Ford GT40: Ferrari beater

The Ford GT40 was built to humble Ferrari at Le Mans. Which it did – eventually

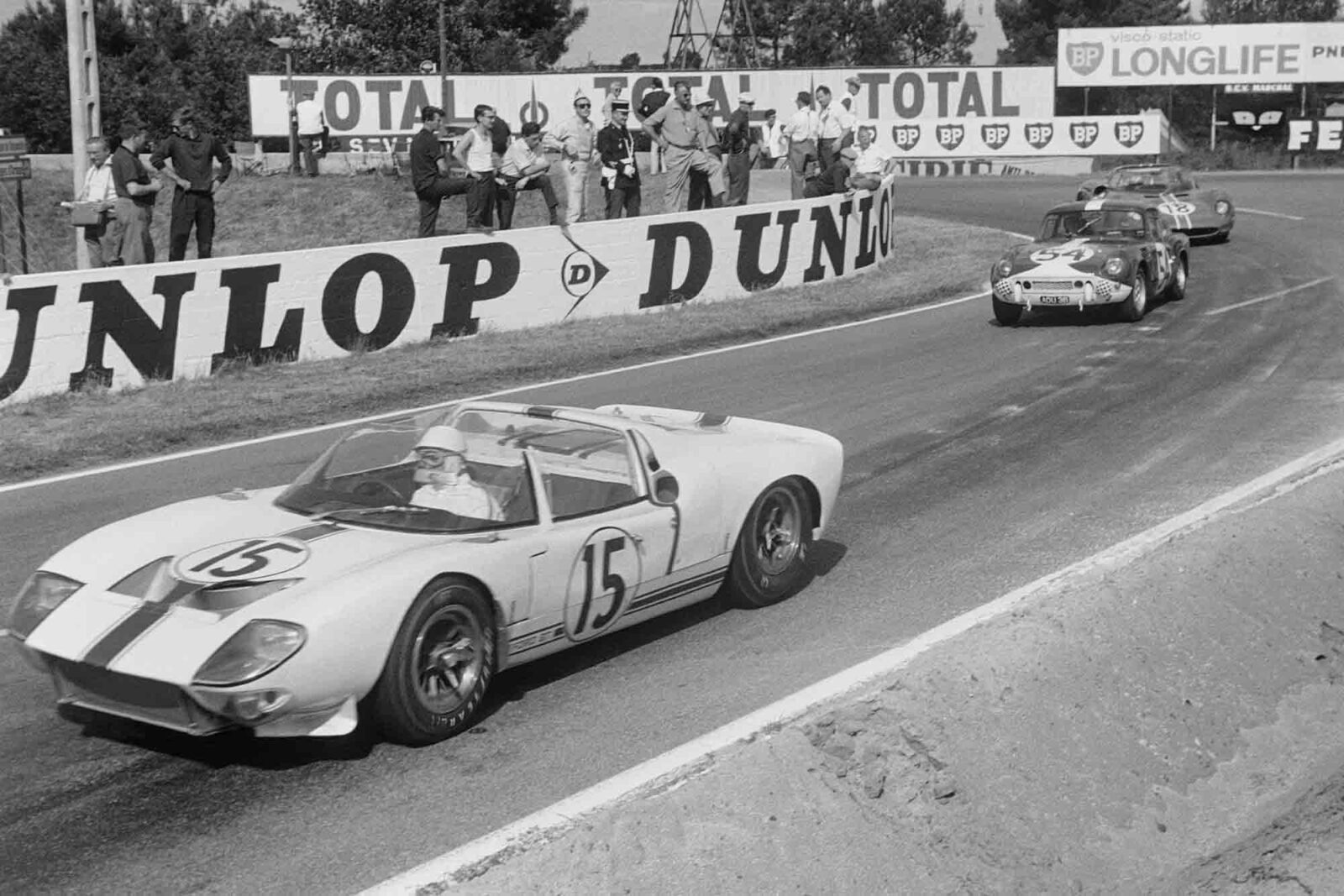

GT40 roadster at Le Mans in 1965

Motorsport Images

Like all well-worn accounts it’s probably only half accurate, but it makes for a good yarn nonetheless. Early in 1966, an agent acting on behalf of Enzo Ferrari approached Henry Ford II with a message. Il Commendatore had maybe, just maybe, been a little hasty in kicking him to the kerb three years earlier: if the old offer was still on the table, he would consider reopening negotiations. He wasn’t averse to a merger deal. But Mr Blue Oval had moved on: Ferrari had nothing that interested him any more. After all, he had the GT40 in his arsenal.

