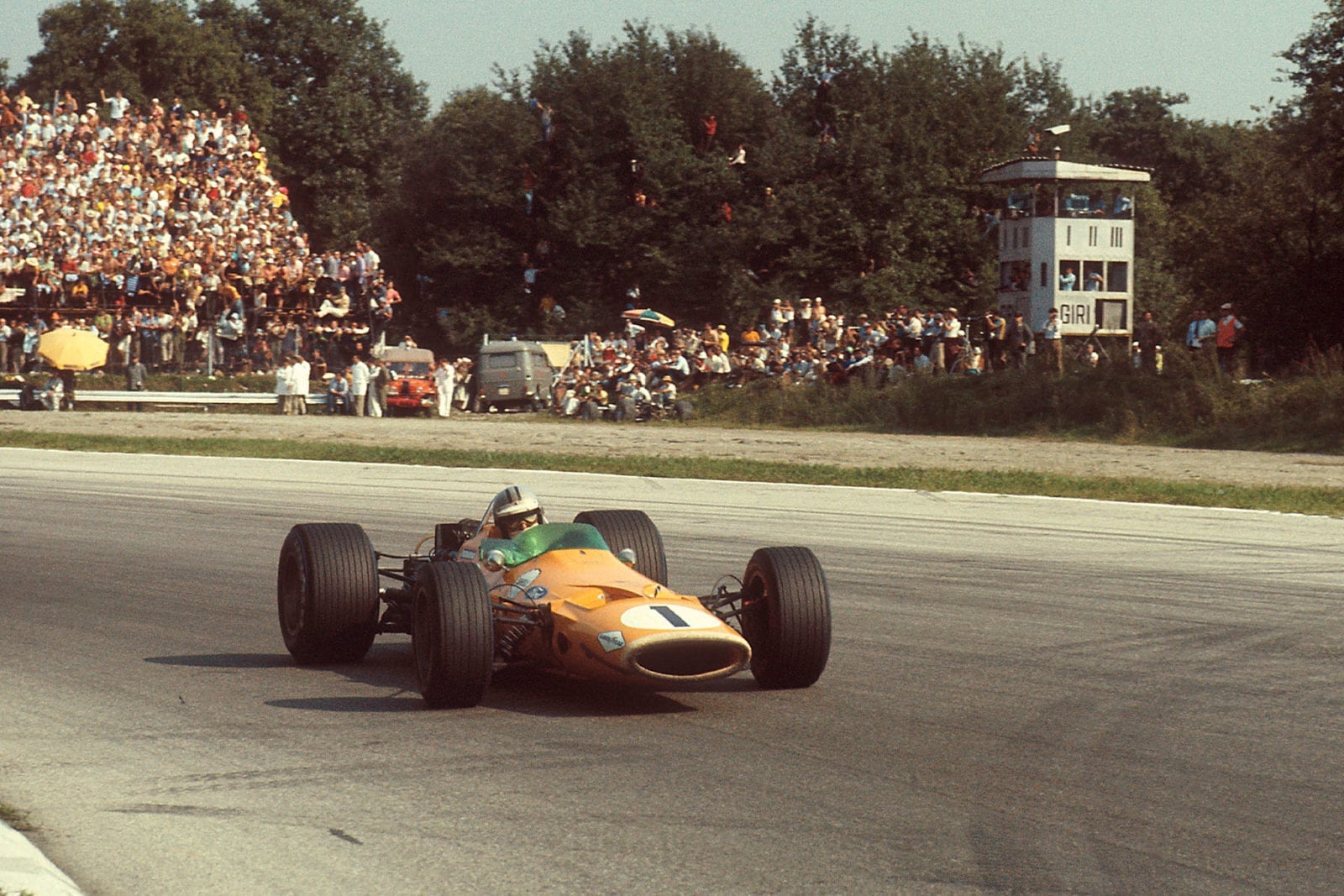

1968 Italian Grand Prix race report: Kiwis' sweet victory

Denny Hulme takes McLaren’s second ever victory; Servoz-Gavin wins-out in photo finish with Jacky Ickx

Hulme won his first race of the season

Motorsport Images

The mere mention of Monza conjures up speed and Grand Prix racing with no ifs or buts, and once again the Italian track lived up to its reputation. Although practice did not start officially until 3pm on Friday afternoon, the track was a hive of activity nearly all week, with teams trying out new cars and new drivers, and there was no doubt that the 1968 race was going to be a hard and very fast event.

