Racing Lives: Cesare & Alex Fiorio

Cesare Fiorio began his motor sport career as a rally driver, then moved to head Lancia's WRC programme before becoming Ferrari's F1 team manager. His son Alex followed in his footsteps as a top level rally driver

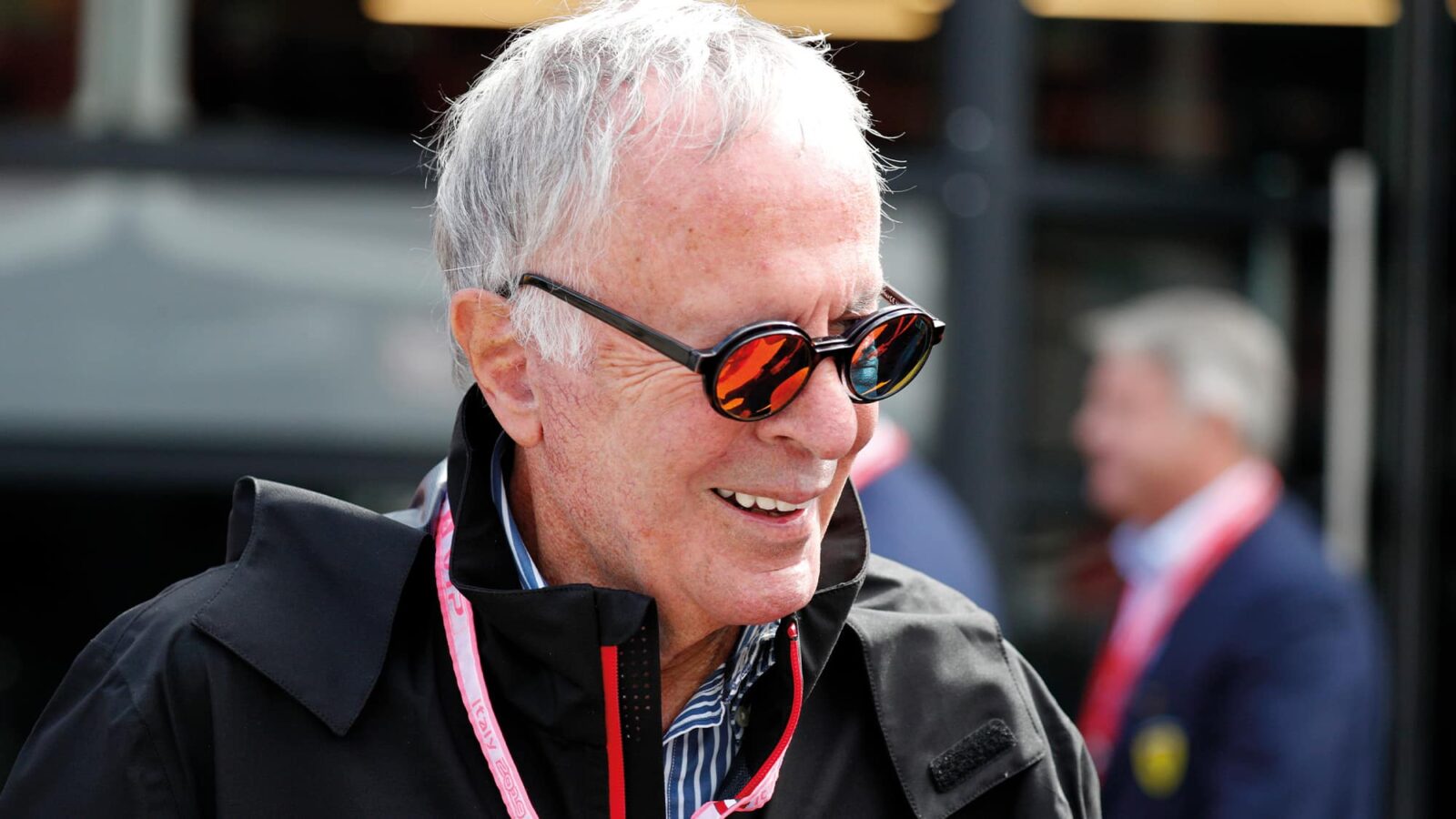

Cesare enjoyed a distinguished career as a team boss

Straddling both the worlds of Formula 1 and rallying, the Fiorio family has had a sizeable impact upon both. Cesare found his feet in rallying as a driver first, and then most notably as head of Lancia’s World Rally Championship during the 1970s, where he was closely involved with the legendary Stratos. He then moved to F1 and attempted to unite Prost and Senna at Ferrari, before going on to join Ligier and finally Minardi. He’s also raced powerboats and was even on the board of Juventus football club. His son, Alessandro (Alex), stuck firmly to the stages, making his WRC debut in 1986 before going on to rack up 51 starts and 10 podium finishes at the top level.

Cesare Fiorio

My father was running the family leather business and raced as a hobby. But during this time we had the world war and toward the end of that our factory became the central meeting point of the partigiani resistance movement. By the end of the war, which we had managed to finish how we wanted it to finish, the family business was no longer a good business, so he found a job with Lancia, running the press and public relations.

He had a lot of responsibility. The image of Lancia passed through his job, so it was a big effort and he was a busy man. But he kept work and home life separate. As a boy I wasn’t aware of Lancia.

Both Alex and I started in competitions without involving the family. In fact, except for my father, my family was against my idea of racing. I began my competition in 1959 or ’60, with the Cinquecento, and I managed to win two times the 12 Hours of Monza, and there were 80 Cinquecentos in this race! I started rallying when I bought a Fulvia Zagato from a private competitor in Genoa. I did this for three or four years, while at the same time working for a Lancia garage where I handled all the after-sales. But then I understood that if I wanted to get on I needed to have a lot of money, which I didn’t. So I thought I could organise it for somebody else, people who would trust me to run their car, and that led to founding the Lancia team, HF Squadra Corse, in 1963.

