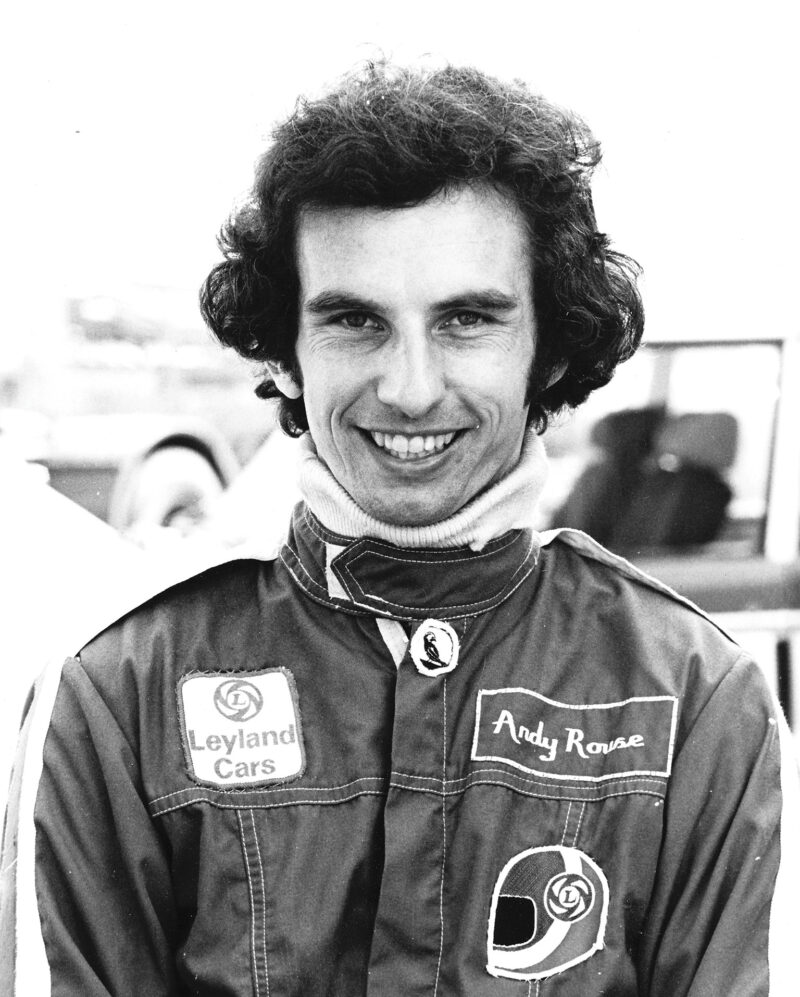

Lunch with Andy Rouse

Don’t be fooled by the quiet manner. This multiple saloon car champion is equal parts racer, engineer and forceful foe

James Mitchell

In most branches of professional motor sport, the man who is doing the driving is not the same as the man who is doing the engineering back at the workshop.

A good tester, sensitive to a car’s track behaviour and how he wants it to improve, will communicate what he discovers to the engineer, who will then modify or re-engineer the car to try to meet his driver’s wishes. But when the driver and the development engineer are one and the same, you can shortcut a whole stage in the process of building a competitive racing car.

This – along with the ability to be not only very fast, but also hard-nosed in one of racing’s hardest-nosed categories – was a key factor in the long success of Andy Rouse. While working as a tester and development engineer in the 1970s for the mercurial Ralph Broad at Broadspeed, and then running his own Andy Rouse Engineering, he also managed to take four British Touring Car Championship titles, three of them consecutively. In those multi-class days consistency in a small car could beat the big cars to overall points victory, but Andy also won his class in the series a further five times. In the races themselves, over 20 seasons he scored 60 outright and class victories, which at the time was a record. (These days it’s rather different: with three races per round, Jason Plato is on his way to his 100th win.)

Rouse graduated from grasstrack racing to compete – with some success – in Formula Ford Dulon

Motorsport Images

Andy is out of motor sport now, dividing his time between his commercial property business, exercising his 600-horsepower sports cruising boat, and riding his Suzuki trail bike in the Welsh hills. But the Rouse connection with racing remains, for his son Julian is the general manager of Christian Horner’s Arden Motorsport, running cars in GP2, GP3, Formula Renault 3.5 and MSA Formula.