The entry was one of the best seen in Grand Prix racing for quite a time, with Lotus, Ferrari, Matra and Cooper all entering three-car teams, and Honda entering two cars. The two USAC drivers, Andretti and Unser, were signed up to join in Grand Prix racing, the former with the third Team Lotus car, and the latter with the second BRM, taking the place of Attwood, who was dropped from the Bourne team without any warning.

The two Americans practised extensively before official practice began, and Andretti showed excellent form, lapping faster than the existing lap record, so that it was clear that the regular Grand Prix drivers were going to set some searing speeds during practice.

“If the two USAC drivers returned to America to take part in the Hoosier 100 race before the Grand Prix, they would be disqualified”

With a total of 26 entries, someone was going to get left out, for the regulations specified that only 20 cars would start the race, these being the fastest 20 during the two afternoons of practice. Before it all began there were some non-starters, two of the Cooper entries being withdrawn as Widdows had had an accident testing a prototype car for the Gulf JW team, and Alfa Romeo would not allow their 3-litre V8 engine to be raced, so Bianchi’s entry was withdrawn.

In addition, the organisers made it clear that if the two USAC drivers returned to America to take part in the Hoosier 100 race on the Saturday before the Grand Prix, they would be disqualified, for the rules forbade any driver to take part in two events within a time span of 24 hours.

Andretti was disqualified before he could race

Motorsport Images

After doing the minimum of practice on Friday afternoon, both Andretti and Unser flew to America to take part in the USAC Championship event, and though there was much lobbying before race day, the Italian Federation stuck to their rules and disqualified both drivers. All this left 22 cars to qualify for the 20 places on the starting grid, and as the Bernard White BRM V12 had all the wrong gear ratios, it was unlikely that Gardner would qualify the car, and with so much factory activity Moser had little chance of qualifying, so that the outcome was pretty cut-and-dried.

What was not so sure was the order which the 20 runners would occupy on the grid, for unofficial practice had shown that no one had a monopoly on speed, and practice got under way with a rush when Andretti and Unser roared away from the pits to get in some official laps before flying away, just in case the rules were bent for their benefit.

The McLaren team had three cars, the number 3 car being kept as a spare, and both McLaren and Hulme were having second thoughts about nose fins and aerofoils, trying experiments with and without them. The Ken Tyrrell Matra International team had completely rebuilt their first MS10 car, for Stewart to race, and had prepared the second car, which won the German GP, for Servoz-Gavin to drive.

Beltoise drove the V12 Matra, as in Germany, with the electrically operated aerofoil. Ferrari produced four cars in all, numbers 0007, 0009, 0011 and 0015, ringing the changes on them for the three works drivers, Amon, Ickx and Bell.

All four cars were fitted with movable aerofoils, controlled electro-hydraulically either automatically from the brakes and gear lever, or manually by the driver. The system is described elsewhere in this issue. The two works Brabhams appeared with an aerofoil mounted high above the nose and a bigger one across the tail of the car, the rear one being adjustable by cable from the cockpit.

On Rindt’s car the control lever was not calibrated, it being left to him to play with the mechanism. On Brabham’s car there was an indicator mechanism to allow him to take readings of the effect of the aerofoil movements, the idea being that when the optimum had been found by him, this setting could be applied to Rindt’s car.

Honda Racing were out in force, Surtees having the V12 car he has been racing all season, as well as a brand new air-cooled V8 car, more or less identical to the ill-fated Rouen car, while Hobbs had a brand new V12 car to the same design as the earlier V12, but tidied up in small ways as a result of the racing done by Surtees. The new V8 car did not appear for the first practice, as it had developed some serious oil leaks during unofficial practice.