Alex Fiorio followed his father to the WRC

At the time, Lancia didn’t have a good competition car, and rallying wasn’t very popular in Italy, so I started in France, taking on René Trautmann – the ’63 French champion – and he drove a Lancia Flavia, and with him we won the French championship immediately, and the following year too.

Then we took on Finnish driver Pauli Toivonen and found Sandro Munari, and the three were doing well and, little by little, as we brought good result and good publicity, the factory found a small budget for us. After a couple of years, Lancia took us in, gave me a small place with two ramps and two mechanics, and that’s where it all started.

The HF name, for High Fidelity, already existed within Lancia, for the best customers who bought six or more. I added the Squadra Corse to the HF name, and Gianni Lancia already used the elephant symbol on his racing cars, including Ascari’s [D50] F1 car.

I remember during this time one of the biggest decisions I had to make. At the 1969 European Championship, Harry Källström was competing on the RAC Rally and his engine had a serious problem. We had one hour to repair it, which would need a very big effort, but we didn’t have a spare part to fix it, so I had to decide whether to take the part out of Timo Mäkinen’s engine. I made the decision to do it, and Källström won the rally and the championship. Lancia was now a serious contender.

When Fiat purchased Lancia, I was very nervous. We were beating Fiat all the time! I was called by Fiat’s director of personnel, and sure enough, he fired me. He wouldn’t listen to my arguments and thought that they could run things better. I was in a bad mood. But then a week later, he called me back and said, ‘We want you to run everything through Abarth, for Fiat and Lancia.’

This is when I made the decision to create a bespoke rally car and build the Stratos. For me it was really a big effort – my best effort, I feel – because there was a party in Fiat Group who didn’t really want us to complete this car, but we managed to do it.