Backtrack to ’63 and Ferrari had been keen to sell the majority share in his eponymous marque to Ford. It was he who first made the approach, albeit by the rather Cold War thriller method of sending over an envoy to doorstep the German consul in Milan. Word eventually reached Detroit and Ford’s general manager Lee Iacocca, who had already laid the groundwork for the Total Performance programme: Ford would triumph in every conceivable category and then bask in the reflective glow – win on Sunday, sell on Monday and all that. By taking over Ferrari, or at least the majority shareholding, it could bypass the start-up process.

Except protracted negotiations between the defiantly self-directed Italian autocrat and bottom line-minded Detroit execs ended amid enmity. Notoriously ambivalent to anything stars and stripy, the sixty-something proclaimed: “My rights, my integrity, my very being as a car manufacturer, as an entrepreneur, as the leader of the Ferrari works team, simply cannot work under the enormous machine, the suffocating bureaucracy, of the Ford Motor Company.” With a serious crimp in his karma, Iacocca created a task force to conjure up a feasibility study: just how much would it cost to give Enzo a good drubbing at Le Mans?

“These guys turned up in their shiny suits and had absolutely no idea. They understood stock cars where all you had to do was turn left every 30 seconds, but not what was involved in winning a race like the Le Mans 24 Hours”

Quite a lot, as it happens, but the automotive giant’s coin attracted a cadre of able racing men. Among them was Lola founder Eric Broadley, whose delicious John Frayling-styled GT caused a furore at the 1963 Racing Car Show. Although the small-block Ford V8-powered design never covered itself in glory trackside, it nonetheless provided the kernel of the GT40. Broadley effectively took a year’s sabbatical to conceive a new car from the new Ford Advanced Vehicles Ltd facility in Slough, under the watchful eye of former Aston Martin team manager John Wyer. Heading the project was ex-pat Englishman (and former Jowett chief designer) Roy Lunn, who headed up Ford’s Advanced Vehicle Concepts division.

“Ford’s men certainly made an impression,” recalls Broadley’s then-lieutenant Tony Southgate. “In the early ’60s, Lola Cars operated out of a glorified lean-to in Bromley. Eric and I worked in a small chipboard office that was above the lathes. Anyway, these guys turned up in their shiny suits and had absolutely no idea about motor racing. Well, that’s not true: they understood stock cars where all you had to do was turn left every 30 seconds, but not what was involved in winning a race like the Le Mans 24 Hours.

“The one thing that really stuck in my mind was the manuals. Ford produced a manual for everything. If you wanted to know how to make a steering arm, for example, you consulted the manual for making steering arms. There was no deviating from the script. Well, motor racing is about as far removed from that as you can get. It’s all about being adaptable and designing things from scratch, often in a hurry. I’m amazed Eric stuck it out as long as he did, but then he did get a nice shiny factory out of the deal…”

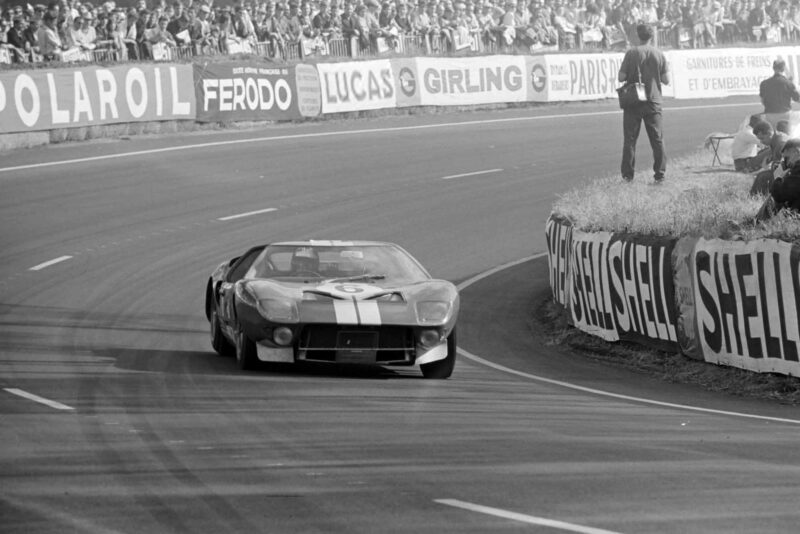

GT40 of Ronnie Bucknum/Herbert Müller at le Mans ’65

Motorsport Images

Initial testing with the GT40 in April 1964 uncovered a straightline stability issue, with both Jo Schlesser and Roy Salvadori crashing during the Le Mans trials. And the Colotti gearbox proved a mite delicate. The monocoque, however, was massively over-engineered (Broadley had wanted aluminium, but Ford insisted on steel), which very likely saved some lives as a result.