Gold Leaf Team Lotus had rebuilt the car that Oliver crashed at Rouen, it all being virtually brand new but retaining the number 49B/6, and the other two cars were 49B/2 and 49B/5, and all three were fitted with redesigned radiator nose cowlings, in which air from the radiator exited upwards through two large openings on the top of the cowling, like the McLaren cars. These new nose pieces were split horizontally, the lower part carrying the nose fins, and the upper part fitting over the radiator and pedal assembly.

The works Lotus 49B cars were supported by the Walker-Durlacher car, driven as usual by Siffert. With the exception of this last car, all the Cosworth V8 engines in McLaren, Matra and Lotus had new exhaust systems in which the four pipes from each bank of cylinders joined in a group into the tail pipe, instead of two pipes into two, and the two into a tail pipe. This new system, together with other improvements in the engines, produced another 15bhp at 9,900rpm, instead of the previous 9,500rpm, albeit at the expense of some loss of power lower down the curve, but at Monza this was not important, maximum output being all-important on the Italian track.

Gurney was driving his lone Eagle V12, and Elford was the only Cooper driver, having two works cars to choose from. The first Cooper had a movable aerofoil designed in co-operation with Vickers, in which the aerofoil was pressed down into the horizontal position by the air pressure at maximum speed, two small levers compressing coil springs so that as the speed dropped the aerofoil moved back into the maximum down-thrust position; a very simple and effective mechanism.

The BRM team produced a brand-new car designated the type P138, though it did not run in the first practice. The main change in this car being the fitting of a 5-speed BRM-built gearbox in place of the Hewland gearboxes used on the P126 and P133 cars. The rear of the monocoque was improved, being extended beyond the rear bulkhead, to carry the suspension mountings, instead of having a tubular structure bolted on to the bulkhead. Rodriguez and Unser used the earlier team cars during the first practice, while Courage drove Parnell’s P126 BRM V12.

Qualifying

Pole-sitter Surtees pulls into the Honda pits

Motorsport Images

Once the two USAC drivers had flown away, practice settled down to the serious business of sorting out the starting grid, and Amon was upholding Ferrari honours with great efforts, each fastest lap being loudly acclaimed by the crowds of spectators. Surtees was making serious progress with the V12 Honda, and was challenging the Ferrari times, much to everyone’s joy, for Surtees is still extremely popular with the Italian crowds.

“Surtees got down to a shattering 1min 26.1sec, actually showing immense pleasure at the way the Honda V12 was going at last”

After Andretti’s car had been put away there was a depressing lack of works Lotus cars, and it was quite late in the afternoon before Oliver appeared, his car not being complete when it arrived, while Hill appeared even later, his gearbox having broken the day before. All the Team Lotus efforts had gone into preparing Andretti’s car so that he could get going the moment the track was open for official practice, and this had withdrawn some of the effort from the other two works cars.

The existing lap record stood at 1min 28.5sec, set up last year by Jim Clark in a Lotus 49, and this figure took a severe beating, showing just how much progress the Grand Prix designers had made in 12 months. All the top works drivers were well under this figure, and Surtees got down to a shattering 1min 26.1sec, actually showing immense pleasure at the way the Honda V12 was going at last.

With very little practice, Hill got down to 1min 26.57sec, which gave him second place, and Hulme, Ickx and Amon were so close that lap-time readings to 1/100th of second were needed to separate them. The accompanying list of practice times shows that 13 drivers got below the lap record, while others were very close. Gurney was most unhappy, as his Eagle V12 engine, which had performed very well on the test-bed with megaphone exhausts, just would not run properly with the megaphone system on the car.

Most of the “old hands” did the sort of lap times expected from them, but there were also some good times from newcomers, notably Derek Bell with the third works Ferrari, Servoz-Gavin with the Matra-Cosworth V8, Hobbs with the brand-new Honda V12, and Siffert with the Team Walker Lotus 49B.