Now 67, Andy still has the same rangy build as he had when we were both racing Escort Mexicos 43 years ago, and for our lunch at the Bluebell restaurant at Sunningdale he chooses a healthy meal: yellow fin tuna, wild sea bass and gooseberry fool.

He’s a country boy, born in Gloucestershire into a family that could hardly have been less car-orientated: his father was a market gardener. Nevertheless the fields and country lanes meant there was plenty of room to crash around in the old Ford Popular he got hold of when he was 13. Then came the local sport of jalopy racing. The Gloucester & District Jalopy Club ran races around a quarter-mile grass oval, and before he left school Andy built his own jalopy, a weird mixture of Singer Le Mans chassis and side-valve Ford 1172 engine. “It taught me some good early lessons. You’d have eight cars racing side by side, no grip on grass of course, and you didn’t really use your brakes, so I learned how to deal with whatever the car decided to do. A friend from school, Ian Biscoe, used to come along and help me. It must have taught him something, too: he ended up running Cosworth in America.

“I spent four years doing a general engineering apprenticeship in Gloucester with Muir Hill, who make those big yellow diggers and road-building tractors. There was nothing automotive about it, but it taught me how to make things, and how to weld. By the time I was 20 I’d managed to scrape together the funds to buy an old Formula Ford Dulon. FF was new then, still pretty cheap, using road tyres. Ian came along as my mechanic: neither of us knew anything about racing, but he was really handy, and he could build up an engine.

Forging his reputation in an Escort Mexico in 1979 when racing was still a novelty

Motorsport Images

I just raced on the local circuits, Castle Combe, Thruxton, Llandow, but eventually I won the BRSCC South-West FF Championship.

“Dulon noticed that, so they gave me a deal on a newer chassis. I wanted to progress to the national championship, which meant I needed a good engine. I read that Broadspeed, who’d built up a top reputation in touring car racing, were going to be building FF engines, so I called up Ralph Broad. He told me to come and see him. I went up to Southam and Ian came with me, and we ended up with an FF engine – and a job each. That’s how I moved from being a digger mechanic to being a racing mechanic.

“I started off as a cylinder head grinder. Broadspeed was making engine kits for Ford road cars in those days. You could buy a package from your Ford dealer: polished head, reprofiled camshaft, rejetted carburettor. I was grinding heads all day, 60 hours a week, which meant I didn’t have any time to prepare my own Formula Ford. And in the national championship I was up against people like Emerson Fittipaldi and Tony Brise. It was all good experience, but on my mechanic’s wages it wasn’t going too well.

“Meanwhile Ford had announced a one-car British championship for the Escort Mexico, which was a pushrod 1600 version of the Escort. Ralph sold me a car – at cost, but I still had to pay for it – and I prepared it in the workshops in my spare time. I painted it in the Broadspeed colours of metallic maroon [actually Rolls-Royce regal red] with silver roof. Ralph pointed me towards a few extra tweaks, and after the first couple of rounds I really got the hang of it. I found I liked racing saloons more than single-seaters, and I just clicked.”

I can confirm that: I beat him into fourth place, just, at the first round, but then he got in the groove and for the rest of the season none of us saw him for dust.

Ralph Broad realised that this lad Andy was growing into a very talented racer, and needed more opportunity. For 1973 Bristol Ford dealer Vince Woodman was racing a 1300 BDA-powered Broadspeed Escort in the British Saloon Car Championship (as the BTCC was then called). Ralph persuaded Vince to buy a full-house 2-litre Escort as well, a car he’d built the previous season for David Matthews, and enter it for Andy.

first BSCC title came in 1975 with Broadpseed Dolomite Sprint

Motorsport Images

This moved Andy abruptly into the big time. He rose to the occasion in the very first round at Brands by coming third overall behind Frank Gardner and Dave Brodie, and then took second place in round two at Silverstone behind Brian Muir’s big BMW and ahead of Gardner’s Camaro. At the end of the season he’d finished second overall to Gardner in the championship, and had won the 2-litre class with ease.

“Coming after the Mexico, with its near standard engine and road tyres, the Group 2 Escort was a real step up. It was a proper racing car: 2-litre Cosworth BDA engine, big slicks 10 inches wide at the front and a foot wide at the back. Broadspeed was building Group 2 cars for various customers, and effectively running Ford’s works team in the championship. I was workshop foreman now, but Ralph was also using me as the test driver, so I was doing a lot of circuit mileage.

