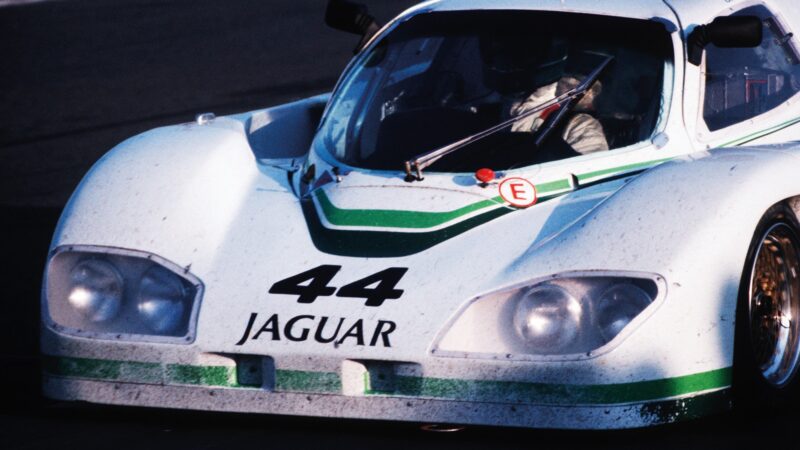

Jaguar's Group C Porsche-killer

From 1976-87 a Porsche had taken the flag at Le Mans on 10 occasions but in the early 1980s Tom Walkinshaw Racing had designs on getting Jaguar back among the winners. Gary Watkins tells the story of a successful British comeback powered by a V12 that had been compared to a fish and chip shop...

When Tony Southgate saw the engine around which he had to design a new Group C car, he did two things: utter a profanity under his breath and reach for a bandsaw. The swearword was a reaction to the size of the V12 lump in front of him, the bandsaw a tool with which to try to pare it down into a form suitable to go into the back of a pure-bred racing prototype. That car was to be a Jaguar, the first of a line of 12-cylinder machines built by Tom Walkinshaw Racing that would go on to win the Le Mans and Daytona 24-hour classics two times apiece, not to mention a pair of world titles.

That’s a pretty decent haul for a car powered by an engine that Southgate describes as “the size of a fish-and-chip shop”. He was no stranger to designing V12 racing cars — he’d penned Formula 1 machinery for BRM, Shadow and Osella with engines of such a configuration — but this one was out of a road car and had first seen service in Jaguar’s Series 3 E-type back in the early 1970s.

There was, Southgate points out, no debate about the choice of engine when he began work at TWR as a freelancer at the back end of 1984.

“Tom Walkinshaw said I could do anything I wanted, and he obviously liked Formula 1-type technology,” explains the British engineer. “But he told me that was the engine we had to use.”

Jaguar XJR-6s, 51 (Warwick/ Cheever) and 52 (Schlesser/ Brancatelli), pitting at the 1986 Silverstone 1000Km

Alamy

Jaguar’s return to motor sport in the early 1980s under the aegis of new boss John Egan was about rebuilding a marque that was still part of the state-owned British Leyland conglomerate. Or, in his words, “putting the company back together”, as well as “making sure there was a glamour associated with the brand”.

“It wasn’t about simply racing, it was about racing with Jaguar components,” says Egan, who was knighted for his services to industry in 1986. “I wouldn’t have gone racing if we’d had to build a special engine. I wanted a very clear connection between Jaguar products and our racing programme.”

Jaguar was already making that connection with twin racing programmes that kicked off in 1982 on either side of the Atlantic. Group 44 was representing the marque in the IMSA GT Championship with a GTP prototype powered by the 24-valve V12, while TWR was fielding the XJS with the same engine in the European Touring Car Championship. These two programmes are intertwined in the tale of Jaguar’s ultimate return to the top step of the podium at Le Mans in 1988.

job done – Johnny Dumfries at Le Mans ’88; co-driver Jan Lammers is behind

AFP via Getty Images

Group 44 boss Bob Tullius had been told by Egan when he was given the go-ahead for the IMSA campaign that he would take the marque back to Le Mans. But he was warned he would eventually lose the programme. Egan had said that “one day we are going do this ourselves from the factory”. Tullius presciently interpreted that comment as more than a hint that the deal would end up going to a British team.

Tullius did take Jaguar back to Le Mans in 1984 with his aluminium-chassis XJR-5. For 1985, there were due to be two teams flying the flag for the marque at the Circuit de la Sarthe: Group 44 and TWR. It was planned that the British operation, which had been developing the V12 for the Group C fuel-formula since mid-1983 at Jaguar’s behest, would field a pair of Tullius cars alongside the US operation.

“It wasn’t about racing, it was about racing with Jaguar components”

That was stipulated in the original Jaguar-TWR deal, but by the time it was signed off in 1985, Southgate was already at work on the new car that became the XJR-6. “You couldn’t really imagine Tom running someone else’s car, could you?” he says.

TWR did test an XJR-5 in the UK on a number of occasions in the early months of ’85, as Southgate progressed the design of its own carbon-chassis car around the V12. In secret and without Jaguar funding.

“I knew the engine was going to dominate the car because of its sheer size and weight,” says Southgate of a power source that in full-dressed form in the XJS topped 300kg, aluminium block or no. “We shoved it as far forward as possible with a recess in the fuel tank so it was almost right behind the driver’s shoulders. Then we shunted the rear wheels back with a big bellhousing to make a long wheelbase to try to get a decent weight distribution.”