This was a great time for Lancia, and then came motor racing as well. In 1989 I was at the Portuguese Rally and my press officer came running over saying, ‘There is an important phone call for you.’ It was the CEO of the Fiat Group, and he summoned me back the next day to Milan, even though we were leading the rally. ‘We need you to lead Ferrari,’ he said. This was fantastic – I had always wanted to go there. ‘When do I start?’ I asked him. ‘Tomorrow!’

When I arrived, I was pleased because I overheard two old mechanics talking. One asked the other, ‘What do you think of this new man we have?’ And the other man answered, ‘It is said he only eats bread and motor sport,’ so I felt I was accepted!

Cesare with Mansell and Prost during his second year as team manager in 1990

I brought in Alain Prost but I also wanted Ayrton Senna. So I set about making secret negotiations. I went to his house in São Paulo and later his house in Monaco, and we made a contract. It surprised me that it was done just between me and Ayrton – no managers, no agents, just him and me. He was very interested in coming to Ferrari.

Prost was not happy about this. So he used good connections he had in the top management of Fiat to stop Senna joining. I said, ‘I have signed this already with Senna. If he doesn’t join the team, I have to leave.’

This is one of only two regrets I have from my career; not having Senna join Ferrari. It was very bad. It changed life for three people.

It changed the life of Senna, because he didn’t come to Ferrari and died with Williams. It changed the course for Ferrari, because it didn’t win the championship, because Senna was competing against us. And it changed my life, because I quit the team.

When Lancia closed its motor-sport team, it was sad. But the people running it wanted too much budget and weren’t delivering. I lived and breathed it, but those after me were good technicians but not politically involved in Fiat Group, something I was good at.

Alex didn’t start to compete with cars. He started with skis because we come from Cervinia on the Italian side of the Matterhorn. He pushed a lot in sport, to a high level, and he won the Italian downhill junior championship, but then he hurt himself and that’s why he switched to cars.

The first thing he did was the Italian ice-racing championship. Then he switched to the Italian Fiat Uno Rally Championship. When he did, I said, ‘I’m okay if you want to do this, but if you arrive in place 38 or 42 or something like that then you abandon immediately!’ But he won seven races out of eight and became the Italian champion. It was a good place to practice for him because it followed the national rallies of Italy. With my background, though, it was a big problem for me and also for him, because he was my son. If he hadn’t had my name, he would have had better chances. I couldn’t put him in the works Lancia team, it wouldn’t have looked good. So he joined the Jolly Club team, which had links with Lancia, Alfa Romeo and Fiat.

By 1987 he was the [inaugural] WRC Group N champion, and I was proud of him but again, if he was not my son he could have been put in the official Group A team the following year but it was just not possible. It was not a good move in my time, but today you see it a lot.

Today I have my farm, an agri-business, and we welcome tourists here, in Ceglie Messapica, Apulia. Some people come for the Fiorio story. But many other people only find this when they arrive, such as in the Ferrari room. Then they realise, ‘Ah, it’s you! I didn’t realise it’s your hotel.’ But generally it has been much more relaxing than running a motor – racing team! My other regret is not putting Alex in an official car. He was competitive, he was very fast. He deserved it absolutely.”

Alex Fiorio

“Dad would drive me all over the place for the ski races, and there would be a lot of snow on the road, so he would be driving sideways everywhere, in a Fiat 131 that was a special project car. Sometimes we’d get stuck in a snowdrift and would have to push the car back onto the road! I had never been to a race or rally up to that point. It wasn’t until the Giro d’Italia Automobilistico passed by close to our house that I went to see a rally. It was nice to see it but I was still into skiing and had no real interest in it, personally.

Dad was travelling a lot and busy with work, of course, but when I was racing at the weekend he would always be there. He was always present for us – I have three brothers – and there were times when drivers would come to our house. I remember Andretti, Bettega, Biasion, Alén and Röhrl, and later when dad worked in F1, I remember Berger, Alesi, Mansell, Prost, and even Villeneuve visited when the Giro d’Italia was on.