In the brief practice that he did, Andretti made a very representative time of 1min 27.20sec, but Unser was not even as fast as Courage, and did not break 1min 30sec. Stewart did a few laps in Servoz-Gavin’s car and recorded a time only one-tenth of a second slower than he had done in his own car, which illustrated a fine degree of meticulous preparation by the Tyrrell team.

For a change the weather conditions were superb, and the blazing sunshine and blue skies continued during Saturday, when practice was once again from 3pm to 6:30pm, nobody having any complaints about lack of practice time.

The Ferrari team were still juggling about with their four cars and three drivers, quite often two cars having the same number, and others were juggling about with aerofoils and fins, as there was a growing feeling that the increased drag of the various layouts was a greater handicap than the increased cornering power was an advantage.

Elford had the two works Coopers to experiment with, the number 1 car, labelled 22T, with the movable aerofoil, and the number 4 car, labelled 22, without an aerofoil. Having forgotten his driving boots, he borrowed some others and had not done many laps before he got his right foot caught up in the pedals and overshot the braking point going into the South Curve, and crashed into the barriers, wrecking the left rear corner of the number 4 Cooper.

It was not his day, or Cooper’s for that matter, for later he went out in the number 1 car and the BRM engine blew up expensively, so Cooper were left with one wrecked car with a good engine and one good car with a wrecked engine.

In view of the general high speed that all the top drivers were producing, Elford was outclassed and looked like only just scraping into the starting list, providing the mechanics could build one car out of the two. Siffert was trying the Walker/Durlacher Lotus without fins and aerofoil, and had reached the stage where he was going to make the final decision as to whether to use them or not by tossing a coin!

Stewart’s Matra-Cosworth had its rear aerofoil remounted, on tubular struts from each end to the suspension uprights, while the other Tyrrell car retained the original layout, with the aerofoil mounted on the chassis frame.

The Brabham team were in trouble with broken engines, and Rindt did a lot of practice in the spare car, but for a change the Honda team seemed very organised, the two V12-engined cars going well and Surtees smiling happily at his car’s performance. There was even time to do a few exploratory laps in the brand-new V8 air-cooled Honda, most of the joints of the engine being covered with horrid-looking “jollop” to try and keep the oil inside.

With the first day’s practice giving a good indication of the expected pace for the race, fuel consumption was going to be pretty critical and the V12 Matra had extra tanks on each side of the cockpit, the V8 Matras had scuttle tanks and bulging cowlings in front of the cockpit, and the McLaren team were making up extra fuel tanks to fit on the side of the cockpits.

The Ferrari team were doing consumption tests as well as trying to get their cars up with the Honda and Lotus. Running with the minimum weight of fuel on board to try for better lap times, both Amon and Bell ran out of fuel, the New Zealander on the far side of the circuit, so that he had to be rescued, while the English driver was able to coast to within sight of the pits.

The BRM team seemed to be in a right old shambles, having suffered numerable engine breakages, and arrived very late for this last practice period, producing the new P138 car, but it was not in the running as far as speed was concerned. Whatever features are desirable at other circuits, Monza demands speed and yet more speed, and this is dependent on sheer horsepower, none of the corners calling for any sophisticated power curves or middle-range torque figures.

“The BRM team seemed to be in a right old shambles”

Gurney was getting more and more depressed at the poor performance of his Eagle, perhaps feeling the loss of the Weslake influence on the V12 engine, and came to an arrangement to borrow the spare McLaren-Cosworth, but it was too late in the day and the organisation would not accept a change of car.

Obviously they preferred an Eagle on the starting line to a third McLaren. With various people trying the effect of no nose fins or aerofoils, and the McLaren team deciding to run “naked”, even Ferrari had second thoughts and they stripped all the “gizmos” off 0007 and let Amon try it, but settled for the original layout, with movable aerofoil.

Ickx came in to complain that his aerofoil did not seem to be doing the right things at the right time, and also that the pressure warning light for the system was coming on at the wrong time, but the engineers felt that he was getting muddled in operating the controls.