“Working for Ralph there was never a dull moment. He was a real character: always like a coiled spring, living on his nerves, chain smoking, talking very fast, every third word unprintable. We got on well, and he was very good to me. He was my mentor, taught me how to analyse things mechanically in racing. I developed the cars, I got the results, and gradually I became his right-hand man.

“For 1974 the saloon racing rules all changed. There was a recession on and there wasn’t much money about, so the British championship switched to Group 1, with cars having to stay close to standard. Somehow Ralph did a deal with British Leyland to run a works team of Triumph Dolomite Sprints and, with very few modifications allowed, we had to make them raceable. My jalopy racing stood me in good stead, because the Dollys just wanted to oversteer, and they had no brakes. The rules said we had to use the standard brakes, calipers and pad sizes, which were the same on the Sprint as on the basic Dolomite 1300, and the usual DS11 pads used to melt. So we found some aircraft brake pad material, which is sintered, and cut that to fit.” After a lot of painstaking development work, the Dolomite was a winner. In 1974 Andy headed his class in the championship again, and in 1975, with 12 wins out of 15 rounds, he finally got the title of overall British saloon champion.

“I won that by a bonnet-length. Bernard Unett had been winning his class everywhere in the little Hillman Avenger, and going into the last round at Brands Hatch I had to be sure to win my class to beat him to the title. Brian Muir was racing Bill Shaw’s Dolomite that year, and he was the one guy who could give me a problem. Before the race Ralph did some sort of deal with Bill Shaw, I don’t know what, but Bill said he’d tell Brian not to beat me.

Jaguar’s 1977 ETC programme was rich with promise, but not with results

Motorsport Images

“Well, Brian was a pretty tough racer. He got ahead of me at the start, and I didn’t want to attack him too hard and have us both off. So we raced nose to tail for the whole 20 laps, and coming into Clearways, the last corner on the last lap, he was ready to let me go by – and there was a yellow flag: no overtaking! So I was still behind as we went for the finish line, and in the last few feet Brian eased off the throttle a tiny fraction, I got alongside, and we crossed the finish line with me ahead by a bonnet. So he honoured the deal, but he made me work for it.”

Encouraged by this success, British Leyland decided to raise its sights, and take on the European championship with, of all things, the big 12-cylinder XJ saloon. So for 1976 Broadspeed got the job of building a racing version of the two-door XJ12C: and Andy got the job of developing it, and then racing it. Jaguar now paid his salary.

“We were presented with this soft luxury barge and had to turn it into an effective racing car. It wasn’t an easy task. There were a lot of big company politics involved, between British Leyland and Jaguar, and between Jaguar and us. In fact Jaguar, with its history of Le Mans wins and the great days of the 1950s, wanted to do it alone. It didn’t actually have a competitions department any more, but there were still people there who thought they should be developing it. So we didn’t get much help from Jaguar.

“For a start, that big V12 motor was quite a challenge. Power wasn’t the problem: it was only a two-valver, single cam each side, but we got a good 560bhp out of it. But the rules said you had to keep the wet sump, and it was a long engine with a very shallow sump. The engines kept blowing up because of oil surge, and we had to design more and more exotic sumps to keep it all together. Six months before the programme finished the rules changed and we were able to build a dry-sump car, but by then it was all too late.

“British Leyland was in such a hurry to wave the flag that it started to publicise it before we’d even got the first car running, so expectations were way ahead of what we could do. It was September before we finally got one car to a race, the TT at Silverstone, and Derek Bell put it on pole. But we had a problem with rear hubs breaking. We had 19-inch diameter wheels, 14 inches wide at the back, and Jaguar insisted we ran with standard rear hubs. They promised to make some better ones, but it never happened.

Performance in Britain’s Porsche 924series earned Rouse international opportunities

Motorsport Images

“For 1977 we ran two cars in the European championship, Derek and me in one and Tim Schenken and John Fitzpatrick in the other. The Jaguars were very heavy – 1400 kilos – and nowhere near as fuel-efficient as the lightweight BMW 3.0 CSLs. They could do a three-hour race with one stop, whereas we had to make two stops. We were faster than they were, but we couldn’t make up enough to cover the extra stop.”

That season was an expensive disaster. Two cars started in seven rounds of the championship, and frequently they qualified fastest: but out of those 14 starts they posted 11 retirements. However, there were a couple of high spots. The first came in the Nürburgring Four Hours. The XJ12 scored its first proper finish when Derek and Andy came home a magnificent second behind the fastest BMW, the Gunnar Nilsson/Dieter Quester CSL.