Not least that of Sir John Whitmore, who suffered a huge shunt at Monza early in ’65: “It was during winter testing; Richard Attwood and Roy Salvadori were the other drivers. Early one morning while the track was still greasy I went past the pits, and at the long curve at the end of the pit straight I lifted off from about 160mph and the car just seemed to accelerate. The brakes were relatively ineffectual and so I went straight on into the forest and just managed to miss poleaxing myself on the first guardrail. The young trees destroyed the car but also broke off, so it retarded at a reasonably safe rate. I got out with no damage other than slight seatbelt bruising.

“Wyer was a bit pissed off and said that Salvadori would have been able to save the car, which I just don’t believe. He didn’t seem to care much about the fact that I had just survived a crash that could easily have killed me. Later on he discovered that the throttle was still stuck open due to a stupid mistake by a mechanic. Wyer apologised profusely – not something he was accustomed to doing. He was a tyrant, but I still liked him.”

With all three entries having retired from the maiden Le Mans bid in ’64, Carroll Shelby was brought in to shake things up for the following year’s attack. Enter the GT40 MkII. Ford set up the Lunn-fronted Kar Kraft subsidiary in Detroit to design and build prototypes, while racing’s most famous Stetson wearer now ran the show from California. Powered by the elephantine 427cu in V8, the new strain also received a stiffer chassis, ZF ’box, bigger tanks and quick-change disc brakes. After the prototype lapped the five-mile oval at Romeo, Michigan at over 200mph, Ford’s top brass reasoned that Le Mans – with its long Mulsanne straight – would become a GT40 benefit. Two big-block cars would head the attack, with four smaller-displacement cars – now with 289cu in bent-eights in place of the earlier Fairlane ‘Indy’ units – providing covering fire. The result was six DNFs – not quite in keeping with the Total Performance mantra.

Consequently, it was argued that one team could run only three cars at a stretch, so, besides Shelby American, works entries were farmed out to famed stock car entrant Holman Moody and to British squad Alan Mann Racing for the following year. Wyer was sidelined with making the MkIII road car. All of which made for an uneasy alliance and inter-team rivalries with the theoretical flow of information between them being just that.

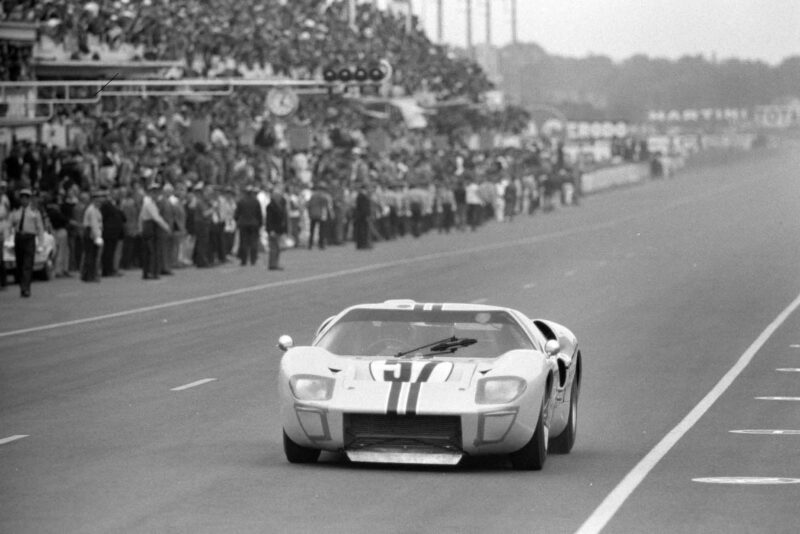

Paul Hawkins at Le Mans ’67

Motorsport Images

Nonetheless, the ’66 season got off to a flier with a 1-2-3 sweep at Daytona, followed by a 1-2 in the Sebring 12 Hours. Then came Le Mans. Having already won both prior events, Ken Miles and wingman Denny Hulme were leading by a country mile, and the 47-year-old looked like becoming the first man to win the big three sports car races in the same year. Then Ford’s publicity-conscious execs requested he slow down to make a dead heat 1-2-3 finish. Inexplicably, Miles backed off at the flag and handed the win to Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren. Two months later, the Sutton Coldfield-born ace perished after crashing the J-car prototype in testing. But it was this strange device, with its aluminium honeycomb chassis and breadvan tail, that would form the basis of the ultimate – and unbeatable – super-Ford: the MkIV, which took Le Mans honours with Dan Gurney and A J Foyt in ’67, having already triumphed at Sebring.

And then the FIA promptly capped engine capacity at five litres to stop it from coming back. Meanwhile, free of Ford’s constraints, Wyer instigated the construction of three new Mirages – essentially a GT40 hull with a smaller greenhouse conceived by Len Bailey. Regulations then changed so the JWA squad reverted to the usual outline and scooped the 1968 World Sports Car title with Lucien Bianchi and Pedro Rodríguez, chalking up another win at La Sarthe for the old stager.