However, both Ickx and Amon had beaten the best Lotus time, but Surtees was still fastest with his 1min 26.10sec from Friday. Then he took the Honda out again and got involved with two McLarens and while using Hulme’s slipstream and pulling out and overtaking at the crucial moment, he got in a lap at 1min 26.07sec, leaving the McLarens to get involved with a great crowd of cars that developed into a last-minute flurry that made it look as though the race itself had started.

There were six or seven cars in a bunch, all nipping in and out of the slipstreams, trying to judge the right moment to improve the lap time. In the midst of it all there was a puff of blue smoke and Oliver’s Cosworth engine blew up. As the chequered flag was being got ready to announce the end of practice McLaren timed his movements right and recorded 1min 26.11sec, to give him second fastest overall. As Hill crossed the line at the end of practice his engine cut out completely and he coasted out of sight in complete silence, the fuel-metering unit drive having sheared.

It was a good thing the race was not due to start until 3:30pm on Sunday, for the mechanics had a lot of work to do, with Lotus, Cooper, BRM and Brabham having blown-up engines, and also Parnell’s BRM, while Ferrari were not happy about the engine in Bell’s car.

Spare engines were getting short, for while everyone expected Monza to be a bit of a thrash, no one anticipated quite so much trouble. Lotus were reduced to only one serviceable car, that being Andretti’s number 18, and as there was little hope of a change of decision by the organisers, the Team Lotus mechanics started work, putting all Oliver’s bits and pieces on it, such as spring and shock-absorber settings, anti-roll bars and so on.

Hill’s car had another engine installed, and the blown-up Oliver practice car was put on the transporter and forgotten. Cooper put the engine from the crashed car into F1-1-68 for Elford and removed the aerofoil, and the Brabham team had so many other troubles to attend to that they had long since abandoned all experiments on the double aerofoil layout, reverting to the nose fins and small low-mounted aerofoil over the rear of the car.

“Spare engines were getting short, for while everyone expected Monza to be a bit of a thrash, no one anticipated quite so much trouble”

Both Brabham and Rindt were using their original BT26 cars, the latest one being left in the paddock. McLaren and Hulme were also back to the cars they had at the beginning of the season, and had seven-gallon fuel tanks strapped on the right side of the cockpit, an electric pump transferring the petrol to the main system when required.

The two Matra-Cosworth cars were using nose fins and high aerofoils, Stewart having the suspension-mounted one and Servoz-Gavin the chassis-mounted one, while the Team Lotus cars had never at any time shown signs of removing any of their aerodynamic assistance. However, Siffert decided to run “naked” like the McLarens, but all three Ferraris were in full aerodynamic order.

Rodriguez had the suspension-mounted aerofoil on the new BRM, and Courage had a similar layout on the Parnell car, it having the engine from a spare works car to replace the one blown up at the end of Saturday’s practice. The two V12 Hondas were also carrying rear-hub mounted aerofoils.

Race

Wheels smoke as the cars pull away

Motorsport Images

Saturday night had seen rain falling, but by midday on Sunday all was set fair and the temperature was typical Monza, with the sun blazing down on the vast crowd, estimated at over 90,000, and certainly the grandstands were overflowing and the car parks full, while there were signs of cars being abandoned well outside the Park entrances.

Just after lunch-time the two American drivers arrived back, but they were to be spectators, for there was not a Lotus for Andretti and Unser hadn’t qualified anyway, but apart from this the organisers refused to revoke the original decision.

The 20 cars came out of the paddock in a rather untidy and disorganised fashion, and assembled on the “dummy-grid” and much more care was taken with the waving of flags when the time came to move forward to the proper grid, in order to avoid a repetition of last year’s running-start.

Everyone was on full-song and there was terrific tension in the air, for one could sense that this was going to be one of the fiercest and fastest Monza races ever witnessed, and when the Italian flag was dropped to start the field on the first of the 68 laps, all 20 cars surged away splendidly.