“Hustling the XJ12 around the Nordschleife in a four-hour race was like being sentenced to hard labour. Even the front wheels were 12 inches wide, and there was no power steering – we’d deleted that to save a bit of weight. And the clutch, to cope with the power, was so heavy you could scarcely push it down.”

Then in the TT at Silverstone, the track where he had done so much endless testing in the car, Andy set pole by more than half a second. In the closing stages he emerged from his inevitable extra pitstop in second place, and started to wind in Tom Walkinshaw’s leading 3.0 CSL – until, with eight laps to go, he found a sheet of oil across the track at Abbey from a car that had blown its engine moments before. At once the Jaguar was in the bank; but it was so far ahead of the rest that it still earned fourth place.

“Leyland pulled out after that. We didn’t even go to the last two rounds. After all our work, it was really frustrating that they didn’t stay in for one more season, because the BMW 3.0 CSL was out of homologation, and I reckon we could have got the XJ12 right and won the championship.

“And then Ralph decided to stop. His ticker was pretty rough, I think, but also his daughter was tragically killed in a road accident, and that hit him very hard. So he retired to Portugal, and Broadspeed was sold to John Handley, who’d raced for Ralph in his Mini days.

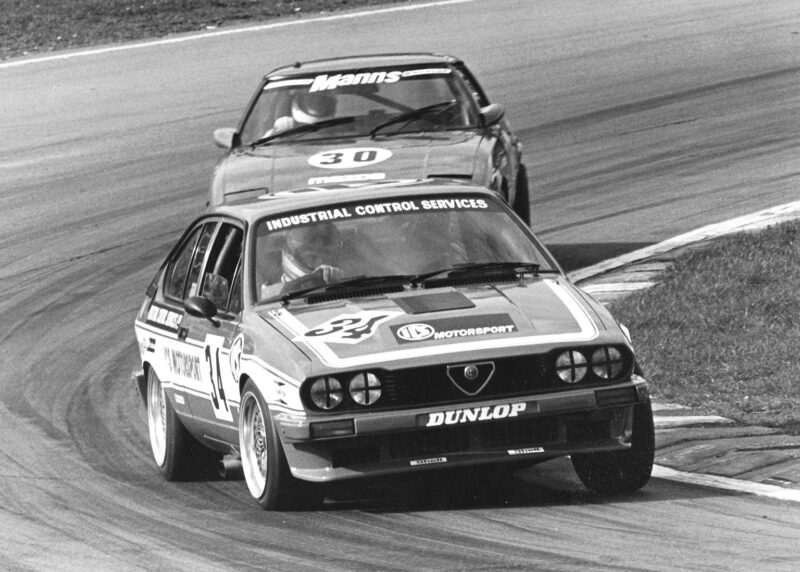

After a controversial season, Rouse (ICS Alfa) was eventually awarded the 1983 BSC title

Motorsport Images

“With Jaguar out and Broadspeed sold, I was left trying to turn myself into a self-employed racing driver and tester. What saved me was a friend who had a company that made industrial furnaces, and he gave me a part-time job as a welder/fabricator. So I’d gone from British saloon car champion and works Jaguar driver to welding up boilers.

“But I had some drives for Tom Walkinshaw in BMWs, and Alan Minshaw lent me his Opel Commodore for production saloon races, all of which kept my face in. That led to a drive with Gordon Spice in his 3-litre Capris, and I was on the winning team in the 1981 Willhire 24-hour race at Snetterton in an Opel Commodore.

“Things didn’t go well for John Handley at Broadspeed, and in 1981 he had to close it down. I decided that was the right moment to set up my own operation, and I founded Andy Rouse Engineering. Vic Drake, who’d managed the road car side at Broadspeed, came in as my partner. We bought a lot of their old equipment, and to start with it was just Vic and me and a couple of guys. My lucky break was meeting Pete Hall.”

Hall’s company, Industrial Control Services, had made him a wealthy man, and he was an enthusiastic saloon car racer under the ICS banner in an Opel Commodore. “He wanted the best of everything, so we began to build his engines, and I’d test his car and sort it for him. ICS ended up sponsoring me for 11 years.

“For 1983 I was going to race a V8 Rover for Martin Thomas, but just as the season was starting he withdrew, which left me high and dry. Meanwhile Pete had bought an ex-European championship Alfa Romeo GTV, and he’d done a couple of races with it and didn’t get on with it at all. We did a test on the Brands Hatch long circuit and he said, ‘I can’t drive this thing, you’d better drive it.’