By 1969, the GT40 was truly obsolete. Yet as Le Mans rolled round again, the Anglo-American challenger was still in with a shout, the end result being the closest (unstaged) finish in the event’s history as young buck Jacky Ickx battled with veteran (well, 41-year-old) Porsche driver Hans Hermann to the bitter end. This being the same year that Ickx famously ambled to his car in protest over the traditional sprint, a practise he deemed dangerous.

“Ford achieved its goal of nixing Ferrari at Le Mans with a racer that handily doubled as a dizzyingly beautiful road car”

Outmoded and outgunned: not quite how the GT40 came in but a suitable denouement for a car that came to define corporate involvement in motor racing. One that continued to win big despite outliving its natural lifespan. With umpteen privateers acting as back-up players, the number of results accrued by the GT40 in period ran into the hundreds. And it’s never really gone away, the model finding its way into historics while barely a decade old.

Respected GT40 pilot and restorer Dean Lanzante is in no doubt as to the model’s continued appeal to the historics fraternity: “It’s almost a modern car in terms of balance. We’ve only ever done MkIs – must be six or seven now – and you can tell that it’s an endurance car. Unlike, let’s say, a Ferrari 250LM, you can take one down to a bare tub in a matter of minutes. Nothing is ever a struggle except perhaps removing the flywheel, and even that’s not that big an issue. It’s the perfect car for long-distance events like Tour Britannia. I mean, you can fix it at the roadside and should anything major go wrong you don’t have to wait a year to get parts specially cast.” Ford achieved its goal of nixing Ferrari at Le Mans – Maranello’s finest hasn’t won at La Sarthe since ’65 – with a racer that handily doubled as a dizzyingly beautiful road car. One that’s still compellingly charismatic, hence the more recent arrival of the crass ‘retro’ GT supercar. More than anything, the GT40 is remembered fondly by all those who witnessed its rise to greatness from different sides of the pitwall, and regarded with awe by those of us who didn’t.

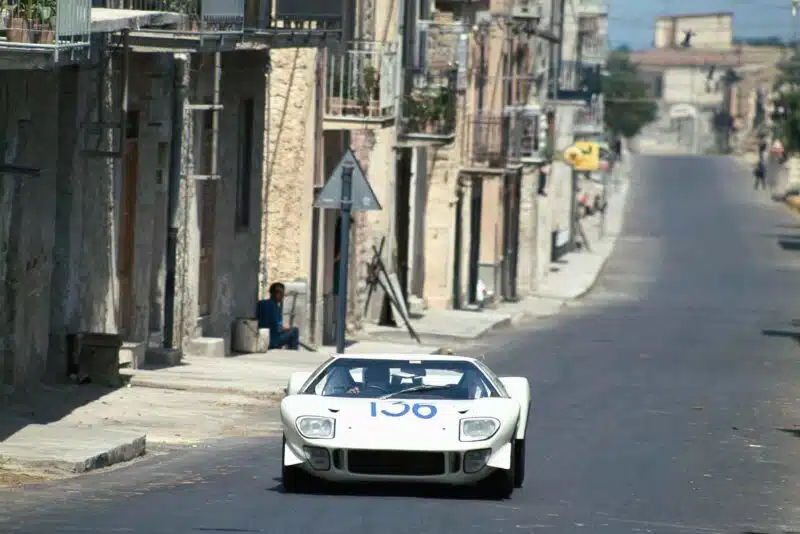

Terry Drury in his GT40 at 1968 Targa Florio

Motorsport Images

“I raced one”

Gordon Spice

This gregarious ace made the leap from Minis to prototypes after wangling his way into a GT40

“I got the opportunity through Movi Cooper, the Spanish concessionaire for Cooper Cars. I came to be testing the Escuderia Montjuich Group 5 Mini which had been entered in the Spanish Touring Car series. The owner was José María Juncadella de Salisachs, who was a Spanish aristocrat and playboy. ‘Hunky’ bought a GT40 off ‘Hawkeye’ [Paul Hawkins] and I sort of engineered a drive with him in the 1969 BOAC 6 Hours at Brands. You know, it wasn’t as big a leap as you might imagine. Driving Minis on the limit was very demanding, but that GT40 was effortless: you just sat there and drove it. Anyway, we retired at Brands but raced it all over the place and earned class wins in the Spanish series.

“I remember us doing a six-hour race at Jarama. ‘Hunky’ always liked to do the opening and closing stints. I would do the rest which was fine by me as it meant I got plenty of seat time. With about an hour to go, I came in to hand over the car. We had a two-minute lead in Group 4 and were third overall. Well, with half an hour to go, he came into the pits because he was thirsty: he wanted a Coke! He didn’t get one! Fortunately we won our class with 20 seconds in hand. Without doubt, the GT40 was the nicest racing car I ever drove, and that includes the Spice C2 cars.”