From the front row the Honda leapt away, with the McLaren right alongside, but the Ferrari began to pour smoke from its rear wheels as Amon gave too much throttle. As they changed into second gear McLaren got the lead from Surtees and then the whole lot were gone from sight.

“There was virtually no break as the 20 cars roared by”

At the, end of the first lap it was McLaren leading with the whole boiling mob right behind him, and there was virtually no break as the 20 cars roared by. On the second lap the situation was the same, with Hill, Surtees, Amon, Stewart, Hulme, Ickx, Oliver and Rindt following McLaren as quickly as you could say the names.

On lap 3 there was a shuffle and the order read McLaren, Stewart, Surtees, Hill, Amon, Siffert, Hulme, etc, but only 18 cars went by. A cloud of dust rising from the Parabolic South Curve indicated where Elford had once more gone straight on under braking and out of the race, and Rodriguez was in the pits with throttle linkage derangements.

Next time round the Honda had moved into second place behind the McLaren, and it was followed by Amon’s Ferrari, and Hill’s Lotus, Stewart being down in fifth place, but as the first nine cars were almost touching one another, first place or fifth place was purely academic at this stage.

On lap 5 Bell went missing, his Ferrari engine dying on him soon after passing the grandstands and pits, the cessation of power being attributed to something amiss in the fuel-feed system. Siffert had moved up a place and on lap 6 he moved up another place, now being fourth, while the tail-enders began to fall back. Surtees led at the end of lap 7, followed by McLaren, Amon, Siffert, Hill, Stewart, Hulme, and Oliver, and this leading bunch were now breaking away from the rest of the runners.

Ickx, Servoz-Gavin and Rindt were in close company, then came Gurney and Hobbs, the latter going well on his first serious Grand Prix outing with a competitive car, and bringing up the rear were Brabham (very unhappy with a poor engine), Courage, Beltoise and Bonnier.

On lap 8 there was some more chopping and changing among the leaders, and McLaren went ahead again, Amon tucking in behind him and relegating Surtees to third place, while Stewart moved up ahead of Hill, the rest following as before.

Half-way round the ninth lap there was general panic, for Amon overdid things in the Lesmo corners and spun, and while doing so Surtees had to take avoiding action and struck the guard-rails. The Ferrari crashed over the iron rails and the Honda wrecked itself, luckily neither driver being hurt, but those immediately behind had some exciting moments, and Oliver managed to spin and drop three places.

Gurney leads Bell and Servoz-Gavin

Motorsport Images

Before this unfortunate incident Oliver had been credited with fastest lap and a new record, in 1min 26.5sec, on lap 7, but the seven cars in front of him could not have been more than a one-hundredth of a second slower, for the whole lot were running nose-to-tail.

The Amon/Surtees accident allowed McLaren to get a measurable lead, but Stewart and Siffert were after him again, followed by Hill and Hulme, but then there was quite a gap before lckx, Servoz-Gavin and Rindt came by. Rodriguez was mixed up in the main pack of cars, but a whole lap behind, due to his pit stop, and the new BRM was not proving to be very fast.

“Hill subsided in a cloud of dust when a rear wheel broke off at the hub centre, and he skated to rest and out of the race”

On lap 11 Hill subsided in a cloud of dust when a rear wheel broke off at the hub centre, and he skated to rest and out of the race, and the scene showed signs of settling down. The leading group now comprised McLaren, Siffert, Stewart and Hulme, their cars all powered by Cosworth V8 engines, and then came Servoz-Gavin, lckx and Rindt, so that Cosworth engines were in the first five cars. Oliver was ninth, on his own, ahead of Hobbs, Gurney, Courage and Brabham, while Beltoise and Bonnier brought up the rear.

The leading quartet were not settling for any particular order, passing and re-passing as often as they could, while the average speed was rising all the time, being well over 230kph (approx 143mph) and less than one second covered them. McLaren led, then Stewart led, then Siffert, then Stewart and Siffert side-by-side for a couple of laps, and then Hulme led.

A similar scrap was going on between Ickx and Servoz-Gavin, with Rindt ever in their slipstream, and behind them Gurney and Brabham were being harassed by the new boys, Hobbs and Courage.