“I’d missed the first three rounds, but with the Alfa I won my class in six of the remaining eight rounds, which made me class winner and third overall behind the two Tom Walkinshaw Rovers of Steve Soper and Pete Lovett. And then the Rovers were disqualified.” It was discovered that Walkinshaw had changed the tappets from hydraulic to mechanical, which the rules didn’t allow. He insisted it was for maintenance reasons, and there was no performance advantage, but after months of argument the disqualification held, and Andy was champion.

Rouse ran works Toyota Carinas in the BTCC for two seasons. This is Snetterton in 1992

Motorsport Images

“For 1984 Pete Hall did a deal with John Davenport, the Austin-Rover competitions boss, to run a Rover alongside the Walkinshaw cars, which were effectively the works team.

We beat them twice in the first five races. Meanwhile the row about the 1983 disqualification had got as far as the High Court. In June Davenport made a big dramatic statement announcing that, in protest, the Austin-Rover works cars were being withdrawn from the 1984 series. That pretty much left things to us. I won five of the remaining six rounds, and I was champion again.”

At this time Ford was keen to develop the Sierra ahead of the launch of the planned Sierra Cosworth, and they came to Andy to develop and run a works car for 1985. “This was the Sierra XR4Ti, which used a version of the American Pinto engine, 2.3-litres, four cylinders, single cam, but turbocharged. It was quite basic, just two valves per cylinder, but if you turned the boost up you had more power than the Rovers, and more torque.”

Andy won nine of the 12 rounds outright, to take his fourth British title, and his third on the trot. The following year he won his class again. “Ford loved it, because all the rounds were on BBC TV with Murray Walker and Steve Rider, getting big audiences. Ford backed it up with a TV ad campaign too, featuring our team.”

For 1987 the series had changed its name from BSCC to BTCC, and the XR4Ti had given way to the Sierra Cosworth, with the 2-litre twin-cam YB-series engine. “Then halfway through that season came the RS500 version, with a much larger turbo and bigger injectors, different rear suspension geometry and a bigger rear spoiler. It was quite challenging to drive, because we were making 520bhp and over 400lb ft of torque. To homologate it, 500 examples had to be sold, which made a fun road car. A good RS500 is very collectable now.

Winning smile: Rouse in 1975

Motorsport Images

“Ford paid us to run the Sierra development programme originally, but then the RS500 took off, and in 1988 there were up to 16 of them on the championship grids. So they didn’t need a works team any more, and instead they ran a bonus scheme, with £5000 if you won a race.

I won nine of them, so that was quite good. That brought me another series class win, and I managed it again in 1989. Also in 1988 I did the TT, which was then a round of the European Touring Car Championship. Alain Ferté and I won that, beating all the BMWs and Eggenberger Sierras.

“I was running the company, developing the cars, and racing them, which meant long days and seven-day weeks. But it was very satisfying because it was my own operation. We were employing about 30 people by this time. We built more than 100 racing engines for RS500s, and we were also making road cars, including our version of the Sapphire Cosworth, the 304-R. We made nearly 90 of those, and I still get people asking about them today.

“For 1991 the RS500 was about to run out of homologation, and we were going to lose a lot of the cars off the grids. BBC Grandstand was giving us great coverage, and we needed to be sure that the standard of racing remained high. So with several of the other team principals we instigated TOCA – short for TOuring CArs – to administer the series, and it was run out of my office in Coventry. We came up with new rules for a 2-litre one-class championship, which we called Supertouring. Alan Gow came in to run it, sort out the licence from the MSA to run the series, organise the TV deals, the test days, everything. He was the perfect man for the job.

“With no more RS500s we switched to Toyota and ran its works Carinas. I finished third in the series, and in 1992 I scored my last two BTCC wins, taking my total to 60. Then at the end of 1992 Ford came back to us and said, We’ve got this new thing called a Mondeo, and what are you going to do about it?

“In Supertouring you were allowed to use any engine from the same manufacturer’s range. The Ford Probe in America used a 2.3-litre V6 actually made by Mazda, so we destroked that down to 2-litres. We discovered from the start that the Mondeo was much too heavy. So Ford opened up the production line on a Sunday and sent 30 special shells down the line. They reduced the metal thickness on all the panels, and took out anything that we didn’t need – all the crash strengthening in the doors, lots of brackets and stuff.