My first experience of rallying was an ice race. My father knew nothing about it. I went to do it in my own car, an Abarth A112, as it was possible to do it without a rollcage, and I won. But I had no idea what I was doing. I asked the guy from Canonica, who was supplying tyres to all the competitors, whether he’d give me four tyres. He said he’d do it if I put many stickers all over my car. Auto Sprint, the weekly Italian magazine, wrote up a story about how the son of Cesare Fiorio had won a race. When my father saw it, he called me to his office, handed me the magazine, and I was a little scared but that’s when he made me the offer about the Fiat Uno Championship.

Alex carved himself a successful World Rally Championship career, here in full flow in his Lancia Delta Integrale on the 1988 Sanremo Rally. He’d finish second to team-mate Miki Biasion

When I started in the Uno, I didn’t think about my father’s reputation or worry about the pressure of performing and expectations. Of course, having a father like him helped me get a car and get into the sport in the first place, but once you are in that car it doesn’t help you at all. You are in the car, alone; if you don’t press the throttle you don’t make the time. I was one of the youngest drivers at the time to win the world championship. [Aged 22, Fiorio won the Group N production class of the 1987 WRC, driving a Lancia Delta Integrale in the newly introduced FIA Cup for Drivers of Production Cars].

However, my father’s name could get in the way. For example, when driving for Ford [in 1991], I called Toyota and said, ‘I would like to have a meeting to talk about coming to Toyota next year,’ and they came back to me and said, ‘No. You can’t come to our team to find our secrets and tell them to your father.’ So sometimes it was frustrating.

That year, with Ford, the Sierra Sapphire Cosworth was very unreliable. And I had a new team-mate who nobody knew but he was really, really fast. That was François Delecour. He was so fast on Tarmac, faster than me and Malcolm Wilson, but not on gravel. At the end of the season Ford changed me for Miki [Biasion] and Miki had the same problem with matching François! After winning Group N, the following year, I moved up to Group A and finished third in the championship, and second the following year, in ’89. But that season [’89] was a bad one. It started with the accident at Monte Carlo [Fiorio’s Integrale left the road after a hard landing and killed two people] so once we got to Portugal the feeling for driving was not good. The accident affected me through the season. I was thinking to go fast but I was not going fast. You think you are doing your job as a driver, but there was something deep inside holding me back.

I did another year with Lancia and the Jolly Club and then in 1991 I decided to go to Ford. Why? Well, it’s not good to admit it but to be honest it was about the money. The pay at Lancia was a quarter what I got from Ford.

Also, I knew Ford had a good car. But once I got there I realised that Ford was really slow to respond and make improvements to the car. For example, I remember we had a big problem with the differential in Greece. That was the beginning of June. I had a call from Peter Ashcroft [Ford’s competitions manager] saying a new design of differential wouldn’t be ready until San Remo in September, and he wouldn’t be sending me to any of the rallies until then. Ford had a fast car. I won eight or nine special stages in Greece. The problem between the Italian Lancia team and Ford was that when you won a stage the Italians would give you love and charge you up; when I won nine stages with Ford and got back to the service area they acted like I’d just come in 20th. It was the same atmosphere whether you won or lost. There was no motivation.

At this time my father was very busy with F1, so it was not so easy to talk with him and ask his advice. So I approached the only other factory team in the world championship, Mazda. Achim Warmbold and I talked and in December we agreed to sign a two-year contract together, in January. Then Mazda announced it was pulling out of rallying.

I had always said to myself, ‘I’ll race until I’m not a paid driver. When that happens, I’ll stop driving,’ and that’s what happened. It was the moment to stop.

When I look back and reflect on our family and what we have achieved in motor sport, I feel proud. It was a big scare when Dad had his cycling accident, when he was hit by a car just 7km from here. I’m just pleased that he is now recovered and we can focus our time on the masseria, with all the family helping run it so that he can step back and take things gently.”