By lap 16 Bonnier had been lapped, and the battle for the lead still raged, with Siffert pulling out of Stewart’s slipstream as they crossed the timing line. It was lap 19 when Hulme took the lead, and though the other three were all round him at times, he managed to end each lap in the lead until the 27th lap. Gurney’s Eagle expired in a haze of blue smoke as he coasted into the pits at the end of the 20th lap, and three laps later Rodriguez came into the pits with the new BRM blown-up.

On lap 22 McLaren got in behind Hulme, and managed to stay there, with Stewart and Siffert close behind, and the two New Zealanders tried all they could to help each ether, but they were up against a couple of slippery customers, and they could not make any team tactics pay off.

Just when it looked as though stalemate had arrived, with the two McLarens leading but unable to get away, the whole position was shaken up again and McLaren was in fourth place and Stewart was in the lead, but it was only for one lap, and then Hulme was back in front.

However, all was not well with McLaren and he began to lose contact with the leader, and on lap 30, when Stewart had another go in the lead, Hulme had no one to help him, for McLaren was dropping back visibly. Behind them the Ickx, Servoz-Gavin, Rindt trio were still hard at it and still changing places, Rindt at last getting between his two rivals as they were about to lap Beltoise in the V12 Matra.

Hulme was still swapping the lead with Stewart, and Siffert was never more than a few lengths away, his lower-powered Cosworth engine being unable to challenge the two works cars, but it was able to stay in their slipstreams.

On lap 34 McLaren pulled into the pits with oil coming out of the front of the engine from a hole where a bolt had come undone and fallen out, and though he did one more lap to make sure, his race was over. On the same lap Rindt had coasted into the pits with a blown-up engine, a cloud of blue smoke at the exit of the Parabolic Curve showing where the Repco engine had gone bang.

With these two out the pattern of the race changed, for Hulme now began to dominate the lead, even though he could not shake Stewart and Siffert from his slipstream, and Ickx was now getting away from Servoz-Gavin. When Rindt had got between them he had forced the Matra out of the Ferrari’s slipstream, and when they lapped the V12 Matra, Beltoise nipped in behind his fellow Frenchman and got a suck from the slipstream, but this had the effect of slowing the Cosworth-powered car.

With the exception of the 40th lap Hulme now led all the way, but it was still a precarious lead and only 1.1sec covered the first three cars, and the average speed had risen to 233.2kph Ickx and Servoz-Gavin were the only two not lapped by the leaders, Hobbs, Courage and Brabham all having succumbed and were a lap down, while Beltoise and Bonnier were much farther back.

Suddenly, and without any warning, Stewart’s Cosworth engine blew up and he coasted into the pits in a smoke haze; hardly had this happened than Hobbs’ Honda broke its engine and he came into the pits with steam rising and water coming out of places where there should not have been any water.

“Ickx moved into third place and the vast Italian crowd came to life with a great scream of delight”

All this left Hulme and Siffert out on their own, the Swiss driver doing all he knew to stay with the World Champion, but his Lotus did not have the same speed and he could do no more than keep in the draught of the McLaren.

With Stewart going out Ickx moved into third place and the vast Italian crowd came to life with a great scream of delight, for third place was important, fourth was not. With a Ferrari in third place there was renewed hope, for Ickx could possibly catch Siffert, and with two Cosworth-engined cars already fallen by the wayside, who knew when the next one would go, and then there was every chance of a Ferrari victory. Ickx was encouraged on all sides and he drove faster and faster, gaining slowly but surely. Meanwhile, Hulme was pulling away from Siffert.

At 50 laps, with 18 still to go, the race average had risen to 234kph and Hulme led by 5.8sec, with Ickx 39.4sec behind. By one second and sometimes two seconds per lap the Ferrari was closing the gap, and now that Siffert had lost the suck from the McLaren he was helpless to fight off the challenge of the young Belgian driver.