Rouse was best in class in the Sierra XR4Ti in 1986, but finished only third in the overall standings

Motorsport Images

“We did the first engines, just to get the testing under way, while Ford got Cosworth to do the full engine development programme. They finally got the finished engines to us in June, and suddenly we had a competitive car. Paul Radisich had come over from New Zealand to drive for us, and although we only did the second half of the season he did a really good job, finishing third in the series with three wins. He was third again in 1994, which was my last season as a driver. I wasn’t too keen on hanging up my helmet, but I’d done 22 seasons as a professional racer, and the business was still there to be run. And I think Ford wanted a younger driver, so we got in Kelvin Burt as my replacement.

“It was at the end of the 1993 season that we ran Nigel Mansell in the TOCA Shoot-Out at Donington. He was reigning Indycar champion and the previous year’s F1 world champion, but he didn’t really know what he was getting himself into: I think he thought it was just going to be a celebrity race. We tested for a couple of days and to begin with he couldn’t get the hang of the Mondeo – he thought the braking distances should be the same as a Formula 1 car’s – and he went off two or three times. We’d brought two cars, and we put him in the second one while we repaired the first one, and went on like that. But gradually he got the hang of it, he was improving all the time. And he was brilliant to deal with.

“It must have been the best publicity Ford ever got out of going motor racing. The hoo-ha started on the Thursday before the race, stories in every paper, and on the day 70,000 people paid to come and watch. He turned up with all his minders, and a TV crew constantly sticking a camera up his nose, and all these people hanging around him. It was bizarre. He spent hours signing autographs – and of course in the race he crashed the car. Really wrote it off. That was headlines across the world: Nigel Mansell in Mondeo crash! After that car clubs and charities came on asking us to give them damaged panels from the car that they could auction. When we had given away all the panels, we painted a big red 5 on any other bent panels we could find and sent them those.

“For 1996 Ford took their deal away from us and gave it to Dick Bennetts and West Surrey Racing. They’d had a change at the top at Ford. The new motor sport manager was a New Zealander, and Dick Bennetts is a New Zealander. I don’t know if that had anything to do with it. Anyway, it made no sense to me, and I was a bit knocked by that after all the work we’d done for Ford. We’d been on the podium 36 times with the Mondeo. West Surrey didn’t build the cars themselves, they went to Reynard to get that done, and I think in all the time they ran those cars they only won one race, so it was a bit of a disaster for Ford.

“We wanted to carry on, but the only deal we could find was to run out-of-date Nissans. Then we tried to get Toyota back in, but that didn’t work out. By that time we’d run out of options, so I took the difficult decision to close Andy Rouse Engineering. We sold off the equipment and got rid of the factory, but the business itself wasn’t a sellable item because it was all centred around me.

“Later on, Pete Hall and I tried to get together an alternative to the BTCC called SCV8. The aim was to provide lots of speed and power and spectator excitement at low cost. The cars would use a common spaceframe chassis, with different road car bodies.

“Our first prototype had a Lotus V8 engine that Janspeed developed for us, under a Peugeot shell, and then we built a Jaguar X-type version. Because the engine, chassis and suspension were all the same, it would have been inexpensive. We took it to Nicola Foulston when she was running the Brands Hatch group of circuits, but before it got any further she sold out to Octagon, and that was the end of it.

“During my touring car career I raced some other stuff, too. In 1974, still fancying myself as a single-seater driver, I bought a March-BDA and raced in Formula Atlantic. I fitted that in with the Dolomite programme, until Ralph called me in and told me, in his usual muck-and-bullets way, that I had to decide whether I wanted to be a single-seater driver or a touring car driver, because he wasn’t going to have me trying to be both. That was the end of Formula Atlantic for me.

“And I did Le Mans three times, twice in a factory-entered Porsche. A dealer fielded a car for me to drive in the UK Porsche 924 Championship, and I finished runner-up in that series to Tony Dron. As a result the factory put Tony and me in one of three 924GTs it had entered for the 1980 24 Hours. It wasn’t very quick, but it was fuel-efficient, and by 10am on Sunday we had it up to eighth place overall. Then the engine went sick, but we still finished 12th. The next year I was paired with Manfred Schurti, and exactly the same thing happened. A valve burned out, so they took the plug out and we kept going, trudging round on three cylinders. It was pretty boring, but we finished 12th again. In 1982 I did it in Richard Lloyd’s 924. We didn’t get far: blew an engine in practice, started the race from the pitlane, and blew it again.