Frying tonight: this is what a 6-litre V12 looks like, Le Mans, 1986

GPLibrary via Getty Images

XJR-9 at Daytona the same year

ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images

Group 44’s 1985 XJR-5

Alamy

There were advantages to the V12, however. An engine with a 60-degree vee angle was tall and therefore top heavy, but it was also narrow in shorn down form. That allowed Southgate to go to town on the aerodynamics, something he considered to be one of the weak points of Porsche’s all-conquering 956/962 Group C design powered by a flat-six turbo engine.

“We made the engine narrow so we could run ruddy big [ground-effect] tunnels down the side,” he explains. “There was a big flange for the bellhousing that was part of the block, so I bandsawed that off. The starter motor was on the side and we moved that to the front to get it clear of the tunnels.”

“Maxing out the downforce” was Southgate’s mantra in the design of the XJR-6. There was no frame around the engine: it ran as a stressed member, the loads taken through the sump and the cam covers, with only a couple of stay bars for support. The uprights and spring damper units at the rear were enclosed within the wheels. “I stuffed everything inside the wheel, which meant the tunnels could go right up to the inside of the tyres,” he says.

The TWR design team, with Kiwi Allan Scott heading up engine development, also got the V12 as low as possible. Southgate talks about the sump being little more than a flat plate. Charlie Bamber, a long-time member of the TWR engine department, reckons, “It did have a bit of depth to it — but I wouldn’t say more than an inch.”

The Dumfries/Lammers/ Wallace XJR-9 LM heading for victory at Le Mans ’88, ending Porsche’s seven- year winning streak

Pascal Rondeau/Getty Images

The XJR-6 might have ended up with an even heavier version of the V12. TWR’s toe into the sports car waters with Jaguar had on development a four-valve head for the V12. It was this engine that sat in the back of the XJR-5 TWR tested early in ’85. This was based on a casting produced by Jaguar as a design study, which Bamber remembers as “not being fit for purpose”. It was abandoned as the first XJR-6 started to come together in the summer of 1985. The idea of going to Le Mans — with either the 5 or the 6 — had been abandoned and the bespoke TWR car was given a race debut at the Mosport round of the World Endurance Championship in August.

One of the two cars entered in Canada led on its debut, the other finished a delayed third, limping home on 11 cylinders. At the end of the year, Jan Lammers, John Nielsen and Mike Thackwell finished second and on the same lap as the winning factory Porsche 962C at the Shah Alam circuit in Malaysia. Jaguar had to wait only two more races to record its first world championship sports car victory since 1957 in the second round of the renamed World Sports-Prototype Championship in 1986. Derek Warwick and Eddie Cheever triumphed on home ground for the marque in the Silverstone 1000Kms, now with the XJR-6s running in the colours of Silk Cut cigarettes.

Jaguar didn’t win again that year, though it did lead multiple races. Warwick took another four podiums over the season and was briefly declared champion. He was initially classified second with Cheever at the finale at Fuji, but when a timing error was discovered they were demoted to third. That pushed the Briton down in the points table behind Porsche factory drivers Derek Bell – who ended up as champion courtesy of a bizarre tie-break rule – and Hans Stuck.

Jaguar took both drivers’ and teams’ titles the following year. Brazilian Raul Boesel was crowned champion ahead of a trio of other TWR drivers as the Jaguar XJR-8, an evolution of the 6, won all but two of the 10 races. It is only a matter of record that the Porsche factory team wasn’t present after the summer as its focus turned to CART single-seaters in North America.

The XJR-6 recorded a single win in the 1986 WSPC; flat-six Porsches accounted for seven

DPPI

One of the two races Jaguar didn’t win was the big one at Le Mans. It put that right the following year with an XJR-9 driven by Jan Lammers, Andy Wallace and Johnny Dumfries. Less than six months earlier a Jag had won at Daytona on the debut of a new TWR North American operation. Martin Brundle gave the team a second world title as the Jags won six of the 11 races. There was another 24-hour double in 1990, too, Brundle, John Nielsen and Price Cobb claiming the victory laurels at Le Mans.

All these successes were achieved with an ageing engine boasting only two valves per cylinder, one that increased in capacity from 6.2 litres to 7.4 over the life of the TWR Jaguar programme. That was the beauty of Group C. The rules were designed to be inclusive, to encourage multiple makers by limiting performance with a fuel allowance that stood at 510 litres for every 1000km in the distance races and at 2550 litres at Le Mans by the time TWR arrived in 1985.

“We got some very good power figures for a two-valve engine and the brake specific fuel consumption of any well-tuned engine should be similar,” says Bamber. “With 12 cylinders we also have the capability to run the engine very lean. If you have two engines with 600bhp, a six-cylinder and a 12-cylinder, one of those you are going to be able to run leaner without damaging it. And that’s the one with the most cylinders.”

There was another dabble with a 48-valve head for the V12, a ‘Jaguar’ turbo developed out of the Metro 6R4 rally engine arrived in 1989 and then the 3.5-litre Group C rulebook resulted in the XJR-14 powered by a re-badged Cosworth HB engine in ’91. But TWR’s weapon of choice for the enduros always remained that hulking great V12.