At 57 laps Hulme led by 9sec and Ickx was only 21sec from the Lotus, and at that point Brabham retired, having been watching his oil pressure get lower and lower, stopping before the Repco engine broke.

As Hulme ended his 59th lap the grandstands rocked with excitement, for Siffert was heading for the pits, which meant that Ickx was now heading for second place, and a Ferrari in second place meant that a Ferrari could well win the Italian Grand Prix.

As Siffert had braked for the South Turn the bottom mounting eye of a rear spring/shock-absorber unit had broken off and he stopped with the lower wishbone hammering on the end of the spring unit. Nothing could be done and his race was over, his fine drive being applauded loudly by the enthusiastic crowd.

However, next time round panic broke out in the stands, for the Ferrari was no longer running so strongly, showing signs of fuel starvation, and feeling that he might be running low on fuel Ickx weaved the car along the straight to slop the petrol around in the tanks. He was not running out of petrol, but the temperature was causing vapour locking and his main fuel pressure was dropping, affecting the injection system.

By this time Hulme had lapped Servoz-Gavin, who was in third place. On lap 61 there were screams of anguish as the Ferrari was seen to be heading for the pits, where some fresh petrol was poured into the tanks, hoping that it would lower the overall temperature and cure the vaporising.

As the Ferrari accelerated along the pit lane at a furious pace the blue Matra of Servoz-Gavin went by to the accompaniment of “Press-on” signals from the Tyrrell pits. The Frenchman responded magnificently, passing Hulme who had eased off now that all danger was past, so that at the end of lap 62 the McLaren was between the Matra and the Ferrari, the French car being on the same lap as the leader, but almost a lap behind, and the Italian car being one lap and a few lengths behind the McLaren.

Providing nothing untoward occurred Hulme had the race won, and his Cosworth engine was purring along as sweet as could be, so he was happy to ease off and let Ickx go by and have a clear track in his pursuit of the Matra. With all the retirements Courage was now in fourth place, having been driving since the start with an inoperative clutch, the pedal movement not freeing it at all, but nonetheless enjoying himself and doing full justice to the borrowed works engine.

As the Ferrari got closer and closer to the Matra the noise all round the circuit increased and on lap 64 Ickx was back in second place and a blind man would have known immediately. But it was not over yet, for Serzoz-Gavin had no intention of giving up and he had the Matra right in behind the Ferrari, with Hulme just behind and keeping out of the way.

As the red car and the blue car finished their 67th lap, with one more to go, all eyes were on them, and hardly anyone noticed that Hulme had received the chequered flag as he followed them along the pits straight!

“As the Ferrari got closer and closer to the Matra the noise all round the circuit increased”

Through the Lesmo corners the Matra got in front and the commentator nearly burst his microphone, but down the back straight the Ferrari was ahead again, and then everyone was peering down to the South Curve, the last corner in the race for second place.

Hulme was meanwhile doing his slowing-down lap after winning the Italian Grand Prix, but nobody was very interested, it was the outcome of second place that held everyone’s interest. Once again the noise and the clamour made it clear who was leading out of the South Curve and Ickx brought the Ferrari up the straight on his usual line, over to the left by the grandstands.

A victorious Hulme holds the trophy aloft

Motorsport Images

Meanwhile, Servoz-Gavin was taking a more central line, and was a few lengths behind, but with his eyes glued on the Ferrari. Within sight of the flag the Ferrari engine hesitated in its power output, as vapour got into the injection system again, and the rate of acceleration eased off.

This was all Servoz-Gavin needed. He flung the Matra across into the slipstream of the Ferrari to gain every extra mile-per-hour and then whipped out and crossed the finishing line ahead by the merest fraction of a second. It was such a smooth, fast and deliberate manœuvre that thousands of Italians were still cheering Ickx for being second before they realised that Servoz-Gavin had relegated him to third place right on the finishing line.

The tumult was fantastic and through it all one had to remember that Hulme had won the race after fighting a splendid battle throughout the opening stages, and having dominated it for more than half the distance. Monza had once again lived up to its reputation of providing one of the fastest and most furious races of the season.