“I loved Le Mans, the race itself was brilliant. But back in those days – no doubt it’s very different now – if you were a Porsche factory driver you weren’t made to feel very special, at our 924 level anyway. It was the car that mattered, the driver was just an accessory to get it around the track. There was nothing laid on, just an empty caravan behind the pits: sort it out yourselves, boys.

“Outside the BTCC I raced touring cars at Macau a couple of times – what a wonderful track – and Bathurst, which was pretty challenging in an RS500. We were doing 185mph down Conrod Straight, every lap. Of all the cars I raced, I look back on the RS500 with the most affection – that, and the first Group 2 Escort in 1973.

“In 2003, just for a bit of fun, I did the Britcar Series with an 11-year-old DTM Mercedes 190, and my co-driver was my son Julian. I prepared the car in my garage at home, and we won the championship. And I’ve done the Goodwood Revival: in an E-type in the TT, in one of those hump-backed Volvos, and I even drove a replica of my Dolomite Sprint up the hill in the Festival. It still oversteered!”

Meanwhile, Andy still can’t quite leave cars alone. His current fun project is a surprising one: a 1967 Cadillac Calais Coupé. “It’s the one with the stacked headlights. It’s got the big 7-litre engine, and I’ve put Edelbrock fuel injection on it, we’ve come up with a special cam, exhaust headers, 20-inch wheels, lots of tweaks. I like working on cars, and the American stuff is great, and simple to work on. And a lot of it is quite rare over here. If you turn up at a historic meeting at Silverstone in a restored Jaguar, no one bats an eyelid. We rumble into the paddock, six up, and everybody loves it.”

So Andy Rouse started out working on a jalopy: and half a century later he’s working on a Cadillac. Opposite ends of the motoring spectrum, maybe, but with both of them, just like all those victorious touring cars in between, Andy has always got as much satisfaction out of developing them as driving them. There’s a pleasing symmetry about that.

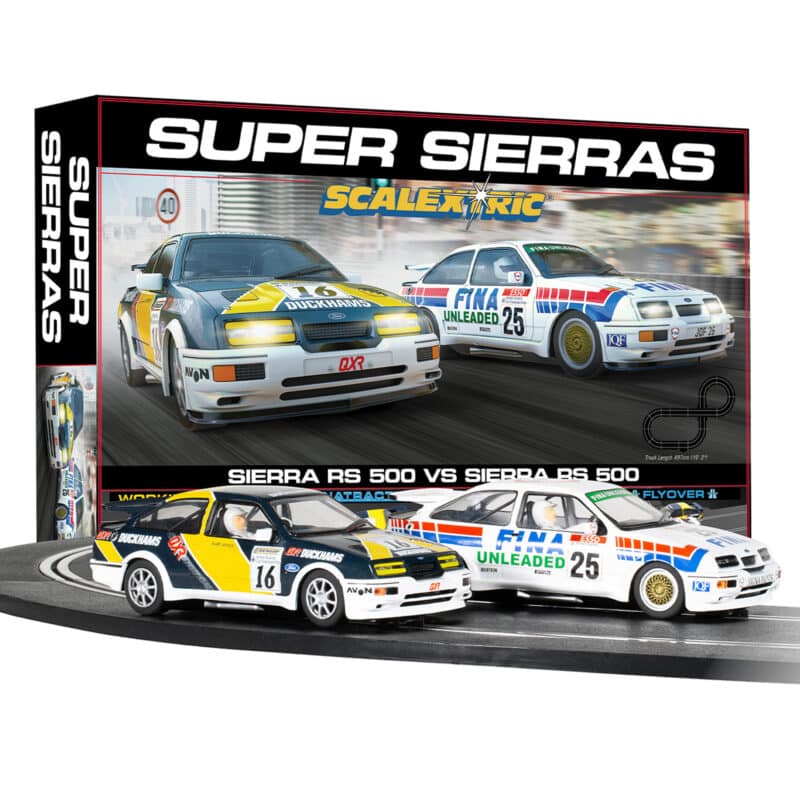

Scalextric Super Sierras Race set

£129.99

Take a nostalgic journey back to the thrilling Group A era of the 1980s with the Scalextric Super Sierra Set. Battle with two Ford Sierra RS500s — complete in old-school livery with working headlights — on a track with multiple layout options and a fly-over bridge.