on board the likes of Greg Pickett, of Muscle Milk, and Jerry Forsythe, the Indy and Champ Car team owner. But it was a small sum we had to find when I started in the Skip Barber series. I was able to win it in my first year, which meant I could be self-funding thanks to a $350,000 scholarship.

That was a launchpad. Dad was my rock. He was the guy I would go to with questions about driving, the one that would organise travel and logistics, help with sponsors. I figured all I had to do was focus on racing.

That’s how things played out when we went to Europe in 2011. We had won everything we needed to win in America, and the next step was IndyCar or F1. Dad said it was now or never, and spoke to the right people at the right time and came up with an option on an F1 contract with Force India. All I had to do was prove myself in GP3 [F3].

In 2013, I was in contention for the championship with two races to run. I had to win the title to keep my funding and support from Force India but at Monza, in the first race, a car [driven by ART GP team-mate Dino Zamparelli] lost control and took me out. It meant Daniil Kyvyat won the championship. At that point, everything I had in Europe had gone, and it was a tough time.

I thought I could have won that series and wanted to prove a point to people, so in 2014 I managed half a GP2 season, but I was aware that my European career was over and I started handling my affairs.

I’d done the Indy 500 in 2013, and that had been such a great year, up until the downer of the crash. But I’d kept in touch with a lot of people, and by 2015, I fully committed to the US race scene, and Dad managed to find a sponsor for the Indy 500. Then the car burned to the ground before we could race! Sam Schmidt felt bad and had me substitute for James Hinchcliffe, creating enough of a buzz to get me a full IndyCar rookie year in 2016.

This year, I’m grateful for the stability that comes with my partners: the US Air Force and Ed Carpenter Racing. The team has the core group of people that it started with, and they’ve been so fast – Ed has a ton of poles – and they’ve won races on road courses and ovals. I like the engineering group and I really can’t wait to get racing.

I’d never drive the cars of Dad’s era, though. I’ll be forever thankful to him for all his support, but when I look at those old cars I feel sick. I find it funny that the previous generation says that the sport doesn’t do enough for fans. I am always thinking of my ‘brand’, appearing on The Amazing Race, and I like to fire up my Xbox and game against anyone out there, usually on Call of Duty or Forza 7. If you fancy your chances against me, my gamer tag is @connordaly22.

Follow James on Twitter @squarejames